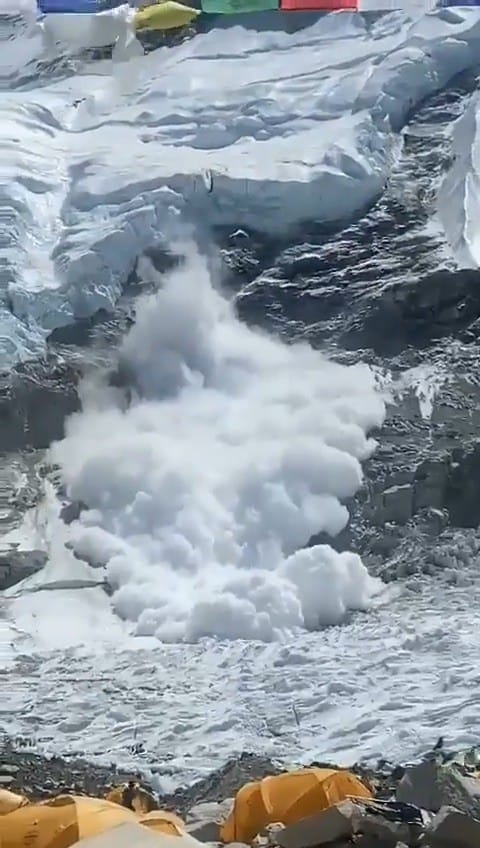

Debris from an apparent serac release off Everest’s west shoulder has taken the lives of three Sherpas in the Khumbu Icefall. They were part of the rope team ferrying gear to begin fixing the route from Camp 2 to the summit. Searchers are said to have located their bodies but have not recovered them, but early information is often wrong.

Massive ice blocks frozen to steep rock walls randomly release every season. To the climber’s left, when climbing from Everest Base Camp to Camp 1, several seracs teeter and regularly fall onto the Khumbu Icefall. In 2013, Russell Brice of Himalayan Experience, aka Himex, canceled his entire expedition based on fears of falling debris on the Icefall. he said at that time,

“I am no longer prepared to take that risk. Of course, there is the possibility that many other teams will reach the summit this season but we at Himalayan Experience are very concerned that a major accident could happen if we carry on moving through the icefall.”

It never happened that year, but in 2014, sixteen Sherpas died when a release did occur. They were ferrying gear to establish camps in the Western Cwm.

Climbers generally pass through the Icefall in the early morning hours when the ice is stable due to the coldest temperatures of the day. The highest danger occurs in the afternoon when the sun hits the seracs. However, the 2014 collapse occurred on April 18, 2024, at 6:35 am.

Deaths from avalanches and melting ice have increased in recent years. This week, near Chamonix, France, six skiers were killed in an avalanche from the Armancette glacier. There have been eleven fatal accidents in Austria, Switzerland & Italy this winter. According to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, over the last 10 winters, an average of 27 people died in avalanches each winter in the United States. There have already been ten deaths from avalanches in Colorado this winter.

Body Recovery

This incident occurred relatively late in the morning at 9:30 am local time at approximately 19,000 feet/5800 meters. Still, as best I can tell, searchers have located the area of missing Sherpas, and they were not swept into a deep crevasse in the Icefall. Early reports from Sherpas, climbers, plus officials and media, are not optimistic their bodies can be recovered. Keep in mind that early information during these tragic events is often wrong

The lost have been identified as Tenjing Sherpa, Lakpa Sherpa, and Badure Sherpa. All worked for Imagine Nepal, which has the role of fixing the upper mountain with fixed ropes.

This section of the route will have to be rebuilt by the Icefall Doctors, so teams will pause climbing for a couple of days. They may reroute ladders to move further away from the West Shoulder to reduce but not eliminate a repeat this season.

The Ministry of Tourism had approved using helicopters to ferry the massive amount of rope, ice screws, pickets and other gear needed to fix the upper mounting to reduce exactly what happened today. Sherpas carrying these heavy loads move slower, thus increasing their exposure to a release occurs. It’s unclear why helicopters are not being used this season, but local authorities had delayed using helis above Syangboche, citing unnecessary traffic.

My condolences to all the families of these brave men.

With this incident, let’s take a deep look at the Icefall and why it’s so dangerous.

A River of Ice that Is Melting

Everything starts with the Khumbu Glacier, a 10-mile/17km river of ice that begins high on the Lhotse Face around 25,000’/7,600m. The Khumbu Icefall is the section between Everest Base Camp, 17,300’/5270m and just below where Camp 1 is usually located, 19,500’/5943m.

Once it leaves Lhotse, the glacier defines the Western Cwm for about 2 miles before dropping rapidly to create the Khumbu Icefall for 2.5 miles. Around Everest Base Camp (EBC), the glacier makes a sharp southernly bend and continues another 6 miles/9.6km to 16,000’/4,900m. The Icefall varies in width from over half a mile/800m to a third of a mile/500m.

As with all glaciers, the Khumbu moves. This one as much as 3’/1m a day in the center while barely moving at the edges due to friction against rock walls. The top of the glacier moves faster than the bottom due to friction against the earth. It is this dynamic of fast and slow-moving sections plus the precipitous drop that create the deep crevasses, some over 150’/45m deep and towering ice seracs over 30’/9m high.

Melting

According to the Kathmandu-based mountain research institute, ICIMOD, the Khumbu Glacier is melting but not as fast as many other glaciers due to its altitude. It is the highest glacier on Earth. It is estimated to be retreating about 65’/20m per year and has shrunk about 3,100’/940m between the 1960s and 2001. 1

The glacier has thinned by 40-50’/12-15m over most of the length. Everest Base Camp is lower today due to the ice melting. In 1953 when Hillary and Tenzing summited, EBC was about 17,454’/5320m; today it is 17,322’/5280m. Between 1962 and 2002, the Icefall thinned by an average of 56’/17m, about a rate of 1.3’/39cm per year.

Long-time Everest guide Russell Brice commented told me in an interview in 2017 that this melting may result in safer Icefall for climbers. But he added the Western Cwm may one day become the major obstacle of the South Col route:

But on Everest looking at photos from above, it seems that the Icefall between BC and C1 is actually getting easier and arguably safer. It also seems that several of the hanging glaciers above the Icefall are now leaning back and seem to be less active than what we experienced in 2012, again this can be explained by the warm temperatures at this altitude.

However it seems to me that the crevasses between C1 and C2 are getting deeper and are now longer which results in climbers having to walk longer distances as they zig zag through these crevasses, and of course this has also resulted in some longer ladder crossings over very deep crevasses. I will not be surprised to see that we will need more ladders between C1 and C2 than before. Maybe even at the bottom of the Lhotse Face as well.

Judging by the reports from 2023, it appears the long-time Everest veteran who has now sold his company, Himex, was spot on. The route through the Icefall is faster and flatter, while the trek between C1 and C2 has to navigate massive crevasses.

The First Icefall Climbs

George Mallory, while seeking a route to climb to the summit of Everest, is said to have sighted the Icefall in the early 1920s and said it was “terribly steep and broken … all in all the approach to the mountain from Tibet is easier“5 thus shifted his efforts to Tibet.

It wasn’t until 1950, when Charlie Houston and Bill Tilman led a British reconnaissance team to scout a possible route from Nepal, that the Khumbu Icefall was considered feasible.

In 1951, another British team led by Eric Shipton climbed thru the Icefall but stopped just short of the top due to a wide crevasse. To cross the crevasses, the early expeditions used long tree trunks brought up from the treeline after they ran out of ladders.

A Swiss team in 1952 overcame that obstacle by climbing into the crevasse and crossing a dangerous snow bridge. They reached 8500 meters using today’s Southeast Ridge route but failed to summit. Of course, John Hunt’s 1953 British expedition made the first summit using that same route.

The Hazards

There are multiple hazards within the Icefall that have taken lives. I used the Himalayan Database to analyze the non-illness deaths between 17,500’/5400m and 19,500’/5940m, and that was in the Icefall proper. There were 45 total deaths in the Icefall or 23% of the 194 total deaths on the Nepal side from 1953 to 2019.

The 45 deaths broke down as follows:

- Avalanche onto the Icefall: 22 deaths or 49%

- Section of Icefall collapsed: 15 deaths or 33%

- Falling into a crevasse: 6 deaths or 13%

- Fall: 1

- AMS: 1

While I cite specific deaths to help others, I extend my condolences to all family, friends, and teammates of these tragic events.

Crevasse: 6 or 13%

Falling into a crevasse is quite common in mountains from Mont Blanc to Rainer to Everest. I fell in one above Camp 1 in 2002! On Everest, the standard protocol is to be clipped into the fixed rope at all times while moving up or down the Icefall so that if you step on a soft snow bridge and fall into a crevasse or slip off a ladder, the rope will catch you. Sadly, many falls into crevasses were the result of not being clipped in.

In 2005, a Westerner fell into a crevasse while crossing a soft snow bridge. Adventure Consultant team members who witnessed the fall all agreed: “It was clear that this climber was not clipped into the fixed ropes at the time of his fall; thus, a slip which should have been quickly arrested resulted in a fatal fall over a 10m drop.” 3

In 2012, a Sherpa fell from a ladder while not clipped into the fixed ropes and fell 150’/46m into a crevasse. 4

Icefall Collapse: 15 or 33%

The next hazard is being hit by an ice structure collapsing within the Icefall itself. There are many towering seracs (ice towers) that can fall over as the Icefall shifts or an entire section can simply collapse under a climber – remember, it can move a meter each day and can shift suddenly with no warning. Amazingly, this event is not very common but can easily be the cause of death.

A tragic example is from 1972 when an Australian climber supporting Chris Bonnington’s British Everest SW Face Expedition was ferrying loads. He entered the Icefall but was not seen again. A search team found a big area of the Icefall that had collapsed and assumed he was in that area when it happened. In 2008, his body was found at the foot of the Icefall. 2

Avalanche: 22 or 49%

Ice falling off the West Shoulder of Everest has resulted in massive casualties and is widely considered the most pressing danger in modern times. This is the serac Russell Brice mentioned earlier, and perhpas one that fell today.

There have two major events. In 1970, six Sherpas were killed while supporting a Japanese expedition. In 2014, one of the worse days in Everest history, 16 Sherpas died on 18 April when a hanging serac released as the Sherpas were waiting for a ladder to be replaced over a crevasse as they were ferrying loads to the higher camps.

In the Autumn of 2019, a house-size piece of ice was barely hanging on about 3,000 feet above the Icefall. All of the teams attempting Everest that season ended their efforts, fearing the serac would release just as they passed underneath, similar to 2014. It’s eventually released, leaving a debris field across the Icefall.

Who Does the Work?

The route thru the Icefall to Camp 2 is put in and maintained by a small team of Sherpas aptly called the Icefall Doctors.

On the south side, the Icefall Doctors, a team of eight dedicated Sherpas, install, aka “fix” the route from Everest Base Camp to Camp 2 in the Western Cwm each year. They first scout the route for the safest and most direct path, and then they carry on their backs hundreds of pounds of rope, ladders, ice screws, and pickets into the Icefall and the Western Cwm to create the route.

The ropes must be reset each season because the ultraviolet rays from the sun will rot the ropes causing them to fail under the weight of a climber’s fall. In addition, the route must be maintained daily through the season, given the Icefall is a moving glacier and can move up to three feet a day. This movement will cause ladders to drop into crevasses, bend them, or move them into a dangerous area. The Doctors inspect the route at least once a day throughout the season to keep it open and safe.

From Camp 2 to the summit on the south side, the Expedition Operators Association (a group of guide company owners) awards the contract to set the line from C2 to the summit. In 2023 it was awarded to Imagine Nepal.

Sherpas carry ropes and anchors on their backs and work together to fix the “fixed rope,” aka safety lines to the mountainside. In 2017, a major change occurred when the Nepal government allowed the ropes and anchors to be helicoptered to Camp 2, thus saving an estimated 78 Sherpa loads thru the Icefall. This was a pure safety decision. The labor and material are funded thru climbing permits or collections from the teams.

It’s a difficult and dangerous job. In 2013, Mingmar Sherpa, one of the Icefall Doctors, died after falling into a crevasse between Camps 1 and 2 in the Western Cwm.

The Route

In the past decade, it had shifted more towards the West Shoulder because it was faster for the Icefall Doctors to create the route. But the danger was obvious with the serac looming overhead. Looking at old maps and pictures, long-time veterans Pete Athens and David Breashears suggested the route should return towards Nuptse as it was in the 1950s.

Starting in 2015, the Doctors did just that making it shorter and safer. The route was not fully tested as the earthquake ended that season early, but in 2016 and 2017, they used the same path with good results, albeit with some sections being steep and difficult. Similarly good results in 2018 and 2019.

Safety in the Icefall

With all of this history, how do you protect yourself while climbing in the Khumbu Icefall?

For foreigners, it may take over 6 hours to climb to Camp 1 on the first rotation. Once they are acclimatized, that time can be cut in half, but most people still take four to five hours. This means leaving base camp no later than 6:00 am. However, most teams are on the ice by 4:00 am.

Sherpas will leave as early as 1:00 or 2:00 because they make a round trip. Impressively, they take the same time for a round trip as a foreigner does one way!

Skills Review

Most teams will take a few days to review basic skills before entering the Icefall. Sherpas will set up a short course with a couple of ladders and a fixed line running over a large block of ice. While it may seem odd to others for anyone already at Everest Base Camp to practice clipping on and off a fixed rope, use a jumar, or front point on steep ice with crampons, this review sharpens everyone’s skills and is a good use of time.

Safety Habits

These are the most common precautions climbers use to protect themselves:

- Never be in the Icefall when the sun is touching the ice, thus heating it up and causing movement

- Always be clipped into the fixed rope, including on ladders

- Never stop for more than a few minutes at any location in the Icefall

- Move as fast as you can safely

- Let faster climbers go by

But even these steps will not prevent something unexpected from occurring. The 2014 serac realize occurred well before the sun hit the Icefall. It was around 6:45 am, and the sun usually touches the ice around 10:00 am. Also, ice screws that attach the fixed ropes to the ice will melt out, removing the safety net provided by the ropes. So the best strategy is to move fast, be confident, and have extensive experience climbing in crampons on steep snow and ice – the more experience, the safer you will be.

Alan crossing a ladder from my 2008 climb:

And a video I took in 2014 after the earthquake flying over the Khumbu Icefall:

references

- https://glacierchange.wordpress.com/2009/12/09/khumbu-glacier-decay/

- http://www.frof.ch/absent-friends/tony-tighe/

- http://www.mounteverest.net/story/EverestshowsitsdarkestfaceTwodeathsinthreedaysMay32005.shtml

- http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/everest/blog/2012-04-21/tragedy-on-the-mountain?source=news_sherpa_fall

- https://books.google.com/books?id=Td0rVmVnkR8C&pg=PT49&lpg=PT49&dq=terribly+steep+and+broken+george+mallory&source=bl&ots=SYBw3DVWEU&sig=tGcuWRnMqpxDyxCAGom55ntaKJk&hl=en&sa=X&ei=aCrkVLvfOonXggSG1ICYAQ&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=terribly%20steep%20and%20broken%20george%20mallory&f=false

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything!

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can hear #everest2022 podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

Summit Coach

If you dream of climbing mountains but are not sure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers throughout the world achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 25 years of high-altitude mountain experience, including summits of Everest, K2, and Manaslu, and 30 years as a business executive.

4 thoughts on “Everest 2023: First Deaths of Season”

Hi Alan, as always, thank you for your excellent coverage of Everest.

There is a small error on your website. One of the headers says 2013 instead of 2023.

Thanks

„Deaths from avalanches and melting ice have increased in recent years. This week, near Chamonix, France, four skiers were killed in an avalanche from the Armancette

-Death on avalanches have increased… well Not in France .. See article below and analysis from Anena

– avalanche of Armancette Glacier has nothing to do with melting ice … please read the articles about this … also Not 4 but 6 deaths… this Kind avalanche is absolute a rare Event !

https://www.montagnes-magazine.com/actus-avalanches-bilan-saison-2020-2021

Malgré tout, sur les dix dernières années, la tendance reste à la baisse, avec environ 27 décès par an sur la dernière décennie contre 32 en moyenne sur la décennie précédente, et ce sans tenir compte de l’explosion (non quantifiée) de la fréquentation en montagne.

That report was from 2021. You are correct, Kerstin, it was not “melting ice” but as I mentioned, from an avalanche. The mayor of the town of Contamines-Montjoie, Francois Barbier, told Agence France-Presse it was “the most deadly avalanche this season.” I’m glad avalanches are rare in France.

Comments are closed.