Heavy weather is stalling summit attempts across the Himalayas. On Everest, it’s time to test the Icefall, with the first climbers entering the Icefall for rotations to Camps 1 and 2. The Sherpas have said the Icefall is “easy” this year. Let’s look at why it takes two months to climb Everest or does it?

Big Picture

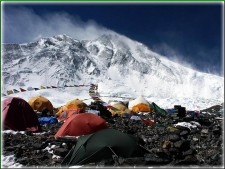

Lots of activities on Everest. Sherpas are ferrying loads to stock Camp 1 and 2 in the Western Cwm. Other Sherpas are fixing the ropes from Camp 2 to Camp 3 and beyond. They hope to reach the summit by Mayday. Members are reviewing basic skills and adjusting to Base Camp life. Several teams have completed their acclimation on Lobuche. Furtenbach Adventures reports in with :

News from our current Everest Expedition. In best weather our whole Classic Team with guide @luckydavewatson climbed Lobuche East. They arrive at Everest BC today.

Our Sherpa Team is continuing to work on Camp 2 and progress is being made with setting up the main kitchen and dining tents. This is a big job at Camp 2, and we use plenty of rope to anchor the tents in the likely event wind kicks up.

We’re going up on the hill for a few days so will be out of touch. We’ll have 2 nights at C1 (around 6,000m) and then 4 or 5 nights at C2 (around 6,400m) before coming back to EBC for a well deserved rest.

Heavy snow stalled the summit attempts on Kangchunga and Annpurna where an avalanche was reported on the route, not uncommon. On the other 8000ers, teams have just arrived at their base camps, with a few climbers already climbing.

Thus far, the season is progressing as expected. No drama, thankfully.

Weather Station Repair

In 2019, a team of Sherpas installed four weather stations at the Balcony (8,430 m), South Col (7,945 m), Camp II (6,464 m), EBC (5,315 m), and Phortse (3,810 m). Now, two have problems: at the Balcony and one at the South Col. So a team is headed up this spring to repair them. Jiban Ghimire, Pete Athans, and Dawa Yangzum Sherpa plus a Sherpa team led by Tenzing Gyalzen Sherpa form the team. source

Of course, both Athens and Dawa Yangzum are climbing legends and were part of the 21-person strong team first to install the stations. It is great to see them back on this project. A climate scientist leads the overall team from Appalachian State University, Barry Parker.

Dawa Yangzum has an impressive climbing resume with Everest, 2012, the youngest female on K2 in 2014, where we met, and the first female Nepali woman to summit the fifth highest peak Makalu. In 2021, she claimed the role of the first woman to reach the true summit of Manaslu. She is a North Face sponsored Athlete and a guide for Alpine Ascents. She also works as an instructor at the Khumbu Climbing Center in Nepal.

A bit of history, Athens has 36 Nepal Himalaya climbs to his credit, including seven Everest summits. His last was in 2002. He was part of the 1999 team, including Bill Crouse, that installed permanent GPS survey points at South Col (27,000 feet) and the highest bedrock of the mountain. In addition, they completed simultaneous GPS measurements of the summit, South Col and Kala Pattar, to see if Everest was growing taller. They also installed weather monitoring devices at various points of the mountain.

These measurements showed the summit at 29,035-feet/8850-meters. However, China and Nepal stuck to their previous measurements; China at 29,017.16-feet/8,844.43 meters underneath the snow, and Nepal at 29,028-feet/8848-meters using the top of the snow. In December 2020, China and Nepal jointly announced that they remeasured and updated the summit altitude and that both countries agreed on 8848.86-meter/ 29,031.69291-feet.

Leave No Trace

I applaud the efforts by the various Nepal Tourism departments to help clean up and keep clean the Khumbu area and mountain camps. One excellent example, with the clever name, CARRY ME BACK (CMB) Program is from the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee. They announced:

“CARRY ME BACK” – CHANGE STARTS WITH YOU! We are very excited to announce that the CARRY ME BACK (CMB) Program – a crowdsourced waste removal system to transport semi processed waste from Khumbu for proper recycling – has restarted from this week after the COVID-19 pandemic.The main aim of this program is to transport semi-processed recyclable materials, such as aluminum cans and PET bottles for recycling with voluntary support from trekkers. We have setup the pickup station at Police Check Point, Misilung near Namche Bazaar where anyone interested can pick up approximately 1 kg bag on his/her way back to Kathmandu and drop the bags at our drop off stations located near Lukla gate or Lukla airport. At the end of trekking season, Tara Air will airlift the garbage from Lukla to Kathmandu and hand it over to Blue Waste to Value for recycling.

The CMB program was initiated by Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee and Sagarmatha Next in partnership with Sagarmatha National Park, Sagarmatha National Park Buffer Zone Management Committee, खुम्बु पासाङल्हामु गाऊँ पालिका Khumbu Pasanglhamu Rural Municipality, TARA AIR and Blue waste to value.The program is sponsored by Dell Reconnect. We request all trekkers trekking in the Everest Region to participate in the CMB program – a great way to reduce your carbon footprint while trekking in the foothills of Mt. Everest.

There are other efforts ranging from individuals to commercial guided teams to the Nepal Army working this spring to clean up old trash. But, come on man, don’t leave it in the first place!

Do Your Job, Or Tells You Won’t.

The farce around Liason officers continues, onlineKhabar reports:

Department of Tourism has issued a new code of conduct for its liaison officers this season. According to this, the officials who dare to act against the code will have to face action as per the law. Hence, the department has urged them to inform the department in advance if they are unlikely to do their duties at the base camps as assigned.

To make sure that, no one skips the duty and stays away from the camp, the department says the officials shall submit pictures and videos of them with members of climbing expeditions at the base camps to the department. Likewise, they have been directed against letting climbers carry out any illicit activities during their climbing.

So they need to report that they will not show up at EBC and do their job? Will they still get their $4,000 salary? So much opportunity for Nepal to improve its mountaineering procedures.

Dhaulagiri: Back to BC

Carlos Sori, 83, Sito Carcavilla, and the six Sherpas, Mikel Sherpa, Nigma Sherpa, Nawang Sherpa, Nigma Tenjen Sherpa, Dawa Sherpa, and Dorjey Sherpa, all aborted their summit bid due to poor weather. They retreated to C1 and will descend to BC soon. Their home team posted on social media:

After seeing the weather forecasts, Carlos Soria and Sito Carcavilla have decided to go down to the CB to wait for a more favorable opportunity. They have achieved unbeatable acclimatization and all that remains is to wait patiently for the best moment to reach the summit of Dhaulagiri.

Annapurna: Waiting

Tawainese member, Grace Tseng’s home team reported in:

I received a satellite phone call from Grace yesterday. At present, the climate situation in Annapurna does not seem to be ideal. There are still an avalanche in the past few days, but don’t worry, Grace is very safe and in good condition at present. People are waiting for good weather at Camp 2. Please continue to cheer for her. Looking forward to the good news of returning to the top!

That’s all of today’s news. Now let’s take a look at why it takes weeks, if not months to climb Everest.

Everest Time

Climbers are at Base Camp to begin their climbs. It’s mid-April, and most people summit around May 19th, so what’s the hurry? Good question. Let’s look at how long it takes to get to the top of the world. I’ll look at Nepal and Tibet because after all, China will reopen one day, right?

The new shiny penny in climbing the big mountains is the so-called “speed ascents.” Known by other adjectives, let’s just call them fast or speedy but not to be confused with what Uli Steck did or Kilian Jornet does, which is real speed climbing. This new ‘fast’ is where ‘regular’ climbers hope to cut the time required to summit an 8000-meter peak by a third or even a half.

When Hall and Ball led commercial climbs on Everest in the early 1990s, the entire climb took at least two months. Fast forward to 2019, and Roxanne Vogel went from home-summit-home in two weeks climbing with Lydia Bradey and Alpenglow. Roxanne is unique and amazing.

Returning to earth, movest expeditions since 2000 will spend around 36 days on the mountain to summit. That translates to around six weeks, home to home. So when you hear about someone who summited in three days, they probably came directly from another 8,000er or several, were fully acclimatized and strong, and went from EBC to the summit directly, so it’s not a clean comparison, but it looks great for headlines!

Pre-Acclimatization: Real or Marketing for Everest Climbers?

There are mixed feelings about this as you will read. It’s becoming much more common in 2022 but had a rocky road over the past decade. For example, in a 2017 Bloomberg (a business-oriented publication) article about mountain guide and owner of Alpenglow Adrian Ballinger’s use of altitude tents, his competitors made these comments:

“Complete bloody hogwash,” says Simon Lowe, managing director of Jagged Globe, the British mountaineering company founded in 1987 and one of rapid-ascent climbing’s most vocal critics. “It’s snake oil.” Russell Brice, the 64-year-old New Zealander who runs Himalaya Expeditions, agrees, flatly discounting the tents’ safety. Guy Cotter, who runs Adventure Consultants, warned that the tents, which mimic the oxygen concentration at altitude instead of the change in air pressure, can interfere with sleep in the final weeks of training when it’s most important.”

Ballinger was mentioned in the article defending his approach:

Ballinger remains convinced that the tent works based on a trove of evidence gathered on himself. He does his own blood work during training, and he has seen a spike in red blood cells for all 15 expeditions that he’s used Hypoxico.

Another enthusiastic proponent of altitude tents is Lukas Furtenbach of Furtenbach Adventures. We’ve had many discussions about the effectiveness of the tents, and Lukas is firm, citing European study after study proving it’s real. He aggressively advertises what he calls “Flash” climbs on many mountains, including Everest, in three weeks for $108,000. This article in von bergundsteigen by Lukas is an excellent tutorial on why he has such strong beliefs.

Most of these speedy climbs are more expensive because operators want to minimize their risks by using higher oxygen flows, more experienced western guides, and a dedicated team doctor. They also bundle the price of the altitude tent into the price. Alpenglow asks for $85,000.

I did a deep look in 2014 at the use of altitude tents. While dated, it still has a lot of valid information. I asked the well-respected Dr. Peter Hackett about his views plus interviewed Brian Oestrike, then CEO of Hypoxico. You can read it at this link.

The good folks over at Uphill Athlete did their usual, deep analytical evaluation of altitude tents in 2018. The discussion was led by Steve House and included comments from Alpenglow’s doctor, Monica Pris. It’s an excellent balanced article that ends with a series of questions, most answered with “unknown.”

One more comment on altitude tents. The entire team should have used the same technique. Most operators like to run their teams in groups to leverage Sherpa and logistic resources. If one person is off-schedule, it creates problems for the leader. Ballinger requires every Everest climber to use the tents, “Pre-acclimatization using Hypoxico Altitude Training Systems. An eight-week rental is included in the expedition price, and use of the system (or equivalent pre- acclimatization) is a requirement for joining our Rapid Ascent™expeditions.”

Another factor for those using altitude tents to consider is the weather. Suppose you get delayed by heavy snow, winds, or even a typhoon. In that case, all the time you saved using an altitude tent evaporates.

To be clear, I’m not saying don’t use them, or they don’t work. On the contrary, I’ve spoken with many climbers who used these tents to say their blood chemistry did react, and they felt better upon arriving at base camp. Just, don’t assume sleeping in the tent will replace the hard work of acclimating or for some unexpected delay, won’t nullify your advantage.

Climbing Everest

With the caveat that every guide service has its own schedule, techniques, and habits, what I will describe is a broad generalization based on my six climbs on Everest and Lhotse (not all summits), two climbs in Tibet plus 20 years of following the Everest season on both sides.

Let’s break it down into six major components to climbing Everest:

- Travel to Kathmandu or Lhasa

- Travel to Base Camp

- Acclimatization Rotations

- Summit Attempt

- Travel back to Kathmandu

- Travel home

OK, here we go.

Travel from Home

The flight from home can take up to three calendar days when considering time zones and datelines. Not much you can do about that! Once in Kathmandu, most teams will take one to three days to finalize details, adjust to the new time zone and get their climbing permits. Then, those climbing from Nepal will fly to Lukla, or recently to Namache, or even higher if they used an altitude tent, to begin their trek to base camp. Most teams climbing from the north side will take a flight to Lhasa from Kathmandu.

Getting to Base Camp

Crossing into China

This short period can quickly turn into a week or two with delays for those climbing on the Tibet side. The Chinese are well known for closing the border without notice or citing a reason. So climbers are stranded until someone in Beijing changes their minds or the border manager sees the ‘lig$t.’

These closures are usually associated with fear of foreigners protesting China’s takeover of Tibet in 1950. In addition, they often coincide with anniversaries of riots, uprisings, or previous conflicts. This uncertainty is the primary reason I think climbing from the Nepal side reduces the risks, with all due respect to those who fear that side for other reasons—or flying to Lhasa and bypassing crossing the Nepal-China border.

The travel to the Chinese Base Camp on the Tibet side is relatively standard, especially when leaving from Lhasa. Climbers are driven to base camp by a representative of the Chinese Mountaineering Association (CMA). The trip usually takes about five days from Lhasa, assuming you can get there. Travel from Kathmandu is iffy, as previously discussed. Still, if possible, it requires about five days with acclimatization stops along the way.

As I opened this article, the “speed” operators who had their members sleep in altitude tents should be acclimatized to 17,000’/5200m or about the altitude of base camp. This pre-acclimatization might reduce the number of days to trek to the Nepal base camp. However, when in China, you still have to be driven by the CMA to Chinese Base Camp (CBC), but it would take two days, not the more standard five that allows for acclimatization along the way.

Trekking the Khumbu

Traveling to Everest Base Camp (EBC) on the Nepal side is a totally different story. Most people cherish the opportunity to trek the Khumbu on their way to EBC. It takes between 7 to 10 days depending on how many acclimatization nights you take (more is better). Some people will go via Gokyo using an extra few days to see this beautiful part of Nepal.

But those in a hurry will take a helicopter to reach base camp on the Nepal side. Advocates will tell members that this will keep them healthy by avoiding the teahouses and communing with trekkers in the Khumbu.

While it is true that almost everyone will get some kind of stomach bug at some point on an Everest climb, I think it’s best to get it out of the way early rather than at base camp a few days before your summit push. In my experience, 90% of ALL climbers, regardless of how they get to EBC, get some kind of GI or upper-respiratory issue. This is not a knock on hygiene, it is a fact of life when adjusting to a completely different type of food.

But more to the point, I think the trek to EBC is a highlight of any Everest climb and an opportunity to support the local economy thru porters, yak herders, teahouses, and the families who grow and sell food. Plus the scenery is some of the best on the planet!

OK, in any event, you made it to your respective base camp. Congratulations!

Acclimatization

This is the area of great change in the world of climbing. Even if you pre-acclimatize, you have to acclimatize to a higher altitude- full stop. By acclimatizing to 17,000′, you still have another 12,000’/3600m to go! Note, some claim you can acclimatize higher with the tents.

The common wisdom for those climbing on supplemental oxygen, about 97% of all Everest summiteers historically, is that you need to touch or better yet spend a night at 23,000’/7,000m. This is Camp 3 on the South and the North Col on the North.

If you are not using supplemental oxygen, then the rule of thumb is to reach 8000 meters before your summit attempt. However, in 2022, some operators put their clients on Os at Camp 2 on the Nepal side, that’s ‘only’ 21,000’/6400m, less than the summit of Aconcagua.

Nepal Side Rotations

In the “old” days ~ pre-2005~ the usual rotation looked like what I show in this animation I created:

Basically, you make four trips to ever high camps sleeping at each for one or more nights like this:

- EBC to Camp 1 to EBC

- EBC to Camp 1 to Camp 2 to EBC

- EBC to Camp 2 to Camp 3 to Camp 2 to EBC

Then the summit push.

However, today, in 2022, many expeditions will modify this schedule to limit the number of trips thru the Khumbu Icefall not only for members but more importantly for the Sherpas who have to ferry gear, food, and fuel to establish the high camps.

So some teams will use the fairly straightforward trekking peak Lobuche East, not the true summit, to adjust the body to about 20,000′ or Camp 1 on the South. This takes about a week and some teams will go to EBC then backtrack to Lobuche, others will go directly from Lukla to Lobuche.

But in the end, everyone is back at EBC and at a bare minimum will need to spend several nights at Camp 2. For example, as previously mentioned, Tim Mosedale left EBC today for “2 nights at C1 (around 6,000m) and then 4 or 5 nights at C2 (around 6,400m) before coming back to EBC for a well deserved rest.”

These two rotations take another seven days or more above EBC. If the weather turns bad, another rotation may be required before the summit push if an earlier one is cut short. Again, many teams in 2022 will cut this down to only one rotation to Camp 2, hoping to tag Camp 3.

As you can see, there is no standard formula these days!

So, in summarizing, once the team arrives at EBC, count on three to four weeks of rotations to get the body ready for the summit push. Even if you slept in an altitude tent at home for six months, this step cannot be skipped for the safest climb, in my opinion.

Tibet Side Rotations

The north side is a bit more straightforward given the absence of an Icefall to navigate. Again, in this animation, I show the typical schedule, but could be faster today:

Most teams will seek to spend a night or two at the North Col. Some will strive to reach Camp 2 at 7500 meters and those not using supplemental Os will need to get to Camp 2 or above before their summit push.

In summarizing, once the team arrives at CBC, count on three weeks of rotations, a bit shorter than the south, to get the body ready for the summit push. Even if you slept in an altitude tent at home for 6 months, like in the south, this step cannot be skipped for the safest climb, in my opinion.

Summit Attempt

Time to try to get to the top! Basically, you retrace your previous steps but go higher and higher.

South

On the south, you get back to Camp 3 where you hopefully spent a night or at least tagged 7,000-meters then move to the South Col where you spend four to eight hours before the summit push. Some teams will spend the night at the South Col before trying for the summit but this is more expensive as it requires using supplemental oxygen for almost three days, including the summit.

On the south, you get back to Camp 3 where you hopefully spent a night or at least tagged 7,000-meters then move to the South Col where you spend four to eight hours before the summit push. Some teams will spend the night at the South Col before trying for the summit but this is more expensive as it requires using supplemental oxygen for almost three days, including the summit.

Those who advocate this approach swear by it but others try to limit the time above 8000 meters as your body is in a race to death. The body no longer metabolizes food at this altitude, you lose all desire to eat and want to sleep. It is a race against time. The only way to protect yourself is with supplemental oxygen.

Most climbers will take 9 to 18 hours for the round trip climb from the South Col. My total time in 2011 at age 54 using 4 lpm of supplemental oxygen was 11 hours as follows:

- South Col – Balcony: 3:40

- Balcony (with 20-minute break) – South Summit: 2:30 hours

- South Summit (with 20-minute break)- top of Hillary Step: 1:00 hour

- Hillary Step – Summit: 30 minutes

- Descent Summit – Balcony: 2 hours

- Balcony – South Col: 1 hour

Some teams will push to get back to Camp 2 after the summit, but I can tell you from experience, that while it is absolutely safer to get lower, it is a death march towards the end. Others will stay at the South Col, but again these are the most expensive trips and usually, climbers have paid several thousand dollars for more oxygen to support the time at 8000 meters.

If you talk to 10 guides on which approach is better, you will get 15 answers. 🙂

North

On the north, you start higher than on the south giving you the advantage of a shorter summit night, but the winds and temperature can be brutal and cold. Usually, the summit bid starts from Camp 3 as follows:

On the north, you start higher than on the south giving you the advantage of a shorter summit night, but the winds and temperature can be brutal and cold. Usually, the summit bid starts from Camp 3 as follows:

- Camp 3: 27,390′ – 8300m – 4 to 6 hours

- Yellow Band

- First Step: 27890′ – 8500m

- Mushroom Rock -28047′ / 8549m – 2 hours from C3

- Second Step: 28140′ – 8577m – 1 hour or less

- Third Step: 28500′ – 8690m – 1 to 2 hours

- Summit Pyramid – 2 hours

- Summit: 29,035′ / 8850m – 1 hour

- Return to Camp 3: 7 -8 hours

Most climbers will try to get back to ABC after their summit, spend the night and then return to CBC the next day.

Travel Back to Kathmandu

On both sides, you end up back at your respective base camp and will be shocked at how fast you are pushed to leave. Remember that time is money and that each meal, day, and support costs the operator money, so they try to get their members out of camp as fast as possible on the road home.

These days, many south side climbers pay $1,000 to $3,000 for a helicopter out of EBC to Lukla or even Kathmandu bypassing the trek out. A big mistake in my opinion as the trek out is the time to let your experience sink in, regardless of the result. It is a time to decompress and enjoy the Khumbu and consider your next step in climbing.

On the north, you jump in a Toyota 4Runner and get driven back to the nearest airport or border. Not very ceremonial but you have no choice.

Back in Kathmandu, most people spend a few days visiting the bars while rearranging flights. I promise you that the chances of flying on the reservation you made months ago are slim to none unless you are willing to stay in Kathmandu for days or over a week, which is not a bad idea! But this is why all guides will suggest you get a changeable ticket for your return. Once you are back in Kathmandu, you are no longer under their responsibility.

Again, in summary, this part can take a day, a week, or a month.

Bottom Line

This is what the typical schedule is for both sides:

| South | |

|

South Climb Schedule

|

Elevations and Times Between South Camps

|

See my breakdown of a Nepal climb at this link

| NORTH | |

|

North Climb Schedule

|

Elevations and Times Between North Camps

|

See my breakdown of a Northside climb at this link.

Summary

OK, we looked at the parts so let’s put it all together (if you are still with me!)

| South (days) | North (days) | |

| Travel to Kathmandu or Lhasa | 3 | 3 |

| Travel to Base Camp | 7 – 10 | 2 – 5 |

| Acclimatization Rotations | 20 – 28 | 20 – 28 |

| Summit Attempt | 7 | 5 |

| Travel back to Kathmandu or Lhasa | 3 | 2 |

| Travel Home | 2 | 2 |

| Range | 42 – 53 | 34 – 45 |

Can it be done faster? You bet. Professional athletes, those with gifted VO2 Max, or those with unusual ambitions can significantly cut some of these times (I’m sure we will hear from them in the comments!) But for the typical Everest climber who wants to be safe and take no shortcuts, these numbers are what you can expect.

The Flight Home

Similar to the flight over, you can be home in a day or two. But while flying hone, let it all sink in, relax, sleep and celebrate the fact that you did something many dreams of and few actually attempt. Congratulations on taking the chance, making the investment, and doing your best.

Nepal 2022 Permit Update

The permits for Everest have picked up as expected, but I’m not anticipating a significant further increase. I’m anticipating between 250 and 300 total foreign permits issued for Everest. 2021 was a record year with 408 permits issued to foreigners. There have been 800 total permits issued for 23 peaks thus far. These permits have generated $3.5M in royalties for the government. Almost all of this revenue stays in Kathmandu, with some in various personal pockets and none to the Sherpas, porters, or other high-altitude workers. The Nepal Ministry of Tourism posted these foreign permit tally as of April 19, 2022:

- Everest: 287 on 35 teams (25-30 teams with between 250-300 members expected)

- Ama Dablam: 82 on 8 teams

- Annapurna I: 26 on 4 teams

- Annapurna 4: 9 on 1 team

- Baruntse: 20 on 3 teams

- Bhemdang: 8 on 1 team

- Dhaulagiri: 27 on 3 teams

- Gangapurna: 2 on 1 team

- Himlung: 35 on 4 teams

- Khangchung: 67 on 6 teams

- Kangchung/UIAA: 2 on 1 teams

- Lhotse: 94 on 10 teams

- Makalu: 39 on 4 teams

- Manaslu: 9 on 1 team

- Mukot: 4 on 1 team

- Norbu Khang: 5 on 1 team

- Nuptse: 53 on 6 teams

- Phu Khang: 5 on 1 team

- Pokhar Kang: 9 on 1 team

- Saribung: 3 on 1 team

- Saula: 2 on 1 team

- Thapa (Dhampus): 10 on 3 teams

- Urknmang: 2 on 1 team

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2022 podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Summit Coach

If you dream of climbing mountains but are not sure how to start or reach your next level from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers throughout the world achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 25 years of high altitude mountain experience, including summits of Everest, K2, and Manaslu, and 30 years as a business executive.

4 thoughts on “Everest 2022: How Fast Can You Climb Everest?”

Ich wünsche auch, dass Bewohner des Himalaya ihr Können auf internationaler Ebene zeigen und messen können (und damit genauso viel Geld verdienen könnten..) Zum Beispiel mit Jost Kobiusch David Göttlerder on the way ist.Aber das ist nicht alles. Ich möchte wissen, was die Sherpa-Community über solche Personen denkt, abseits vom kommerziellen Geschäft…!!!

I don’t think the SHepras view Jost and others as a threat when they have hundreds upon hundreds of clients who need their help. They only gets upset when they feel a lack of respect as they did in 2013. P.S.Why do you use fake names?

Here’s a dumb question but, aren’t the Sherpa rope fixing teams the first to summit each year?

Almost always. Pre-1990ish, Sherpas didn’t go to the summit often and National teams usually fixed the ropes, but today.

Comments are closed.