April 25 is always a difficult day in Nepal. This year, 2019, marks the fourth anniversary of the deadly 7.8 magnitude earthquake that occurred in Nepal taking 9,000 lives, including 19 at Everest Base Camp. I’m sure there will be many services, memorials and simple quiet moments to honor those who died, and keep their memories alive.

I wrote this narrative a few years ago about my own experience that day. I was going between Camp 1 and Camp 2 when the quake hit. It’s a moment in my life, I will never forget. So no big update today on what’s happening on Everest other than everything seems to be progressing according to traditional schedule with teams on both sides on their acclimatization rotations. I’ll get back to the regular updates tomorrow.

Now for this memory:

Some memories are so etched into your essence, that they will never go away and they will always be clear. The day my mom asked me “Now, who are you again?” The day I met Di and publicly committed to her in our backyard three years later. The day the Khumbu Glacier dropped by inches under my feet while hearing the roar of avalanches all around me. Yes, Memories are Everything.

Three years ago today, at 11:56 am April 25th, 2015, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake hit in Nepal taking 9,000 lives, including 19 at Everest Base Camp.

A Short Walk

I awoke on May 25, 2015 at Camp 1 with the rest of the Maddison Mountaineering Everest/Lhotse team. As usual for the first trip through the Icefall, we were all adjusting to the high altitude and a tough night at 19,500 feet. Louie, my fellow Lhotse climber and tent-mate, said “Glad we are only going to Camp 2 today, it’ll be a short walk.” His South African accent coming through strongly. Louie and I had summited Manaslu together in 2013 and had become good friends even though we were separated by half a planet. We packed our -20 degree down sleeping bags along with the rest of our gear into our packs, wiggled into our climbing harnesses, tighten the chinstrap on our helmets and started walking towards Lhotse. The clouds and fog soon covered up what is an amazing view of Everest, Lhotse and Nuptse defining the Western Cwm. But I had been there so many times that I felt like every detail was in my body and went on enjoying a light breeze and the occasional flake of snow on my face.

Progress is always a bit slow in the lower sections of the Western Cwm as you crawl in and climb out of several shallow crevasses. But even this small amount of work takes its toll at these altitudes. The team bunched up, all clipped into the fixed rope. Kami was in the lead with me following closely behind, as always, when I heard a loud pop and crash to my left. I looked towards Everest’s West Shoulder but only saw the flat white light of a dense fog. A breath later, another loud crash, this time to my right off Nuptse. “Avalanches?” I told myself, but two, with one after the other and with such high energy? Then I felt it. The snow and ice covered ground of the Khumbu Glacier dropped by two inches. “Whoa.” I said out loud to no-one. About that time, my mind was running fast, processing all the incoming signals, trying to make sense of a scary and confusing environment. Then it happened again – the ground shook and dropped another inch. Then it all made sense “EARTHQUAKE!”

Garrett yelled out “Put your buff over your mouth and nose.” His years of mountain experience told him we needed to protect ourselves from the incoming avalanche blast that was a certainty from one of the two nearby avalanches, if not both. I adopted the stance to fight a fast approaching tiger, legs shoulder width apart, focusing on maintaining my balance and low center of gravity not sure what would happen next. But then as quickly as the cacophony of sounds, shakes and uncertainty came upon us, it went eerily silent. It was clear that I had no control over my present or my future. We regained our composure and picked up the pace to Camp 2 where we would have shelter and food. The Sherpas were already there having established the camp a few days ago. Garrett took off fast leaving the team in the hands of the assistant guides.

Base Camp has been Devastated

Sitting in the dining tent about an hour later, the radio was full of chatter. Most of it in Sherpa or Nepali, but one voice came through clearly, and in English “Base Camp has been devastated.” And with that, I knew this was not a small localized event but something much larger in scope. The Sherpas began talking amongst themselves. There had been a large earthquake near Kathmandu. Village after village was destroyed, including those in the Khumbu. The Sherpas desperately tried to use their phones to call home, but the entire cell network was down. I offered my satellite phone but those calls didn’t connect given the local NCELL network was down. We sat in the dining tent silent, listening to the radio for any clue. I heard chatter around some guides trying to climb through the Icefall. “Base, we just had another strong aftershock so we are getting out of here ASAP before something comes down us.” The word was the ladders had fallen into crevasses and the Icefall was now impassable. Sitting at 21,500 feet in the Western Cwm, we might as well have been on Mars.

As the situation set in, we discussed various options. Risk down-climbing through the Icefall not knowing if the deep crevasses could be crossed with ladders missing. Wait until the Icefall Doctors could repair the route but with such a strong earthquake, aftershocks were a certainty and they could be extremely violent and strong. The final option was to see if the helicopters that had been visiting base camp several times a day could somehow muster a rescue mission for the 150 climbers, most of which are Sherpas who desperately needed to get home to help their families. Garret was nowhere to be found so Assistant Guide Conan Bliss was handling communications and passing on critical information, soon we would understand why. As the afternoon of April 25, 2015 continued, one by one everyone gathered in the dining tent, mostly to support one another. It was at this point around 4 in the afternoon that Conan simply said; “Eve has been critically injured.” The tent went silent. Tears began to flow as we internalized that one of the most gentle persons I had ever met, Marisa Eve Girawong, had been hit in the head by a flying rock and most likely would not survive. Eve was our base camp manager and expedition doctor. She worked as an emergency room physician assistant saving others, now her life was in someone’s hands. She was 28 years-old.

I had slowly befriended Eve, enjoying her gentle and intelligent style with engaging conversations. While receiving our blessing a couple of weeks earlier at Lama Geshe’s home, she asked him to bless three sets of prayer beads, one for each parent and one for herself. She talked about how much this meant to her and how excited she was to give them to her parents. Later that evening we learned she had passed away along with at least 17 other people at Everest Base Camp, scores were injured. As the shock set in, word came over the radio of wide-scale damage throughout Nepal with entire villages now covered in tons of mud from landslides triggered by the earthquakes. Families disappeared in a flash. The aftershocks were strong and frequent. Talk was of thousands dead, and the toll was growing.

I’m OK

I called Diane. We were in the second year of our relationship but I knew she was special and this was serious. I always called her Di but when I woke her up at 3:00 am I said, “Diane, I’m OK. There has been an earthquake.” and with that, told her the story and that we were trapped at Camp 2, but don’t worry. It was probably that moment that she realized what it meant to date a climber. I wanted her to hear it from me and not the news that morning. As in all disasters of this scale, often the first news is incorrect.

I posted two audio dispatches using my satellite phone to provide my perspective on what had happened to my followers. The first one was garbled but you get a sense as I sent it a few hours after the first quake. The second came the next day and is clear.

Becomes clearer 13 seconds in

And the update the next day saying we can’t return using the Icefall

Over the next two days, the rescue plan came together involving a fleet of rescue helicopters. On Monday, April 27 we left Camp 2 for Camp 1 and the makeshift helicopter pad. The Western Cwm route we had ascended was unrecognizable. It was a new terrain. I kept looking up at the steep walls surrounding the Valley of Silence. Camp 1 was in a more precarious location that Camp 2, closer to the walls, exposed to direct hits from avalanches. My friend Jim Davidson was hit by the air blast as the avalanches peeled off the walls of Everest and Nuptse. He later told me that he thought that was it.

There were two landing pads marked with huge red circles made of juice in the snow to help the pilots land. 50 people stood at one, about 25 at the other. The crowds of stranded climbers increased as the day wore on. There was order to the chaos. I made small talk with Louie. We both were afraid of what we would see at base camp. Everyone waited anxiously for the “woomph, woomph, woomph” of helicopter rotors beating against the thin air. Suddenly, we were rewarded with the sight and sound of the helicopters. Two at once, in perfect coordination. Seeing the helicopters appear at the top of the Icefall was surreal, something out of the movie Everest with Capitan KC Madan fighting to keep the chopper in the air in order to rescue Beck Weathers and Makalu Gau. Now almost 20 years later, helicopters can fly higher but the risks are very real, especially to the pilots. Louie and I were told to take the first chopper. Holding our packs to our chest, we ran low to the ground as a helper opened the door. The rotors were at full thrust. The sound was deafening. Snow was blowing like a ground blizzard. As I approached the machine, I glanced at the pilot. He was looking straight ahead, hands on the controls. If he was nervous, his expression didn’t reveal it. He was strong, brave, professional and a hero. Everything had been taken out of the helicopter except for the pilot’s seat. It was striped down in order to carry two people at one time down the 2,000 feet to base camp … in the thin air. I sat on the floor next to my friend. We exchanged glances of fear and relief. I pointed my camera out the window:

Base Camp Horrors

“Base Camp has been devastated.” The words would not leave my mind. I stepped off the helicopter not knowing what to expect. Willie Bengas came rushing by. “We have more people trapped.” he called out wishing me well. As I walked away from the landing pad, Greg Vernovage, IMG’s leader, came up and shook my hand. “Welcome back Alan, your camp is gone so use ours as long as you need it.” And he rushed away. A triage tent had been set up and doctors from every expedition had worked hard to save lives. One physician, Ellen Gallant, would tell me years later that she fell asleep on the tent floor and woke smelling blood. When she opened her eyes, she saw blood running across the tent floor. Louie and I started a slow walk towards the Madison Mountaineering base camp. As I walked, my mind was struggling to understand what I was seeing. Tent fragments everywhere, yellow from sleeping, blue from cook and dining. A random shoe on the ground, a playing card. The tree trunks used as a Puja pole to hold the prayer flags were snapped in two like a match stick. The force of the avalanche had made any struggle impossible. The place I had come to love so much had now become a place of devastation and death.

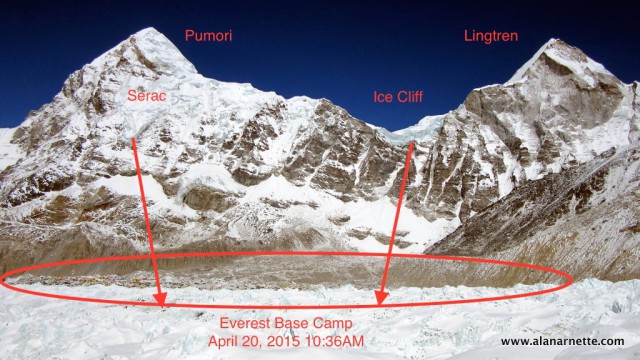

I looked up at Pumori, the source of the avalanche. The earthquake had shaken loose decades, perhaps centuries old ice cliffs off Pumori and the steep ridge that led to Lintgren. These cliffs had released before but only gently sprayed base camp with a soft puff of cold snow – there was nothing gentle or soft about what had just happened. As the mountains moved, the ground near the epicenter rose by three feet and the snow cliffs were pulled down by a deadly combination of gravity and plate tectonics. The snow and pressure sped downhill, gaining terminal velocity until it hit a small dip in the landscape that usually protected base camp from such release. But the volume was too great, it gained speed when compressed in the dip, picking up speed it also picked up loose rocks, boulders – they became projectiles hitting anything, and anyone in their way.

Louie and I continued our search for our camp. We thought we knew base camp but it had all changed and nothing was recognizable. Searching, we finally found the remains of our camp. It was mostly gone. The huge tents we ate in, the Sherpas cooked in, the storage tent, the communications tent – gone, simply gone. A few of the sleeping tents were still there. Amazingly, I found mine, it was shielded by a small hill from the brutal air blast. It had collapsed when the poles snapped. All of my gear was inside, including the prayer beads that I had asked Lama Geshe to bless as a gift for Diane. I thought of Eve. Two other teammates had stayed at base camp and survived. I asked David to describe what he saw:

Everest Closed

We left base camp for Gorak Shep later that day. The Nepal Government announced that Everest was closed and for everyone to return home as soon as possible. A day later they said it was “open” and the Icefall Doctors would return to support the climbers – neither was true but once again they were focused on positive press and not acknowledging the reality at over 9,000 Nepalis had just been killed. For us, climbing was the last thing on our mind.

We started the four day trek back to Luka. As we passed village after village, the rock walls that kept yaks away from potato fields had fallen over. The walls for homes, teahouses and monasteries had cracks or worse, some were totally collapsed, fallen into a rumble of rocks that looks like where they were found in the first place to build a home. Livestock was killed, hurting a crucial segment of the food chain. Cows were used for milk, to plow fields, to bare calves and for meat. To lose a cow was devastating. As we stayed in teahouses, the staff was smiling, friendly and as helpful as ever. Even in misery, they showed the spirit that caused me to fall in love with Nepal in 1997. Back in Kathmandu, the city looked almost normal until you walked the streets. Again, the poor building practice had enabled massive destruction.

A Strong People

I think about those days a lot each April 25, and in between. I am grateful for my own life and to those who helped so many. In the end 19 people died at Everest Base Camp, none on the Tibet side from the earthquake. While Everest made the headlines, it was the small villages here and there that paid the price. Landslides, rockfall, mud slides. Water holes dried up. People died under collapsed walls.The government was slow to help. International aid was held hostage by a broken and corrupt system. Even today, the third anniversary, many villages have not received the help they were promised. The saying was to “build again better” and to use easy and inexpensive structural techniques to help homes withstand another large quake. But in the hurry to prove to the world that Nepal was open to tourism, more shortcuts were taken. Sadly, we can expect similar carnage for the next 7+ earthquake.

Yet with all this, the spirit is alive. I visited Kami Sherpa as I trekked out. I drank milk tea with he and Lhapka Ditti, his wife. I held hands with his elderly mother and younger sister. They smiled even though their cow had been killed and the walls of their home were leaning. Nepal is resilient. The Sherpa character is strong, proud and in-tact. Today, is a day of mourning but also one of celebration for his special country and it’s special people.

Climb On!

Memories are Everything

Alan

If you would like to help the people of Nepal, my suggestion is to donate to the Himalayan Stove Project where I’m a board member. They donate clean cook stoves to families in Nepal. Anyone who has ever stayed in an older teahouse, or spent time in a Sherpa’s home anywhere in rural Nepal understands how their cooking with yak dung, or wood inside create a toxic smoky environment. The HSP solves this problem

5 thoughts on “Everest 2019:Remembering The Day Nepal Shook”

Thank you for sharing your memories. I’m sure reliving those horrible days are not easy. I also want to ty for making me aware of the Stove Project. Without this blog I would never have known. It made my heart happy to donate. I pray for those brave souls delivering the stoves to remote areas. Good job Allen!

I’ll never forget the noise of the helicopters flying up and down the valley, even when the clouds set in, I’d never seen a Sherpa panic until that day,

Memories are strong.

-Vic

I believe you mean April 25 in your opening sentence, I realized when I was trying to make sense of it.

Will be praying for all those who lost their lives on that tragic day. Thanks Alan, for sharing and caring. Glad you and Jim made a safe return.

Comments are closed.