Satire sprinkled with a few annoying facts.

As I sat down to write a recap of the 2021 spring season on Everest, these words came to mind: COVID, coverup, lies, misdirection, personal attacks, denials. Oh, and cyclones, wind, waiting, risk, and yes, summits. But, oh my, at what a cost? If 2019 was the year Everest broke, 2021 was the year Nepal broke Everest.

With 2020 lost to the global pandemic, Nepal was desperate to rebuild its tourism industry. Last autumn, a few teams returned, but spring was the key. Everest served as a light to a swarm of eager climbers. The Ministry of Tourism, MoT, knew this and successfully lobbied; well, it’s unclear who they lobbied, but they removed any barriers that would discourage visitors.

Empty Promises of Safety

Early in 2021, the MoT spoke of quarantines, that vaccines would be required, and visitors would undergo extensive testing upon arrival before traveling to their mountain destination. However, with a low flow of permit applications into their department, all it took was a note to a friendly reporter and an article in the newspaper to erase the rules and wash the walls away. Permits skyrocketed, and guests began to arrive. So many for Everest that they issued a record 408 climbing permits to foreigners and another 334 for other Nepali peaks. The total income from these climbing permits broke $4.6 million, with Everest accounting for $4.2 million, a massive amount of money for this impoverished country. The champagne flowed at the MoT, but they knew the system was broken and plotted a strategy to hide the problems.

Threats and Censorship

In 2019, a viral photo of scores of climbers stuck between the South Summit and Summit made world headlines that Nepal was mismanaging its cash cow. Calls came for quotas, and limits like the Chinese had already implemented. The MoT floated expanded requirements for climbers with little experience, the same for those so-called Sherpa Guides who lacked adequate training. But all they did was issue a strongly worded threat to all operators and climbers. Any photo that reflected negatively on Nepal, for example, lines of climbers, trash, dead bodies, or oddly, a picture of someone not on your team, well, it had to be approved by the government before sharing. There was no “or else” cited, but the implicit threat was revoking the climbing permit, deportation, and for guide companies, no future climbing permits. Operators took the threats seriously as they too had become dependent on the Everest Industrial Complex and desperately needed business after the 2020 drought.

Thus the season was set up in an atmosphere of threats and censorship not seen since the days of the Maoists or perhaps in the old Soviet Union’s politburo era. As for COVID, Nepal began reporting a dramatic decrease in new cases as 2021 started. Many felt a low level of testing was more to blame than the eradication of the virus. Less than 1% of the county of 30 million people had received a vaccine. However, with the promises of tight virus protocols by the government and operators, climbers left home telling their partners they would be safe in the pristine mountain environment. Some Nepali operators suggested that 33% of the population would receive a vaccine by the time the Everest season began.

No Way, Not This Year

Operators around the world debated if Nepal would be safe to visit. China already announced their side was closed to foreigners, and only one team of about 40 Chinese citizens would be allowed to climb on the Tibet side. After careful consideration, world-renowned guides including Alpenglow, Adventure Consultants, Adventure Global, Adventure Peaks, Jagged Globe, and Mountain Madness canceled their spring Everest Expeditions. UK travel restrictions didn’t help the companies based there. Somehow a handful of Brits went anyway, much to the ire of other Brits.

The Icefall Is Open!

The Icefall Doctors arrived in early March to establish the route through the Khumbu Icefall and up to Camp 2 in the Western Cwm. Seven Summits Treks had the contract to fix the lines from C2 to the summit. By early April, the route was into C2, and climbers were trekking to Everest Base Camp, EBC. However, something was missing, trekkers. Confusion abounded regarding quarantines. Nepal had shot itself in the foot by waiting too late to remove the barriers. Trekkers on a two-week holiday were not willing or able to spend ten days in quarantine, so they stayed home. The teahouses were empty, only filled with climbing teams—the trails, eerily quiet. The mood in the Khumbu was somber as any expected windfall from this season slowly evaporated into the thin mountain air.

First 8000er Summits!

The first summits of 2021 on an 8000-meter mountain came on Annapurna. A stunning 67 people summited, shattering any previous one-day records. Nepal-based and Sherpa-owned operator Seven Summits Treks solidified their stranglehold on the 8000ers with a simple model: overpower the mountain with many Sherpas to fix the route, break trail and guide commercial clients to the top. This model is the same they use on Everest, and now used it successfully on K2, Annapurna, and had planned for it on Dhaulagiri.

However, not everything went according to plan. The rope fixing team ran out of line above the High Camp, and the herd had to regroup and wait for a helicopter from Kathmandu to resupply the mission. After an uncomfortable night at several spots high on Annapurna, the chopper dropped off more rope, oxygen, and food. The Sherpas continued their street building to get the masses to the top. Three Russians decided to spend an extra night after going a bit too slow, so the chopper returned and got them off the peak using a long line. Meanwhile, another climber who couldn’t be bothered to descend the mountain on his own got a ride back to “town” so he could keep his appointment with Dhaulagiri.

In a blink, the face of mountaineering changed with all the gymnastics. However, a few climbed in the traditional style of small teams.

“Normal Season”

The Everest season progressed in the usual manner under fantastic weather. The notorious jet stream was on holiday south of Everest, so climbers made good use of the calm conditions to spend nights at Camp 2. A few slept at Camp 3, but most were content to tag it or ignore it, knowing they would start using supplemental oxygen at Camp 2 around 21,000-feet instead of the traditional C3, another 2,500-feet higher. This early and lower use of oxygen is another sea change on Everest today that caters to commercial clients, especially the ones lacking experience on an 8000-meter peak. I’ll touch on another, a high ratio of Sherpa support later.

MoT officials, waking up after their champaign brunch, the hangover subsidizing, must have looked at the permit numbers again and realized that 408 climbers, along with a Sherpa required for each foreigner, resulted in over 800 people potentially on the mountain. Shades of 2019 came into focus. In yet another unbelievable set of decisions demonstrating how totally out of touch they were with mountaineering, they dictated which team could climb when (in the order that they received their team permit) and a maximum of how many people could be on the mountain at one time. The operators just laughed and went about executing their plans.

On May 7, twelve Sherpas from SST reached the summit, including Kami Rita, who got his record 25 summit. The gates were open for the rest of the teams to start their summit bids.

COVID at EBC

But something else began brewing at base camp – COVID. Quiet reports emerged that helicopters, some pilots in full Haz-Mat gear, were flying climbers, and Sherpas back to Kathmandu with COVID symptoms.

When asked, the MoT had their story ready. On May 2, Rudra Singh Tamang, the Director-General of the Nepal Department of Tourism, told Climbing Magazine:

“We have not seen any reports of Covid-19 cases in base camp. There are similarities between symptoms of high altitude sickness and Covid. But there is no equipment to find out if the sickness is Covid-19. Media reports are not accurate to say that there is Covid-19 in base camp.”

Some operators, afraid of being punished, implemented a gag order on their members and posted only happy talk, further undermining any semblance of transparency. The collusion had begun and would get worse.

In nearby India, the virus exploded. Nepal, with its open border, became a magnet for the disease. Hospitals became overrun, doctors and nurses in short supply, and low supplies of life-giving oxygen served as a rallying point for global criticism. The Everest climbers became enemies of the State. Calls came from climbing organizations for all climbers in Nepal using supplemental oxygen to cancel their climbs and donate their Os to the hospitals. Falling on deaf ears, they called for the cylinders to be donated after the expeditions were over. But missed in this effort was the technical detail that the climbing canisters were small, significantly smaller than the six-foot cylinders used in hospitals. And the regulators couldn’t work with the delivery systems in hospitals. Yes, the oxygen could help a few, primarily those at home, but would not make a measurable difference with the scale of the virus’s spread. Still, these details were lost in the rage against “selfish, rich climbers from the West,” even though India and China represented the top nationality on Everest in recent years.

The mainstream press, always eager to print a negative story about Everest and the “rich westerners,” picked up on the oxygen storyline, and it went viral. At least Nepal was shown as a victim this time, much to the MoT’s pleasure, I’m sure. Sadly, the virus picked up speed throughout Nepal, and the situation became dire.

Thousands of new cases each day, hundreds dying, had created an all-out crisis – full stop. The government finally said it was out of control, and Nepalis were on their own. However, countries came to their aid. Middle Eastern countries, Spain, South Korea, the US, and even China and India began flying medical supplies to Kathmandu, including oxygen concentrators, cylinders, respirators, and more.

Norwegian Erlend Ness, the first reported case of COVID at Everest Base Camp, broke the Mot’s coverup story wide open. He wrote on his public Facebook page this look behind the scenes:

“Happy to be back home in Trondheim after a long travel from Kathmandu, Nepal. Thanks to my friends who were there and met me at arrival, I arrived last night just one day before all international flights are closed in Nepal.

For the past three weeks, I have been interviewed by TV, radio, and newspapers from all over the world. The largest Norwegian media, in particular, focused on my decision to travel against the Norwegian government’s advice not to travel abroad now. I told them that this expedition was planned for almost three years. I had hundreds of training hours and other preparations. Besides, I had not got back what I had paid for the expedition because no insurance covers. I would not have traveled for any other reason.

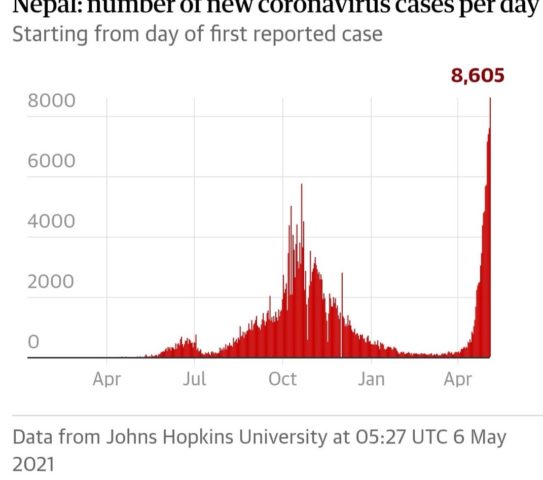

I also told that we checked the infection situation in Nepal carefully before I went down. Among other things, after a close dialogue with our Sherpas down there. The attached graph from today’s The Guardian shows that at the time we left, it looked like Nepal’s peak was in October 2020 and that it was now heading towards zero. This development was impossible to predict. Also, the fact that I was going up in the mountain a short time after arriving in Kathmandu felt safe.”

He added this graphic.

Meanwhile, over on Dhaulagiri, COVID was exploding.

Some suggested that the Annapurna climbers who took a break in Pokhara got exposed there. In the confines of base camp, the virus spread quickly. Soon over 25 people, including members of the Nepal military there to clean up trash from base camp, were evacuated to Kathmandu for COVID treatment. Again the MoT had no comment. After a few weeks, the season on this 8000er came to an end with no summits due to the devastating impact of the virus.

The strategy of denial and confusion began to take hold at EBC. Alex Txikon, who wanted to summit sans Os, ended his effort:

“Here ends # Everest2021 … We consider the expedition concluded out of a sense of responsibility due to pandemic advance. A thoughtful and consensual decision between Sendra, Iñaki, and myself after acclimating in C2 last two nights and having verified that the health situation of the entire mountain is complicated. We thank the efforts of local agencies, especially Seven Summit Treks, all the people who accompanied us, and all the friends we left at BC in this context of a global pandemic.”

No climber summited Everest in the 2021 spring season without the use of supplemental oxygen.

Nepal saw a dramatic spike in new cases and closed the international airport in Kathmandu to all foreign flights from May 6 through May 14.

China joined the censorship coverup party with one of the most confounding moves ever for mountaineering with a press release that

“China will set up ‘a line of separation’ at the summit of Mount Everest to prevent the mingling of climbers from Covid-hit Nepal and those ascending from the Tibetan side as a precautionary measure.”

A line in the snow, so to speak. A few weeks later, they canceled their entire expedition, citing virus concerns.

First Commercial Summits and Cyclone 1

Michael Fagin, a long-time Everest forecaster at Everest Weather, was the first to send the alarm of a potential cyclone in the Bay of Bengal. It was odd in that it was forming east of India. Cyclone Tauktae developed quickly and moved onshore, then turned right directly towards Everest. Fagin thought it might impact Everest around May 18. Teams hearing this moved quickly to be in a position to summit and get back down before it hit. Sure enough, on May 11, 12, and 13, over 180 people summited, including the Prince from Bahrain, who allegedly also couldn’t be bothered to walk back to base camp. He supposedly took a helicopter from Camp 2. Such are the perks of being a Prince, I suppose. He also allegedly flew to the high camps last year on Manaslu during his Everest training climb. The 12 member Bahrain team had 26 Sherpas in support.

Success was widespread with Ascent Himalaya (5 members, 11 Sherpas). Brit Kenton Cool got his 15th summit tying American Dave Hahn for the most non-Sherpa summits. Peak Promotions and more from Seven Summits Treks saw success. Climbing the Seven Summits (7 members, 10 Sherpas), Imagine Nepal (6 members, 9 Sherpas) were part of the summit parties in this period.

During this time, the US placed Nepal on the ‘do not travel list’ as the virus spread deeper. Nepal’s test positivity rate was exceptionally high at more than 40%, double India’s average. But, according to the Himalayan Times newspaper, public health experts thought it was a gross underestimation because of the limited number of tests.

Sadly, deaths were not occurring just because of COVID. As has become expected, members die on Everest. Two clients of Seven Summits Treks died. Abdul Waraich of Switzerland passed away near the South Summit, and US citizen Puwei Liu at Camp IV.’ Exhaustion’ was listed as the cause of both deaths and not COVID. If they were infected, the world would never know.

First Nepal-Side Expedition Cancels

Perhaps the bombshell of the season occurred on May 15 when Austrian-based Furtenbach Adventures canceled his entire expedition. His 20 members, four guides, and 27 Sherpas were all acclimatized, their high camps stocked with supplies for the summit push. He cited two primary reasons. First were legal issues that he and his team doctor could face for knowingly sending his customers on the summit push with the risk of injury or death magnified by COVID. The second was a moral issue that his customers made their own choices, but the Sherpas would be doing a job. He chose not to take either risk and was criticized by other teams at base camp, saying his Sherpas were widely infected and couldn’t support his customers. Furtenbach fired back that Everest Base Camp was out of control with parties, limited testing, few teams enforcing quarantines, teams intermingling, members going down valley to teahouses, and other lax protocols. He noted that his team brought “thousands of test kits,” and tested everyone frequently. However, even with all this protocol, Furtenbach had seven individuals who tested positive.

Perhaps the bombshell of the season occurred on May 15 when Austrian-based Furtenbach Adventures canceled his entire expedition. His 20 members, four guides, and 27 Sherpas were all acclimatized, their high camps stocked with supplies for the summit push. He cited two primary reasons. First were legal issues that he and his team doctor could face for knowingly sending his customers on the summit push with the risk of injury or death magnified by COVID. The second was a moral issue that his customers made their own choices, but the Sherpas would be doing a job. He chose not to take either risk and was criticized by other teams at base camp, saying his Sherpas were widely infected and couldn’t support his customers. Furtenbach fired back that Everest Base Camp was out of control with parties, limited testing, few teams enforcing quarantines, teams intermingling, members going down valley to teahouses, and other lax protocols. He noted that his team brought “thousands of test kits,” and tested everyone frequently. However, even with all this protocol, Furtenbach had seven individuals who tested positive.

Cyclones!

This drama aside, other teams stayed focused on their summit plans while monitoring the impact of the jet stream moving back north and Cyclone Tauktae’s movement. Meteorologist Chris Tomer sent a dire warning to his clients on the Nepal 8000ers, “Stand Down Immediately.” On May 18, winds and snow pummeled Everest stopping all climbing. But, more bad news emerged for this disastrous season. A second cyclone was developing—this one in the Bay of Bengal with May 25 as the target date for impacting Everest. Once again, leaders scrambled to be in position for a quick run for the summit or hunker down at base camp and hope for a late-season window. With the warming temperatures as summer approached, the Icefall was becoming more unstable to complicate matters further. The Icefall Doctors said they would stop maintaining the route and remove the ladders on May 29. The pressure to summit increased, and so did the winds.

The remanence of Cyclone Tauktae played cat and mouse with the aggressive teams. Madison Mountaineering hoped to get a jump on everyone and went to C3 only to find high winds. They were forced to spend two nights there instead of the usual one miserable night. Another meteorologist, Marc De Keyser, with weather4expeditions.com, confirmed the second cycle was forming. May 25 was the date for the newly named Cyclone Yaas. Kilian Jornet and David Goettler reportedly hoped to summit Everest via the West Ridge and then follow the ridge to Lhotse (and perhaps Nuptse) for a true traverse were caught by the weather just like everyone else. They eventually called off their attempt citing health, not weather.

Pandemic Worsens in Nepal, and at EBC

COVID continued to destroy India and Nepal, with Nepal struggling badly. The airport closure was extended to the end of the month. Foreign embassies called for their nationals to evacuate on charter flights. Spain’s charter brought much-needed medical supplies. Other countries followed suit.

It was apparent to everyone that COVID was spreading throughout base camp, but teams continue to post on social media, “Not our team. Everyone is healthy and strong.” One long-time US team bragged after the season was over for them about how smart they were, how many tests they conducted, how many summits they had, conveniently omitting how many of their team were evacuated with COVID and how many of their team refused to leave the South Col for the summit in difficult weather conditions. You see, even the best felt compelled to spin this year. These coverups changed everything on Everest. Trust is built over the years and lost in a moment.

Meanwhile, helicopters made daily evacuation flights to Kathmandu, where Sherpas and foreigners tested positive. Some stayed for a week and then returned to Base Camp; others summited with COVID but sometimes didn’t know they were sick. A Sherpa evacuated to Kathmandu with symptoms, tested positive, and received treatment. He then returned to Base Camp to summit with the Bahrain team. One member, Steve Simper, told a New Zealand newspaper that he knew something was wrong when he summited but was under obligation not to talk about it. His wife told the media, “Simper’s contract with the Canadian film company prevented him from speaking to media during the trip.”

Summit Rush

Feeling the pressure to make a summit attempt before Yaas arrived, several teams who used De Keyser’s weather forecasting spotted a “keyhole” and jumped right through it. But it came with a cost. Madison Mountaineering spent two nights at the South Col, another miserable place at 8,000-meters. In all, they spent ten days on their summit push, twice the usual time. Madison got his team up, 14 members supported by 22 Sherpas. He posted a week after summiting:

“This was no small effort, rather a hard-fought climb. Despite the many challenges this season, we remained persistent, patient, and vigilant. We climbed in poor weather, battered by high winds, and were rewarded with a day better than any I could imagine. May 23, 2021, will be a day I remember vividly, a reminder of what is possible when we remain committed, work hard, suffer a little, and put forth a great effort.

Now we are packing up our base camp and preparing to head out, as the cyclone Yaas is dumping snow on us. I’m grateful all our climbers & Sherpas are safely down off the mountain and heading home.”

Oddly, others who summited in the same timeframe talked high winds. But mountains can be funny in that way, with different conditions hundreds of meters apart through the day.

Other teams also enjoyed a victory. On May 23 – 7 Summits Club (7 members, unknown number of Sherpas – they didn’t acknowledge their help or one of their Sherpas who died, Wong Dorchi Sherpa), Pioneer Expeditions (6 members, 8 Sherpas), seven Brazilians made it along with Kaitu’s seven Chinese, one American with 9 Sherpas. Seven Summits Treks had an Indian Army team of 3 members with 4 Sherpas. Climbing the Seven Summits had three more members and four Sherpas; in addition to their earlier summits, IMG had a big night with seven members supported by 16 Sherpas. Arthur Muir, 75, with Madison scaled the peak beating the record set by another American, Bill Burke, at age 67.

Sherpa Work Program

This period saw close to 200 summits taking the season total to around 400 total, way off from the 2019 record 660 just on the Nepal side. But a closer look at the numbers reveals an interesting trend. By my count, the season ended with more Sherpas summiting than members – by far – 195 members with 339 Sherpas. We need to wait for the Himalayan Database to tally the final numbers.

There are three primary reasons for this client-support ratio. First off, remember that Nepal requires each permit holder to hire a Nepali, usually Sherpa, to “guide” them on the mountain. Today, many members are buying the ‘extra oxygen’ option. This option allows the client to climb at a higher flow rate but takes more oxygen bottles than the member and one Sherpa can carry, so another Sherpa is required. And finally, many members give up on their summit, most leave for home, but some decide not to leave from the South Col or Camp 2 for their summit bid. The Sherpas still want to summit and add the accomplishment to their resume, then parlay it into future jobs at higher pay. So the Sherpas climb for themselves and not with a client.

Now, I’m not saying this is bad and I like seeing Sherpas take interest in climbing as a sport and not purely a job. However, when people see the long lines on Everest, please remember that over half of those in line are not “rich, selfish western climbers.” Appearances can be deceiving and not always obvious.

Cancel, Climb, Hold, Run

In any event, Base Camp still had teams waiting to summit once Yaas moved on. Once again, a few went to Camp 2 to wait out the storm, but then COVID hit again. The US operator Mountain Trip outright canceled their attempt before leaving base camp, citing a shortage of Sherpas to support their members. The Climbing the Seven Summits team suddenly did the same for the same reason. Their final members would not get a chance even to try.

Two small teams, Summit Climb and Altitude Junkies, found a narrow window and tagged the summit but had to fight massive winds and snow from Yaas on the descent. Kathmandu newspapers disclosed that a 7 Summits Club’s Sherpa, Wong Dorchi Sherpa, died near the South Col from unknown causes. A few other summits occurred around May 24, including 46-year-old Chinese Zhang Hong, who became the third visually impaired person to summit Everest after American Erik Weihenmayer, at age 32, who was the first visually impaired person to summit Everest in 2001, followed by Austrian Andy Holzer, 50, in 2017.

Last Windows

By late May, when the season is usually over, several teams still hoped to get to the top. The Icefall Doctors agreed to keep the route open to the end of May, leaving May 29 and 30 as potential summit days. But Yaas held on dumping snow all over the upper mountain then onto base camp. With all of this, Alpine Ascents International, AAI, sent their team home from the South Col. They had seen enough. This decision was a telling sign from such a storied firm.

Elite Exped, Climbalaya, and Hungarian, Csaba Varga, who wanted to climb without Os, all went to Camp 2 to wait out Yaas. They were hit with high winds and deep snow but made the decision to hold, hoping the storm would ease. They targeted May 30 for Everest and the last day of the month for Lhotse.

Waiting one more day, on Monday morning, May 31, 37 people made the summit, with another 28 on June 1. The final summits came from Elite Expeditions, Pioneer Adventures, Asian Trekking, Seven Summits Treks, and 7 Summits Club. June 1 was not the latest summit on the Nepal side in history but late for modern times. May 20 and 21 are usually the days with the most summits since 2000, but it’s been a while, if ever, that two cyclones and a pandemic hit Mount Everest.

On that Monday morning, climbers reported winds at 45 mph, well over the traditional 30-35 upper limit most guides use. Some teams appeared to ignore the obvious risks of avalanche danger and frostbite from high winds and cold temperature, assuming their history of unique achievements would get them to the summit. Other’s putting their client’s safety as a priority and chose to abandon their summit dreams and return to the safety of the base camp. In the end, they were on the mountain, not us. They observed the conditions and made a judgment on behalf of their clients, some on their first high-altitude climb. It paid off, and thankfully there were no reported deaths, rescues, or frostbite. However, teams who take extra risk rarely report the downside. This has been true for decades.

Teams gave up on nabbing Lhotse for the marketing goal of an Everest-Lhotse ‘double’ with deep snow, and avalanche risk was noted as teams inspected the conditions. A very wise move that is to be commended. After all, Everest is the priority for the double. All the talk of, Everest-Lhotse traverse without Os succumbed to reality and became another regular summit of Everest, or not at all.

The season ended as the Docs pulled the ladders from the Icefall on June 3. Again by my count, 534 people stood on Everest’s summit from the Nepal side in 2021, none from the Tibet side. Four people lost their lives climbing Everest. Teams, or specifically, the Sherpas, broke down camp, collected trash with some Sherpas climbing back to C2 to collect bottles, tents, and other supplies. Most foreigners clambered into helicopters for the ride back to Kathmandu. A few made the trek back to Lukla. Yes, times have changed.

Denial Continues

Even as the season came to an end, the Nepal MoT maintained its fraud. Director of Tourism Department Mira Acharya was quoted:

“Tourists may not have to face many problems in this regard. News of the Corona spreading on Mount Everest became worldwide. After reaching the base camp, Kathmandu or some of those who fell down for adaptation may have seen the infection. No official information has been received. But the situation is not complicated by the spread of Corona in the base camp. Due to the cold, the problems seen in the base camp every year and the symptoms of Corona are similar, so it may be suspected. But due to Corona, there is no problem of rescue from the base camp. The base camp does not have a corona testing laboratory and is not easy to set up. So far no complications have been reported due to Corona.”

And some Nepali operators joined the mantra. Seven Summits Treks the largest Nepali operator for all the 8000-meter peaks and had an estimated 130 clients this year. They reported at one point to CNN they had 30 Sherpas with COVID.

“Even though the coronavirus has reached the Everest base camp, it has not made any huge effect like what is being believed outside of the mountain,” said Mingma Sherpa of Seven Summit Treks, the biggest expedition operator on Everest. “No one has really fallen seriously sick because of COVID or died like the rumors that have been spreading.”

Perhaps those who did come close to death from the virus will speak up when they get home. This blog and podcast are open to anyone who would like to present their side, either side.

I know I am a bit snarky in this summary. I own that. Also, however, I feel strongly that Nepal needs to up its game for managing its natural resources. Yes, there’s a pandemic. Yes, Nepal is overwhelmed. But there is no excuse for the blatant lies, denials, and coverups committed by the MoT this season. Do they understand that their actions only undermine the very credibility they need to effectively manage their resources? Maybe with a new government to be elected in September, there will be new roles in the MoT that will recognize what a treasure they have and manage it in a respectful, professional, and sustainable manner.

A Personal View of What’s going On?

As a climber, people ask me – why? What’s the purpose? How does standing on top of an enormous rock make the world a better place? My consistent answer for over 20 years has been climbing makes me a better version of myself, and in that sense, I can better contribute to the world. This question has never been in tighter focus than today on Mt. Everest.

The press, social media, bloggers, and, well, just about anyone who follows Everest, even from a distance, has an opinion about what happened this year. The storyline they will print is familiar. Wealthy, selfish amateurs who are oblivious there’s a pandemic and don’t give a damn if they infect the locals. All they want is their silly summit—death to them all! OK, maybe not that last part, but temperatures are running high.

With the season over, it’s the annual bash Everest season. I don’t want to bury the lead; Everest 2021 evolved into perhaps the most complicated season in history that exposes many flaws in the Everest Industrial Complex, the least of which is human judgment.

I’ve been writing about Everest 2021 since November 2020, making these same points repeatedly:

– How do you justify going knowing you run the risk of infecting the local population.

– climbers must know what they are getting into

– there is a high chance of getting sick given the compressed and intimate space at EBC

– there’s a high likelihood of not being allowed to return to your home country from Nepal if you get sick

– I was skeptical of the “bubble” theory given the cultural differences between westerners and Sherpas

– Nepal will say and do anything to get hard currency into their country, including misleading the world

– The announcement of the Nepali government censoring photos foreshadowed more censorship of bad news

– threatening guides who talked about anything negative with denial of future permits was Soviet-Esq

– at one point last year, I predicted a record year on Everest but waffled as the permits were issued slowly at first, then exploded.

And I repeatedly said both privately and publicly – wait for 2022.

It’s fair to question whether climbers should have gone at all, but again this needs to be perspective. The COVID cases in Nepal had plummeted in February and March. One could argue they stopped testing to make the numbers look good, thus attract tourists back. But in any event, the virus explosion took place well after most teams had already arrived at EBC and begun their acclimatization rotations. Yes, operators could have halted all climbing and retreated to Kathmandu, starting with the Nepali operators to help their own people. Yes, the Nepal government could have closed Everest, citing the outbreak, like China eventually did with their only national team. Yes, individual climbers could have canceled their climbs as Alex Txikon did, but he was only one of 408, perhaps a few others.

However, consider the timeline of the outbreak before determining the climber’s role. Some visitors came vaccinated. Nepal told the world they would enforce strict testing protocols before anyone could fly to the Khumbu. Nepal announced a quarantine for anyone testing positive. There were other assurances of their guest’s safety. Well, someone who invested years of training, earned valuable experience on other climbs and made a significant financial commitment might see the situation through an optimistic lens. Sadly at times, we see what we want to see.

It’s easy to sit behind a keyboard and critique others. It’s easy to say they should make different decisions. And it’s true that many mistakes have been made and continue to be made. But to place, most of the blame on the climbers feels a bit one-sided to this climber. I invite anyone who purports to report on Everest or any climbing environment to be thoughtful, considerate, assume good intentions while holding those who cross the invisible line that only the author defines, well hold them accountable, call them out.

If there is a crime that needs prosecution during any Everest season, it’s the lack of transparency. Coverups only feed the myth that Everest is easy, a walk-up for amateurs, no experience needed, and your guide will teach you everything you need to know and be there if you get in trouble, when in fact, it is difficult, deadly, and deeply rewarding. Everest notwithstanding, for anyone, get out there when it’s safe again. Mountaineering is a sport that reveals who you really are and allows you to return home a better version of yourself.

Sigh, Everest has become what everyone hoped it wouldn’t and knew it would. Nepal’s government has met every stereotype of why the governments can’t be trusted. Sadly, some climbers continue to serve as Exhibit A for those who criticize them for inexperience and dependency. Some operators gave further evidence as to why they appear to only care about being paid, and not their client’s safety. Some guide’s actions suggest that their primary interest appears to further their own reputation even at the risk of other’s well-being.

Meanwhile, there were operators and guides who made bold, courageous decisions at the risk of their own business interests. We saw individual climbers chose their future or their present. And, yes, there were some in government and Nepal climbing community who tried to call out the wrong but were ignored. As one person told me, “In Nepal, it is better to build trust and work from the inside than to shout from the outside.”

Over 500 people summited Everest this spring. Each person will return home changed. It’s up to each person to determine how they use those changes. Congratulations to all and may the lessons presented today be heeded by tomorrow’s climbers.

See who summited and the latest status on the location table.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Why this coverage?

I like to use my coverage to remind my readers that I’m just one person who loves climbing. With 37 serious climbing expeditions including four Everest trips under my belt and a summit in 2011, I use my site to share those experiences, demystify Everest each year and bring awareness to Alzheimer’s Disease. My mom, Ida Arnette, died from this disease in 2009 as have four of my aunts. It was a heartbreaking experience that I never want anyone to go through thus my ask for donations to non-profits where 100% goes to them, and nothing ever to me.

![]()

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

Thanks to all for your positive comments on my podcast this Everest season. As mountaineering news warrants, I’ll continue the casts but not as often as the past two months. Remember I update this blog more often than I post podcasts or YouTube, videos.

You can listen to #everest2021 podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Anchor, YouTube, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

11 thoughts on “Everest 2021 Season Summary: The Year Nepal Broke Everest”

Hi Alan , I just discovered your website today. I have never climbed , I am just an old retired bloke wasting his life away online, lol, anyway love your work thank you.

First of all, thank you Alan. Second, I would find a breakdown or percentage of the nationalities who summited an interesting fact.

Thank you so much for this years coverage! Just wanted to say that at least one person, Kristin Harila (Norway) did a double summit on Everest + Lhotse on the 23rd with Madison Mountaineering.

Your blog is a one stop shop for Everest late night reading. You hit the point right on the head or summit. Western hypocrisy along with Covid has hit the highest and remote part of the world. Damage control is a key marketing approach in tourism used in Time Square as well as you report in Nepal. One other thought came to mind. I remember visiting Mont San Michel in France and the visual approach to the wonder. Upon entering it I found a tourist trap with tourist menu’s, sandwich board and postcard shops. Right then I realized the way to view this wonder was from a distance. Its beauty and achievement is better absorbed form a full panoramic view. It sound to me Mount Everest has become the same. The awe is from a distance and the shock is seeing behind the skyline of the Mountain. That the ugly western world has infiltrated both achievements of natural beauty.

Thank you so much for reporting Alan! Greatly enjoyed your coverage of the season.

Thanks Alan for another years reporting, big fan of your Everest news service and tune in annually best regards, Mike.

Wow Alan! A difficult summary to write as it sounds as if was a really strange season. So well done indeed as it was all a fantastic wrap up, if somewhat complicated. I don’t understand why people still ask climbers such as you why do you want to go and stand on the top of rock. Of course one must come away a better person with a personal achievement. I still think the wonderful answer given by George Mallory is the best. “Because it’s there”. So yes, climb on! My only other comment is that surely climbing Everest also means climbing down? Not getting a helicopter if you cannot be bothered. The summit is, after all, only the half way mark.

Anyway Alan, this post was such a good read. Thank you!

I am not a climber as I can go up but am slow on way down. Find it much more difficult! But thank you I have been watching Everest posts by you for a long while now and am fascinated by it all.

Thanks for this nice summary of the season. I do somewhat disagree on one point, and which is that it is mainly the government’s fault for attracting optimistic tourists that then got trapped in a COVID hellhole.

After more than a year living with this pandemic, I think it should be absolutely obvious to anyone with a shred of common sense that no testing or quarantine regime would have saved EBC from an outbreak, especially given the limited resources available in Nepal. A single location with people flying from all over the world to meet each other for a duration of a few weeks, and with workers coming from all parts of the country to support the climbers, it basically checks every single criteria for a potential superspreader event. I think one can even ask the question: how much did the Everest season contribute to the amplitude of the wave in April/May in Nepal, and would the situation have been as catastrophic in the rest of the country if all expeditions had been scraped?

I don’t blame any of the climbers who looked at these facts during the winter/early spring, decided that after all their training, time, money and planning, they were willing to take the risk to commit to an expedition and attempt the climb despite the uncertainty and risk. It is not a choice I would have made, but I can completely understand it, and for someone that maybe can’t postpone to next year, or whose income depends on athletic achievements/sponsorships, it might well have made the most sense to push through. But as to the westerners that complain that they were caught by surprise by the sudden explosion of cases and that no one could have seen coming, that their insurance won’t cover a cancellation, or that they thought it would be safe from the pandemic up the mountain, I can’t help but wonder what planet they have been living in for the past year. Clearly it can’t have been this one.

Thanks again Alan for your brave honesty, particularly this year. The truth always outs. Don’t forget audience to please support Alan’s Alzheimer charities as his hard work and endless coverage is enjoyed by us for free.

I thoroughly enjoy your posts, this one especially. What a great summary of the 2021 season.

Comments are closed.