Over 9, 000 people died in April 2015 from a 7.8 magnitude earthquake near Kathmandu. And no one summited Everest – from either side, from any camp. Summits don’t matter.

Over 9, 000 people died in April 2015 from a 7.8 magnitude earthquake near Kathmandu. And no one summited Everest – from either side, from any camp. Summits don’t matter.

As has been my custom since 2002, I will summarize the season but this time from my first hand experience as I was climbing Lhotse which shares 80% of the route with Everest. I was between Camps 1 and 2 when the 7.8 magnitude earthquake reached the Western Cwm.

This summary, while about the Everest season, is also about a human tragedy where thousands lost their lives, multiples of that are now homeless and many no longer have a way to make a living. Earthquakes are mean beasts, natural disasters, that strike with no warning, destroy at random.

I spent one evening this week speaking with helicopter pilots and people who have just returned from the earthquake epicenter regions. They say there are villages flattened, with landslides and down trees seemingly erasing entire villages off the trail systems – these are areas trekkers seldom touch, nor apparently relief agencies at the moment.

There are many, many small, individual efforts to reach these villages in addition to the large scale multi national efforts – the progress is not for lack of trying but it all seems to be moving too slowly. The largest organizations with resources to hire helicopters, deliver food and medicine are making a real difference.

If you want to make a donation where your money makes an immediate difference in Nepal, these are a few suggestions

- International Medical Corps

- Juniper Fund

- Himalayan Stove Project

Cholera is a growing concern with dead animals, and humans not being cremated or buried. Once this takes hold, the fear is the death toll will sky rocket. For an excellent overview of impact on Nepal as of 3 May 2015, please see this article on the Economist.

High/Low Expectations

The Everest 2015 season began with much trepidation, and attention. The number of permits issued surprised even the most jaded Everest observer: 358 individuals for Everest 114 for Lhotse and 56 for Nuptse – these were record numbers.

The Everest 2015 season began with much trepidation, and attention. The number of permits issued surprised even the most jaded Everest observer: 358 individuals for Everest 114 for Lhotse and 56 for Nuptse – these were record numbers.

With 16 mountain workers killed after an ice serac fell onto the Khumbu Icefall and over 40 trekkers killed in a snowstorm in the Annapurna region last autumn, many in Nepal feared the industry would take a hit with lower numbers. Some thought Everest climbers would prefer to climb from Tibet or trek in Bhutan.

However, history shows us once again that it is a fine predictor of the future. After record deaths in 1996, 2006 and 2012, the following year delivered record climbers on Everest; 2015 was no different. Even on Everest from Tibet for 2015, records permits were issued, over 200 foreigners .

The Everest Machine continued to be strong. Including the foreign permits, local Sherpa, Tibetans, cooks, cook boys, porters, over 1200 people were gathered on both sides of the world’s tallest peak, awaiting their turn for the summit. The human psyche is an interesting phenomenon.

Migrating towards EBC

Thus in early April people streamed into Kathmandu, flying to Lukla or driving to Chinese Base Camp on the north. The weather was, interesting. A few weeks earlier, Sherpas from the largest teams had already visited Everest Base Camp (EBC) at the foot of the Khumbu Icefall to mark spots for their teams and reported deep, wet snow everywhere – 3 feet of the white stuff.

Thus in early April people streamed into Kathmandu, flying to Lukla or driving to Chinese Base Camp on the north. The weather was, interesting. A few weeks earlier, Sherpas from the largest teams had already visited Everest Base Camp (EBC) at the foot of the Khumbu Icefall to mark spots for their teams and reported deep, wet snow everywhere – 3 feet of the white stuff.

The trails were filled, as were the teahouses; trekkers and climbers alike jammed into the stone and wooden structures, staff short tempered trying to meet the need. The promise of Wifi, fell short with schemes and technical problems thwarting the promise of Facebook selfies or emails back home. Yes, a first world problem in a third world country.

Capturing the Moment

Video cameras were as common as Dzos and yaks. It was reported that eight major film crews were on the south side this year, all waiting for some kind of Everest disaster so they could capture the human drama, package for television and make a name for themselves, until the next reality show. The only question was, if they could be at the right place at the right time.

Writers and reporters from newspapers to magazines to websites, called contacts to get their background stories pre-written as early as February. Many published a soon to be annual article on April 18, the anniversary of the Sherpa deaths in the Icefall. A week later it would be worse.

Arriving at EBC, it was stark, rolling glacial hills covered in white powder, and it was cold, extremely cold. Mid April is supposed to be somewhat warm. The traditional weather patterns for the past decade: clear, cool mornings changing to afternoon light snow showers changing to crisp clear nights – 2015 was full of harsh cold and heavy snow.

The “New” Everest Route

The team of specialized Sherpas, aka the Icefall Doctors, had arrived in mid March, aerial photographs in hand with expert consulting from some of the Everest climbers around, their remit was to find a “new, safe route” through the Khumbu Icefall.

The team of specialized Sherpas, aka the Icefall Doctors, had arrived in mid March, aerial photographs in hand with expert consulting from some of the Everest climbers around, their remit was to find a “new, safe route” through the Khumbu Icefall.

Last year’s route hugged the West Shoulder of Everest, putting each person in the direct fall line of the hanging serac. The consequences were deadly when it released. For 2015, they wanted to return it more towards the center, or near Nuptse, climber’s right, to reduce this exposure.

As teams got settled at EBC, everyone wanted to know about the route. Where was it, was it safer, how many ladders? The early reports said shorter and safer. But when the first westerners entered the Icefall, there was a huge surprise.

The lower section was in fact almost direct, no ladders until half way, or higher; it was fast. But the top section had an obstacle, some call it an aid, that would stop both foreigners and Sherpas alike: two vertical snow walls near the top had ladders, six to be exact, lashed together with nylon ropes, that would provide access to the Western Cwm.

The Docs had put one ladder on each of these sections but it was taking the world’s Sherpas five to ten minutes to overcome each. With hundreds of individuals each day, this was a bottleneck waiting to happen. More to the point this section would prove pivotal two weeks later in the 2015 Everest story.

With the feedback, the Docs promised to add more ladders plus a rope to used to rappel or abseil, down. This should reduce the congestion. However, the weather hit again, hard. A week of cold and snow stopped all activity. Everest 2015 was falling behind schedule.

Since 2005, the route to the summit from the Southeast Ridge was either finished or had all the needed ropes and anchors positioned at the South Col by May 1. It was now April 25 and the thin nylon safety line was only set to Camp 1 at the base of the Lhotse Face, over 7,000 feet short. All the needed rope and anchors were still at EBC. It would take 80 Sherpas loads just to move this mass of gear to Camp 2, much less get the line set to the summit.

The Expedition Operators Association had implored the Nepal Ministry of Tourism to let them use helicopters to move this safety equipment higher thus keeping the Sherpas safe from what was viewed as unnecessary work. But their request had been denied. This was not new, the same ask and deny cycle had been going on for many years, led by Russell Brice and Guy Cotter. But after the deaths in 2014, they thought they had a good case – it appeared not to be true.

On April 19, the weather took a turn – for the better, it was like mid April should be. Teams took advantage of this break to make their first climbs into the Icefall, hone skills near base camp or just pack and repack for their first acclimatization rotations to the Cwm. It finally felt like the Everest climbing season had started on the south side.

Our team left at 2:00AM on April 23 – presumably to get ahead of the rumored crowds heading up that same day. While additional ladders had been installed by the Docs, the chance of waiting was too high not to loose a few hours of sleep in order to miss it. We started higher by headlamp, a clear sky overhead, Sherpa trains going up and down. It felt good

Kami and I reached the upper ladders just after sunrise. I looked around to take it all in. I saw the horseshoe ice serac hanging from Everest’s West Shoulder, similar ice cliffs off Nuptse and Pumori, the 21,000 foot snow cone, was just behind base camp. This was part of why I climb, the feeling of freedom, rarefied air, teammates along with a shared purpose. Yes, this was it.

Satisfaction at Camp 1

We reached Camp 1 where we would spend two nights. It was business as usual as the site situated at the top of the Khumbu Icefall filled up with expedition tents. The quiet was replaced by hissing stoves, chatter and the occasional small avalanche that always welcomed humans to this place.

On Saturday, April 25, we left for Camp 2. The prior day we had taken an hour walk up the Cwm to further our acclimatization as we knew the route. As we walked this day, the clouds moved in and it was lightly snowing – no worry as it should only take a few hours to make the traverse. Our teams began to spread out like normal. Then it happened.

Avalanche!

Near the front, I stopped in my tracks as a huge avalanche announced it’s arrival to my right, off Nuptse. It was a crushing sound. I looked right. A few seconds later, an equally loud rush of snow, ice and air was delivered off the West Ridge of Everest. It was almost impossible to see what was unfolding as the low clouds and snowfall obscured any clear view – but we knew they were avalanches, and they were close.

Garrett screamed out “pull up your buffs!” This was to keep the snow out of our mouths, in other words to keep us breathing and alive. We stood helpless in the Valley of Silence as the Western Cwm is oft called but it was nothing but silent this Saturday, 4 minutes before noon.

I caught a glimpse of avalanching snow and pointed it out just as I heard over our radios, “Earthquake.” It was Billie, few hundred yards behind us, moving alone in the middle of the pack. Just then, my world dropped out from underneath my feet, and simultaneously throughout this part of Nepal.

Earthquake!

Everyone has a slightly direct recall of that moment, but I felt the snow floor drop two inches underneath my feet. I stumbled to maintain my balance, then it happened again. That was the moment I knew I was in a huge earthquake while in the Western Cwm staring at Lhotse ahead and Everest to my left. I felt helpless, totally vulnerable; at the full mercy of planet earth, with no options.

As my head cleared, a new thought entered: what of the fragile Khumbu Icefall, base camp, how far did this earthquake reach – the north side, Kathmandu? I had questions and no answers. Soon the reality set in, delivered in short sound bites over what radio transmitters still worked, the news was devastating.

We moved faster towards Camp 2 where part of our Sherpa team was waiting. Faces were bleak, no smiles, little emotion. The news was dire – first reports said Everest Base Camp was decimated – moved west by hundreds of meters on liquefied snow and ice – everything was gone – there were casualties. We sat quietly as the news sank in. We had no way of vetting the stories and no reason to doubt them.

Then, the crushing blow, our base camp doctor, Eve, was in critical condition from a head injury. We sat quietly, heads lowered, staring at our 8000 meter boots.

Two hours later, around 3:00pm, the earth moved again. A day later, a second earthquake delivered another blow. We knew the icefall was ruined, how could it not be? The ladders across the crevasses were tenuous at , the vertical ladders attached to snow with screws and aluminum pickets – they were never constructed to handle a major earthquake.

The crevasses has become spokes on a huge gear, spinning slowly, without concern for what was in its teeth, crushing anyone or anything that dared to test its strength.

Reality

I never considered taking a helicopter back to EBC, not once, but soon the harsh reality set in – the Khumbu Icefall is a fragile set of house sized ice blocks leaning against one another – all moving in slow motion but moving nonetheless. If one moves, something else has to move – it was real life dominoes. They had moved, everything had moved. To enter it now would be risky, fool hardy, even suicidal – more than the normal risk everyone accepted when climbing it.

We were safe at Camp 2, food, and fuel to survive many days – but not forever. The route from Camp 1 to Camp 2 had changed, crevasses had closed, new ones had opened; the ladders we had used were swallowed up, disappeared – perhaps one day to be spit back up 2,500 feet lower at base camp. The power of the glacier, the earth was on full display. I had felt tiny on the summit of Everest in 2011 but now felt minute, insignificant – in the wrong place.

The radios chattered. Guides from several commercial teams were making their effort to fix the route – a few from base camp and a few from camp 1 – the hopes of 170 people now in the Western Cwm lay on their shoulders to repair the ladders, find a new route or pull a rabbit out of the glacier hat that would allow us to down climb to base camp.

The crevasses were large this year near the top of the Icefall. Perhaps as a result of the new route of just a function of 2015 – but they were too wide to cross without aid, too deep to climb out of without unique skills, ice axes, ropes and specialized gear – the Khumbu Icefall had been transformed into a series of death traps that few expert climbers would enter, much less the 170 people in the Western Cwm.

“We are coming back – too warm, no route.” Was all that was said on the radio from the expert climbing guides. And with that we knew the remaining option was to consider the helicopters. They had tried their to no avail, the warming temperatures of mid day plus another aftershock had taken them as far as anyone would expect, and more. Now re was the better part of valor. This was not time for ego, pride or vanity – this was serious.

Down climbing was not an option – for anyone -guides, foreigners, Sherpa or Nepali cook boys.

No one would reenter the Khumbu Icefall in 2015, even the vaunted Icefall Doctors.

Helicopters

The helicopter business had been good this spring. Flight sight seeing was in full motion, teams flying gear in and out of base camp, some of those who did the technique of acclimatizing at home in altitude tents, took the chopper almost to base camp to save time. At times I felt like I was camping at an airport and the flights began promptly at 7:00am and stopped only when the clouds moved in late afternoon. I cussed them but now knew that were our path back to base camp – or what was left of it.

On Monday, April 27 we left Camp 2 for Camp 1 and the makeshift helicopter pad. The Western Cwm route we had ascended was unrecognizable. It was a new terrain. I kept looking up at the steep walls surrounding the Valley of Silence. Camp 1 was in a more precarious location that Camp 2, closer to the walls, exposed to direct hits from avalanches. Some people had their brush with them a few days earlier, others had died from them a few years earlier. With the instability, this was not a place to linger, everyone waiting anxiously for the “womph, woomph, woomph” of helicopter rotors beating against the thin air.

There were two makeshift landing pads scooped out of the snow. 50 people stood at one, about 25 at the other – more were to come. There was order to the chaos. Again, commercial guides did traffic control, most everyone followed their instructions. Some teams choose to skip the first wave of flights, wanting to see if the route could be repaired, they surrendered to the inevitable the next day.

The pilots showed their skills as they approached the pad, hovered momentarily as the passengers positioned to jump on board as soon as the skids touched down – it was a high altitude ballet that was unthinkable a few years earlier. In a few hours, 150 people were moved freeing up the choppers to help others in need. Two by two, foreigners, Sherpas, Nepalis were saved that day.

Base Camp Horrors

I stepped off the helicopter to familiar faces from other climbs, they shook my hand, suggested I get something to eat and drink before heading higher to my base camp. Expectations had already been set – there was nothing left and Eve had died. I went in search of my Colorado climbing mate, Jim but failed to find him. I knew he had taken a previous flight down from Camp 1 so I knew he was safe, but I wanted to see him.

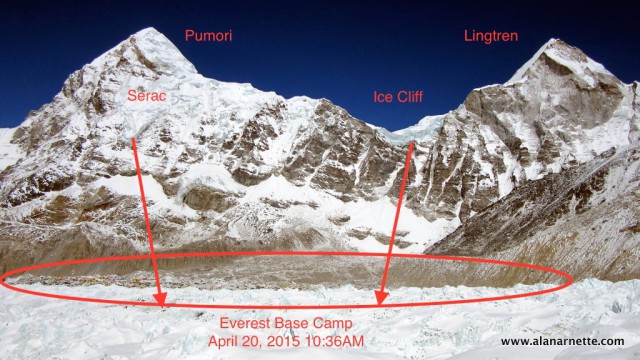

I slowly walked from the lower end of EBC towards the center, ground zero if you will. The earthquake had shook loose decades, perhaps centuries old ice cliffs off Pumori and the steep ridge that led to Lintgren. These cliffs had released before but only gently sprayed base camp with a soft puff of cold snow – there was nothing gentle or soft about what had just happened.

As the mountains moved, and in fact the ground near the epicenter rose by three feet, the cliffs were pulled down by a deadly combination of gravity and plate tectonics. It sped down, gaining terminal velocity until it hit a small dip in the landscape that usually protected base camp from such release. But the volume was too great, it gained speed when compressed in the dip, picking up speed it also picked up loose rocks, boulders – they became projectiles hitting anything, and anyone in their way.

It was a F5 tornado combined with IEDs all in an environment of nylon tents. The only place to hide was behind a larger rock, even then there was no certainty.

The carnage was large, measurable and deadly. Doctors from expeditions and the medical volunteers at EverestER created a MASH unit at one untouched camp. Soon, the injured were carried on the shoulders of others across snow, ice and rock. Blood dripped from the plastic tarps, on the arms, and heads of the living.

For many of the doctors this was the second year in a row they served such duty, but this time instead of dealing with suffocation, they dealt with blunt force trauma. I’m not sure their training prepared them for such triage but they performed well, they were once again heroes in an unannounced war.

Home?

As the aftershocks relented, the hundreds at base camp began to breathe again. Thoughts drifted to home, loved ones. The Sherpas tired to call using the cell phone system ubiquitous throughout Nepal and the Khumbu, the connection didn’t go through. They used the satellite phones of expeditions and individuals with the same result. Some left for the walk back home, no one ever complained and sent them off with hugs. Most stayed to be with their charges, no questioned asked, the loyalty was extraordinary and unexpected given the circumstances – and appreciated.

I moved slowly towards our camp, expecting to find nothing – my tent platform scrapped out of the glacier a few weeks earlier. I spotted a huge rock builder, twice as tall as myself – I called it Cell Phone Rock as it was the only place near our camp I could get a signal. I climbed towards it.

Our puja alter was still standing – the 3 inch thick puja pole – a tree trunk really, was broken like a twig two feet above the top of the alter, the prayer flags that strung across our camp were gone. All the large tents we used for cooking, eating, communications, storage – tents that stood 10 feet high, 15 feet wide, 30 feet long were gone – no trace.

I walked in with a few of my teammates. I passed a shoe, a playing card – the two of hearts – a crushed laptop computer; a picture.

Extreme Loss

I saw my tent, slightly above our camp proper. A few weeks earlier, I commented to Kami that my tent, being next to the dining tent, was very noisy. He took it upon himself to move me to a quieter spot. By chance it was behind a 15 foot bump on the glacier – that proved to protect half my tent from the directly blow. I lost nothing, my computer nestled in my sleeping bag where I left it, my other gear wet but safe in duffel bags. Kami’s gear had the same good fortune as did most of our team. Sadly, there was looting just after the avalanche, many people found their climbing gear but not money, passports credit cards.

But we had lost a dear teammate, Marisa Eve Girawong. She brought smiles, compassion and skills to our camp as our doctor and base camp manager. It was her face I could only see as I sat crossed leg in my pile of “stuff” envisioning the moment she must have experienced; and that of 18 others that Saturday – and the tens of thousands through central Nepal – and the millions who are now homeless.

Yes, I was lucky, I know that. I am grateful.

We collected our gear and left for the closest village. I was determined not to leave a scrap behind. I picked up the odd piece of trash as I walked. The Indian Army was staying behind to help – they are an incredible asset to Nepal – a good friend.

I walked slowly to Gorak Shep, alone in deep thoughts.

The Housewives of the Khumbu

A few days later I approached Pangboche where Kami (Ang Chhiring Sherpa) lived with his wife. He invited me to visit his home – an honor. We had been through a lot together with summiting Everest in 2011 and K2 last summer, now this. I call him my guardian angel in the mountains. He calls me his father due to lack of hair and gray beard but I’m only eight years older than him!

Alone, the rest of the group had gone on to Dubuche for the night, I walked slowly as the sun set and the clouds moved in. How could this happen to such gentle people, such a poor country as measured in money, such a giving culture?

I knew where his home was, he had showed me after we had our blessing from Lama Geshi. I entered the trees that decorated his village – it was like moving into a different reality – a refreshing sense of life, peace and hope. A young girl passed me with a basket of potatoes on her back supported by a tumpline around her forehead. “Namaste” she said with a smile on her face. I smiled back, chocking back the emotion from this simple greeting.

“Alan”, by now I was familiar with this call as Kami often called to me on the big Hills when he thought I needed help – which was often. Once gain, without knowing it, he was watching out for me. He was standing outside his stone walled home, adorned with a green metal roof. I waved. He waved back. I climbed over a rock wall, designed to keep the pesky yaks out of the vegetable garden and walked the dirt path towards him.

We shook hands, then embraced. “Come in, come in.” He took my pack, ice axe still affixed. I walked into a very dark room, serving as the lower part of his home. A soft “Mooo” greeted me, a baby cow sat on fresh grass chewing her cud. The lower part of a Sherpa’s home is for the animals, the upper part of people – nothing goes to waste in the Khumbu.

I climbed the steep wooden stairs to the next level. His wife, Lhapka Dicki Sherpa met me. Her huge grin, her smile, her presence set me both at ease and filled me with joy. She hugged my stomach as her head reached my chest. “Lucky, lucky, lucky” she repeated in her Khumbu accent. She held on tight and she looked up at me. Kami stood by with an equally big grin.

I moved from the small room that served as a kitchen to the main room, perhaps 20 feet by 40 feet, that served as guest room, living room, bedroom and monastery. On the far wall, wooden bookcases with glass doors, held Tibetan prayer books. Once a year, Kami had a Lama come to his home and spend days praying and blessing his home and family. Before each expedition, he did the same. I was grateful.

Lhapka brought us black tea and chang – an obnoxious Khumbu moonshine. I sipped mine but she kept filling the mug to the rim. Kami just smiled.

Kami wanted me to meet his mother, she lived next door in a similar arrangement. Once again, I navigated the black space of the lower level only to find her along with Kami’s sister and two neighbors, chatting away in the “kitchen” sitting next to the fire. Their smiles were large, laughs relaxed as Kami introduced me. What they were saying will be a secret forever – I had no idea.

Each one hugged my belly as I held their hands tightly – they were tough, strong yet smooth after a life of hard work, love and prayer. The prayer beads, close to their sides, were well worn.

Kami’s mother began to talk. He told me (as translated by Kami) how happy she was when her sons were home, away from the mountains – you could see the worry in her eyes, and the joy at having Kami back home. Her friends smiled and nodded in agreement.

As I left, Kami talked to me about the next climb ….

Kathmandu

The flight from Lukla left as much on time as anything does in Nepal. I landed just as the sun was warming up the capital. It was quiet on this Saturday morning, a week after the quake. I noticed a few rock walls strewn across the streets but nothing like I expected, similar to the suggested damage in the Khumbu, but thankfully very different. To be sure there was damage throughout Nepal just not where I had been.

The airport was crowded – with rescue helicopters from India, UN planes, cargo full of food, tents, tarps — emergency supplies crying out to get delivered to the remote villages near the epicenter. But the bureaucracy of Nepal had everything at a life threatening halt. The demanded each time had to be inspected, they had waived taxes on the imports, but the logjam was costing lives every second.

I walked the streets as the city awoke. People milled about as heavy helicopters flew above. I hope their missions were successful.

Everest

Almost immediately after the earthquake, climbing teams made plans to return to Kathmandu, but a few individuals, no organized teams ever seriously considered attempting the summit, stayed on hoping the Icefall Doctors would return, they had some injured members but no deaths as had been widely reported.

On May 3, the Nepal Ministry of Tourism said “Everest is closed” (source) due to the Icefall being impassable, then on the following day (source) they said it was officially open and anyone with a permit may attempt the mountain. As of this writing no one remained at EBC with the intention to climb. For the first time since 1974, Everest would have no summits by any route, from any camp, by any means.

The China Tibet Mountaineering Association (CTMA) had already declared climbing closed from Tibet and all permits would be honored for three additional years. Nepal took 364 days to confirm the 2014 permits would be honored through 2019 in a stunning display of indecision. There are requests for Nepal to honor this years permits, thus the waiting games begins anew.

Sadly, the government seems to be incapable of having a clear vision of how to manage their mountains, leaving climbers and trekkers continuously questioning policies. All their promises of improvements from weather forecasts, GPS systems, rescue teams, actual liaison officers – none materialized.

With the earthquake, the situation will only get worse as the government struggles with the larger national issues. Perhaps it is time for the world’s climbers to focus on other countries.

Aftermath

It will take years for Nepal to recover, just like Haiti or another third world country. Money will flow in from well meaning people, some of it will reach those in need. NGOs will do their as will the UN and other global agencies charged with helping countries when a natural disaster overwhelms them.

As for climbing, well frankly who cares?

Climbing really only matters to those who make a living from it, guides, Sherpas, porters, teahouse house owners – governments. For the rest of us, it is a sport, sometimes a deadly one. If no one ever summited Everest again, it would certainly destroy a lot of dreams but more importantly, would impact the livelihood of many; that said, summits don’t matter.

My passion is climbing mountains, it keeps me alive and feeds my soul, but it is not worth lives. The deaths at base camp were part of a larger disaster, actual a tiny part in the overall tragedy; but the loss was real, shattering families. I know death happens daily around the globe in uncountable ways; these deaths were close to home, close to me and many who will never forget the experience.

Yes hundreds will probably return next spring to attempt Everest. Some operators will shift to the north, quietly, or in some case loudly, saying it is safer. People with nothing more than a Kilimanjaro summit will claim to have the proper experience – until something goes wrong. Guides will continue to save lives, doing what they do; and the Everest machine will continue even though it is clear it is time to let Nepal recover.

I don’t know when Kami will climb Everest again, his mother hopes never, I kind of agree.

Memories are Everything

Alan

4 thoughts on “Everest 2015: Season Summary – Summits Don’t Matter”

Always appreciate your reports about your experiences. Unless I missed it, you never quite say *you’re* not going back to Everest. Will you try to summit again later, perhaps once Nepal has had time to heal?

Hi Kelly, I summited Everest in 2011 so no need to return the south side for me. I was there this year attempting Lhotse, next to Everest.

Great post… sums up the emotions of everybody.

A moving post Alan – very well said

Comments are closed.