Welcome to Everest 2024. The season begins soon, and I’ve already posted several Everest 2024 big-picture updates for this season:

- Everest 2024: Welcome to Everest 2024 Coverage – an introduction to the Everest 2024 Spring season.

- How Much Does it Cost to Climb Everest: 2024 Edition – My annual review of what it costs to climb Everest, solo, unsupported and guided.

- Everest by the Numbers: 2024 Edition – A deep dive into Everest statistics as compiled by the Himalayan Database

- Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2024 Edition – A detailed look at Everest’s routes, commercial, standard and non-standard.

2024 will be my 22nd season of all things Everest: 16 times providing coverage, another four seasons of actually climbing on Everest, and two years attempting Lhotse.

I summited Everest on May 21, 2011, and have climbed it three other times (all from Nepal) – 2002, 2003, and 2008, each time reaching just below the Balcony around 27,500′ (8400 meters) before health, weather or my judgment caused me to turn back. I attempted Lhotse in 2015 and 2016. When not climbing, I cover the Everest season from my home in Colorado as I did in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023 and now the 2024 season.

For those who closely follow Everest, the official release of the summit numbers is always a milestone. The Himalayan Database (HDB) updated the latest summit statistics in December 2024. I’ve been digging into the stats and found some interesting trends and trivia.

The Himalayan Database

The HDB, now a free download from their site, contains the climbing records for almost all Nepal and Tibetan Himalayan peaks from 1905 to the present day. However, they recently changed their model, as Richard Salisbury and Billi Bierling recently told me:

With the ever-increasing number of people attempting the commercial normal routes on the eight 8,000m peaks in Nepal, it is no longer possible for the team to interview every single climber or expedition leader. For this reason, we have decided that – exactly 60 years after Miss Elizabeth Hawley met her first team – to concentrate on new and interesting routes on the 8,000ers and other commercial peaks as well as new and technically challenging mountains that are climbed in Alpine style in the Nepal Himalaya. The Ministry of Culture, Tourism & Civil Aviation, Nepal, will continue to provide us with the numbers of climbers who attempt commercial mountains, which we will enter into the Himalayan Database. However, we are happy to meet everyone who contacts us and would like to tell us about their expedition.We also welcome any hints and corrections to our data as the truth deserves to be told, just like Miss Elizabeth Hawley emphasized in her career.

You can always check in and register to tell us about your climb online. For further information, visit https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/registerwu or scan the QR code above.

The legendary Ms. Elizabeth Hawley passed away in 2018 at age 94. See this fantastic video interview of her, this interview with Richard, and my podcast with Billi.

Here are a few words on terminology before we get into this. The HDB uses the term ‘hired’ for anyone paid to support an expedition. So ‘hired’ includes Sherpas, Tibetans, porters, and guides. In addition, several ethnicities support the Everest ecosystem, including Tamang, Magars, Rai, and others. And on the north, there are Chinese and Tibetan workers. Some articles refer to these as mountain workers or high-altitude workers.

The term “member” usually refers to someone paying a guide to help them with their climb. I use the words members and foreigners and Westerners interchangeably with members, acknowledging that climbers from S. Korea, for example, do not consider themselves “Westerners.”

Preparing for Everest is More than Training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are not sure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers throughout the world achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountain experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

The Big Picture

I suspect 2024 will be another busy year. First, there is the insatiable lure of Everest, and, as is the standard since 2013, droves of inexperienced climbers drawn in by “no-experienced required” low-cost operators. However, 2024 will be different, with the north side open to foreigners and the last year before Nepal raises their permit price by 36% to $15,000.

I expect 800 total summits from both sides this spring, comprising at least 150 on the Tibet total (members plus hired) and well over 650 on the Nepal side. Even with these numbers, the totals will still lag the pre-pandemic record set in 2019 of 877 total summits, comprising 661 from Nepal and 216 from Tibet. Last year, 2023, saw 655 total summits from Nepal and thirteen on Tibet. Let’s break all of this down and see what our climbers can expect.

The headlines for 2024 include that Everest summits are growing and death rates are reducing from the record of eighteen in 2023. As I summarized in “How Much Does it Cost to Climb Mt. Everest-2024 edition“ with this bottom line:

We’ll see what 2024 brings, but history suggests it will be a big year, especially with the North open and prices increasing. The bottom line is that Nepal will be more crowded than ever, so guides will need to coordinate schedules. We can expect six to eight deaths on the Nepal side and one on the Tibet side.

Stepping back to review the overall numbers, 6,664 different people have summited Everest for 11,996 summits, and 327 people have died attempting Everest on all routes. Nepal remains the more popular and deadly side. Sherpas now dominate with a majority of summits.

Deaths from 1922 to 2023

| NEPAL | TIBET | TOTAL | ||

| Members | 3,919 | 1,980 | 5,899 | 49% |

| Hired | 4,431 | 1,666 | 6,097 | 51% |

| TOTAL Summits | 8,350 | 3,646 | 11,996 | |

| 69% | 31% | |||

| Member Deaths | 114 | 86 | 200 | 61% |

| Hired Deaths | 103 | 24 | 127 | 39% |

| TOTAL Deaths | 217 | 110 | 327 | 2.7% |

| 64% | 36% | |||

| Death Rate | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.12 |

Note that two events on the Nepal side represented 21% of the total hired deaths. There were 17 deaths in 2014 when a serac let loose onto the Khumbu Icefall, and 10 more died in 2015 when an earthquake created an avalanche that hit Everest Base Camp.

Follow the 2024 Everest Coverage!

2023 Recap – Records Deaths and Brutal Cold

The 2023 Everest spring season ended with some records to take pride in and others to be avoided. If there were one word to summarize the season, it would be chaotic or perhaps deadly. This spring was the deadliest season in Everest’s history. It was also brutally cold.

Nepal issued a record 478 climbing permits to foreigners. Add in one and a half Sherpa supporting each foreigner; over 1,200 people pursued the summit last spring. Fears were rampant of a 2019 repeat with long lines and deaths. The lines never developed, thanks in part to colder weather that sent a higher number of climbers home in mid-season, many with a persistent virus. However, the deaths did develop, but not because of the record permits or climate change.

There were around 667 summits on the Nepal side and 16 from Tibet, which was still closed to foreigners. More Sherpas, 378, summited than clients, 277, according to the Himalayan Database. Only 55% of the members who went above Base Camp, 483, summited, 277. There was an all-time Everest high of 18 deaths – 6 Sherpas and 12 clients. In my estimation, 11 deaths were preventable.

What stole the headlines were the daily reports of rescues, frostbite, missing climbers, and deaths. The root cause of the chaos remains elusive and, in some cases, covered up. Some blame the record permit numbers, inexperienced clients, and low-cost operators. However, Nepal government officials cited climate change. Blaming climate change is a red herring to abdicate responsibility by operators and authorities. Again, in my estimation, 11 of the 18 deaths were preventable.

Continue reading about Everest 2023

By the Numbers

More Summits, More Deaths

Everest has an immutable attraction that is oddly perverse. When there is a record number of deaths, the next season has more climbers than the previous deadly one. For example:

- 2006: 11 deaths, 494 summits

- 2007: 7 deaths, 634 summits

- 2012: 10 deaths, 581 summits

- 2013: 8 deaths, 684 summits

- 2014*: 16 deaths, 134 summits

- 2016: 5 deaths, 679 summits

- 2023: 18 deaths, 668 summits

- 2024: ? Deaths, ? summits

* 2014 season ended early when 16 Sherpas died in Icefall. 2015 closed because of the earthquake.

We’ll see what 2024 brings, but history suggests it will be a big year, especially with the North open and prices increasing. The bottom line is that it is more crowded than ever, so guides will need to coordinate schedules more tightly than ever.

Since 1953, there have been 11,996 summits of Everest through January 2024, on all routes, by 6,664 different people. Climbing from the Nepal side is the most popular side and has a higher death total and death rate with 8,350 summits with 217 deaths through January 2024 or 2.6%, a rate of 1.14. The Tibet side has seen 3,646 summits with 110 deaths through January 2024 or 3.0%, a rate of 1.08.

For those not using supplemental oxygen from Nepal, 130 died, or 60% of the total deaths or a rate of 1.01% for those making a summit attempt. On the Tibet side, for those not using supplemental oxygen, 48 died, or 44% of the total deaths or a rate of 0.75% for those making a summit attempt. Tibet-side climbers tend to be more experienced, thus accounting for fewer deaths.

Note that the death rates are for all hired support and members, including those at base camp, not just those who summited.

The last time Everest saw no summits on either side was in 1974.

Tibet or Nepal Side?

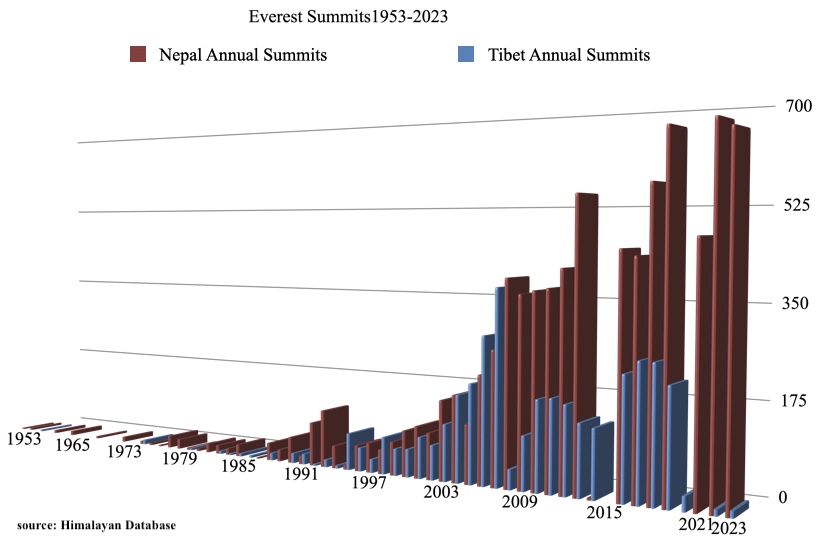

Before 2008, Tibet was gaining in popularity. In 2000, Nepal had 62% of the total climbing traffic compared to Tibet’s 32%. However, by 2007, the gap had closed, with Nepal at 60% and Tibet at 40%. Then came 2008, when the Chinese effectively closed Everest to take the Olympic torch to the summit. This event caused many in the climbing community to not risk their money with the Chinese. Many operators moved to the Nepal side, some for good. China’s closure of Everest to foreigners from 2020 through 2023, citing COVID, exacerbated this trend.

Russell Brice, a mainstay on the north from 1994 to 2007, putting 219 people on the summit, including 53 in 2007, switched to the south after the 2008 closure on the north, contributing to the stall on that side. Brice sold his company, Himalayan Experience, a few years ago. The comeback for Tibet has been slow but steady but may never reach the pre-2008 days because China puts a member cap of 300 per season while Nepal continues to have no limit.

Natural Disasters and Rising Fees

The avalanche and ensuing Sherpa strike of 2014 and the 2015 earthquake sent some people back to the Chinese side; however, it appears these events had little impact on climbing from either side and were viewed as a natural disaster not unique to either side.

One wildcard that may impact the growth on the Chinese side is the permit fee. An Everest climbing permit from the Chinese (Northside) is now between $15,800 and $18,000 per person for a team permit of 4 or more. Nepal will raise its permit fee from $11,000 to $15,000 in 2025, so we will see if China raises theirs more. The days of climbing Everest for a few thousand dollars are over.

Deaths Ticking Back Up

Overall, 317 people, 217 members, and 110 hired (Sherpas) died on Everest from 1921 to 2023. An average of 4 people have died each year since the first attempt in 1922. From 2010 to 2023, deaths doubled to an average of 8 annually. The 31 total Sherpa deaths in 2014 from the serac release onto the Icefall and the 2015 earthquake drove up the average death rate, as did the record 2023 deaths of 18. All of these deaths were on the Nepal side of the mountain.

Digging deeper into each period, the death rate from 1921 to 1999 was 1.80, with 170 people dying, 100 members, and 70 hired. More members died than hired due to pioneering new routes and the Sherpas being used primarily for load carrying.

When commercialization grew in the early 2000s, the death rate drastically declined from 1.80 to 0.80. There were fewer new routes, and most of the traffic took place on the Southeast or Northeast Ridges led by Western Guide companies like Adventure Consultants, Jagged Globe, or International Mountain Guides, and today by Nepali companies like Asian Trekking, 8K Expeditions and Seven Summits Treks. From 2000 to 2023, 157 people died, a death rate of 0.80, but more members, 100, still died more than Sherpas, 57.

The reduction in overall deaths is primarily because of significantly higher Sherpa support ratios, improved supplemental oxygen at higher flow rates (up to 8 lpm), improved gear, weather forecasting, and more people climbing with commercial operations.

This good news of fewer deaths (1921-199:170 compared to 2000-2023:157) came as the total number of people climbing Everest took off. The number of people above Base Camp almost doubled in the past 23 years – 19,610 (9,353 members with 10,257 support) compared to the previous 80 years. From 1921 to 1999 – 10,916 (5,773 members with 5,143 support) people went above BC.

However, death statistics show that on both sides, on all routes, descending from the summit is significantly more deadly for members, with 55 deaths descending, compared to 15 ascending on the Nepal side and 48 descending with 11 ascending on the Tibet side.

Of the 8000-meter peaks, Everest has the highest absolute number of deaths (member and hired) at 327 but ranks near the bottom with a death rate of 1.11. Annapurna is the most deadly 8000er, with one death for about every fifteen summits (73:476) or a 3.76 death rate. Cho Oyu is the safest, with 4,044 summits and 52 deaths or a death rate of 0.40, with Lhotse next at 0.38. Of note, 79 Everest member climbers, out of 200 members, died descending from the summit, or 39%. K2’s death rate has fallen dramatically from the historic 1:4 to around 1:8, primarily because of more commercial expeditions with huge Sherpa support ratios.

However, it’s still critical to select your guide as I cover in Everest 2019: Season Summary The Year Everest Broke, eight of the 11 deaths were climbing with operators charging under the median price.

While the Nepal side’s safety reputation eroded after the tragic 2014, 2015 and 2023 deaths, the Tibet side has also had multiple deaths. In 2004 and 2006, six and eight people died, respectively. The last year when there was commercial climbing, there were no deaths on the Tibet side, which was 2016, and on the Nepal side, 2010. 1981 was the last time Everest saw no deaths on either side.

Note that the HDB calculates the death rate by taking the number of people above base camp who died, not just those who summited.

Standard-98% vs. Non-Standard Routes-2%

An interesting bit of trivia is that through January 2024, of the 11,996 summits, only 249 (185 members and 64 hired) took a “non-standard” route, not the Southeast Ridge or Northeast Ridge. There were 84 (54 members and 30 hired) deaths on these climbs–34% of the total deaths, which partly explains why the standard routes are most popular with commercial operators–lower risks. The countries with the most summits on the non-standard routes are Nepal (67), Japan (26), the USA (27), S. Korea (23), the USSR (23), and Russia (16.)

As this chart shows, climbing the standard routes accounts for 73% of the deaths, with the Southeast Ridge dominating all deaths at 175 or 52%. This number is heavily driven by the 2023 record of eighteen deaths and the 2014 ice serac release off the West Shoulder of Everest onto the Khumbu Icefall, taking 17 lives. Also, 14 people died at Basecamp in 2015 after a 7.8 magnitude earthquake caused an avalanche off the Pumori-Lintgren ridgeline. Whether these were one-time events or ongoing concerns has yet to be determined. Therefore, climbers must make their own decisions as to the safer standard route.

Here is the summary update with 2023 statistics:

|

Reason |

Northeast Ridge |

Southeast Ridge |

Other Routes South |

Other Routes North |

total |

|

Avalanche |

7 |

40 |

15 |

16 |

78 |

|

Fall |

18 |

31 |

18 |

8 |

75 |

|

AMS |

12 |

29 |

0 |

5 |

46 |

|

Exposure/Frostbite |

10 |

6 |

6 |

4 |

26 |

|

Illness (non-AMS) |

5 |

18 |

2 |

1 |

26 |

|

Exhaustion |

12 |

15 |

0 |

1 |

28 |

|

Icefall Collapse |

0 |

16 |

3 |

0 |

19 |

|

Crevasse |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

Disappearance |

4 |

5 |

0 |

3 |

18 |

|

other/unknown |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

7 |

|

Falling Rock/Ice |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Total |

71 |

175 |

45 |

39 |

336 |

|

% of Total |

21% |

52% |

13% |

12% |

The last team to complete a new route was a Korean team on the Southwest Face in 2009. In 2019, Cory Richards and Esteban “Topo” Mena made a valiant attempt to send a 6,551-foot direct line in a couloir, a narrow rock gully, on the Northeast face of Everest. The gully joins a high ridge and continues to a steep face and onto the summit. The route began just above Advanced Base Camp at 21,325 feet on the Tibet side of Everest. Eventually, they turned back at around 7,600 meters due to “conditions we encountered coupled with our chosen tactics compounded by exertion.” after spending 40 hours on the wall with one open bivvy.

Oxygen and Summits and Deaths

It is rare to summit Everest without using supplemental oxygen; only 221 people have ever done so. Digging deep into the data reveals that of the 327 deaths, 178 were not using O’s when they perished, but this is a bit misleading because, for many of the deaths, 105 were doing route preparation, primarily by Sherpas. Most would not have used Os because they were low on the mountain. A case in point was the 2014 ice serac release and the 2015 earthquake that killed 31 people, and they were below Camp 1 and not using oxygen.

Looking at climbing in modern times, i.e., from 2000 to 2023, we can see that 88 members (not Sherpas) summited without supplemental oxygen, and 28 died, or 32%. This rate compares with the 4,832 members who summited with Os, and 60 died or 1.2%. In other words, you are 26 times more likely to die if you don’t use supplemental oxygen.

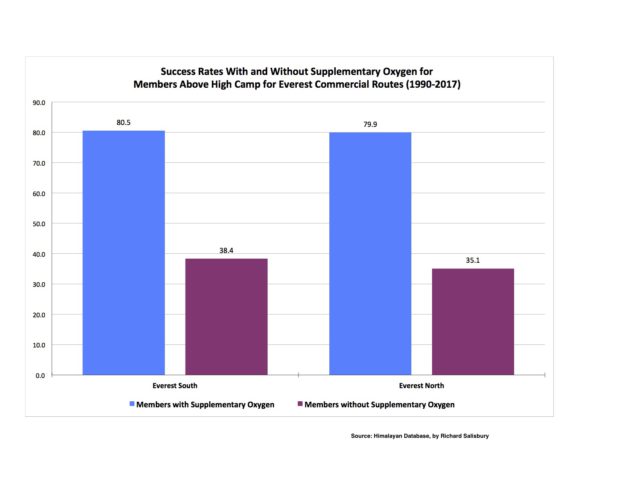

Back in 2018, I reached out to the HDB’s Richard Salisbury to help analyze the impact of supplemental oxygen both in terms of summits and deaths. He ran a few reports for success rates with and without supplemental oxygen for members above base camp on the standard commercial routes. The results were what we would expect – those climbing on O’s had fewer deaths and better summit results. This chart shows that climbers who use supplemental oxygen have almost twice the summit success as those who shun O’s.

This chart shows that climbers who do not use supplemental oxygen have almost three times the death rate than those who shun O’s, but the numbers are pretty low, with only 11 total members dying on their summit bid.

Looking at the north side and why climbers turn back on their summit bid above High Camp, bad weather is the primary reason for both those who use and don’t use O’s. But for those who don’t use O’s, frostbite and cold rank as the second-highest reason, while those who are using Os claim exhaustion as the second most common reason to turn back.

Looking at the north side and why climbers turn back on their summit bid above High Camp, bad weather is the primary reason for both those who use and don’t use O’s. But for those who don’t use O’s, frostbite and cold rank as the second-highest reason, while those who are using Os claim exhaustion as the second most common reason to turn back.

The primary benefit of using supplemental oxygen is warmth. When exposed to extreme cold, the body will divert blood flow to the brain and organs and sacrifice extremities. Os is a safety net for hands and feet.

The north side of Everest is notoriously colder and windier than the south. These conditions may explain why more climbers not using O’s turned back – a sign of wanting to live! Interestingly, 2017 was an exception, with just the opposite characteristics on the south side when high winds pummeled climbers, stopping several no-Os’ attempts.

Looking at the south side and why climbers turn back on their summit bid above High Camp, lousy weather again is the primary reason for both those who use and don’t use O’s. But for those who don’t use O’s, frostbite and cold, along with exhaustion, rank as the second-highest reason to turn back.

Looking at the south side and why climbers turn back on their summit bid above High Camp, lousy weather again is the primary reason for both those who use and don’t use O’s. But for those who don’t use O’s, frostbite and cold, along with exhaustion, rank as the second-highest reason to turn back.

Using supplemental oxygen is always controversial, bringing up ethics and style. I know for some people, this is a red hot subject. However, in 2024, most operators will provide 2, 3, 4, or even 8 liters per minute to their clients at some points during the expedition. One operator is even offering a climb to Camp 2, no summit, with supplemental oxygen and a personal Sherpa!

Sherpa Support and Summits

Over the last 15 years, Everest has seen explosive growth in the number of Sherpas summiting. Commercial operators used to have a ratio of 1 Sherpa to 5 members, but today, 2 Sherpas for each member is common. This extra support need is driven by more inexperienced members, offloading more gear to Sherpas, higher oxygen flow rate, thus more bottles required, and high-end guides who market that there will always be a Sherpa climbing by your side.

In 1992, when commercialization began on the south side, 22 Sherpa and 65 members summited or a ratio of 0.34 members to hired. In 2010, 196 Sherpas with 175 members summited or 1.12. Looking at the Tibet side, it is even more dramatic. In 2000, the ratio was 17:38 or 0.45 hired to members compared to 106:110 or 1.04 in 2019 (the last full year on the Tibet side).

In 2023, on the Nepal side, it was a whopping 1.36. In other words, for every member who summited, 1.36 Sherpas did as well. In 2022, it was a staggering 1:1.62, with 415 Sherpas summiting with 256 clients on the Nepal side. Today, more Sherpas and Tibetans have summited Everest than paying clients, 5,721 vs. 5,620. As this chart shows, the support ratio trend is increasing on the Nepal side.

The 2008 dip in the chart for Tibet was when China closed the mountain for the Olympics, and there were no foreign climbs from 2019 – 2023.

Everest – An Insatiable Allure

As the previous discussion shows, the number of summits has increased since 1992 when Adventure Consultants Rob Hall and Gary Ball guided four paying members to the summit, the beginning of widespread commercialization. David Breashears guided Dick Bass in 1985 and gets credit for starting the entire industry of commercializing Everest.

Even with significant price increases, Everest still draws a crowd each year. Over the past ten years, companies with Western guides on the Nepal side have increased their average prices from $64,000 to $71,500 today, while Nepali guides have gone from $35,000 to $45,000 but are often heavily discounted by up to 25%. On the Tibet side, prices have exploded from $32,750 to $75,000, mostly driven by Western teams marketing “rapid/flash/speed” programs that require more support than the traditional schedule.

Interest in mountaineering rose steadily after the 1996 disaster when 15 people died. The drop-off in summits in 2008 was when the Chinese closed the north side for the Beijing Olympics, effectively stalling momentum on that side. Two more years caused significant disruptions in climbing the peak when, in 2014, a Sherpa strike closed the Nepal side, and in 2015, the earthquake stopped all summits on both sides. And, of course, COVID has disrupted climbing in 2020 through 2023 on the Tibet side and just in 2020 on Nepal, who refused to close the mountain and give up any revenue. But it is good to understand that after each of those ‘bad’ years, the following year results in record summits. So it seems that bad news only increases the allure of climbing Everest, like bugs to bright light.

Everest Trivia

In the trivia department, the Himalayan Database shows

- One true solo ascent Messner, 1980 North

- 35 traverses

- 22 ski/snowboard descents

- 13 Parapente (paragliding) descents

- 15 disputed ascents

- 14 unrecognized ascents

Fun Facts

I have a section on my main website called Everest for KiDs. It is based on my 2002 attempt at Everest, where I did not summit, and today, schools around the world use it to teach students about goal setting, geography, and Everest. Part of that section contains these fun facts:

Everest Facts for KiDs

Geography

- Everest is 29,031.69-feet or 8848.86-meters high

- The summit is the border of Nepal to the south and China or Tibet on the north

- It is over 60 million years old

- Everest was formed by the movement of the Indian tectonic plate pushing up and against the Asian plate

- Everest grows by about a quarter of an inch (0.25″) every year

- It consists of different types of shale, limestone and marble rock

- The rocky summit is covered with deep snow all year long

Weather

- The Jet Stream sits on top of Everest almost all year long

- The wind can blow over 200 mph

- The temperature can be -80F (-62C)

- In mid-May each year, the jet stream moves north, causing the winds to calm and temperatures to warm enough for people to try to summit. This is called the ‘summit window’. There is a similar period each fall in November.

- It can also be very hot, with temperatures over 100F (38C)in the Western Cwm, an area climbers go through to reach the summit.

History

- Like all mountains around the world, the local indigenous people were the first to see it.

- Everest is called Chomolungma (Jomolangma) by the Tibetan people. It means mother goddess of the universe.

- The Nepal Government named Everest, Sagarmatha. It means goddess of the sky.

- It was first identified for the Western world by a British survey team led by Sir George Everest in 1841.

- Everest was first named Peak 15 and measured at 29,002 feet in 1856.

- In 1865, it was named Mount Everest, after Sir George Everest.

- In 1955, the height was adjusted to 29,028 feet.

- China uses 29,015 feet

- In 2020, using GPS technology and a joint measurement by Nepal and China showed 29,031.69 feet (8,848.86 m). Both countries use this now.

Summits – updated January 2024

Early Attempts and Summits

- The first attempt was in 1921 by a British expedition from the north (Tibet) side

- The first summit was on May 29, 1953, by Sir Edmund Hillary from New Zealand and Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa from Nepal. They climbed from the south side on a British expedition led by Colonel John Hunt.

- Tenzing Norgay had assisted Swiss Everest expeditions in previous years.

- The first north side summit was on May 25, 1960, by Nawang Gombu (Tibetan) and Chinese climbers Chu Yin-Hau and Wang Fu-zhou.

- The youngest person to summit is American Jordan Romero, age 13 years 11 months, on May 23, 2010, from the north side.

- The oldest person to summit is Japanese Miura Yiuchiro, age 80, on May 23, 2013

- The first climbers to summit Everest without bottled oxygen were Italian Reinhold Messner and Peter Habler in 1978

- Reinhold Messner is the only person to have truly summited Everest solo and without supplemental oxygen. He did it in 1980 from the Tibet side via the Great Couloir.

Male Summits

- The youngest male to the summit is American Jordan Romero, age 13 years 10 months, on May 23, 2010, from the north side.

- The oldest male to the summit is Japanese Miura Yiuchiro, age 80, on May 23, 2013

- Kami Rita (Topke) Sherpa (Thami) holds the record for most summits (male or female) with 29, the most recent one in May 2023.

- Pasang Dawa Sherpa of Pangboche has summited 27 times with the last on May, 2023.

- Apa Sherpa (Thami Og), Phurba Tashi Sherpa (Khumjung) are next with 21 summits each. Both are now retired.

- Briton Kenton Cool has the most non-Sherpa summits with 17, the most recent in 2023.

Female Summits

- The first woman to summit Everest was Junko Tabei of Japan in 1975

- The oldest woman to summit was Japanese Tamae Watanabe, age 73, in 2012 from the north

- The youngest woman to summit was Indian Malavath Poorna, 13 years 11 months, on May 25, 2014, from the north side

- 883 women have summited through December 2022

- Nepali Lakpa Sherpani, 48, holds the women’s summit record with ten (3 South, 7 North)

Summit Statistics

- There have been 11,996 summits of Everest through January 2024, on all routes, by 6,664 different people.

- 5,899 members (clients) have summited, and 6,097 have been hired (Sherpas)

- 883 females have summited.

- 1,571 people have summited multiple times

- The Nepal side is more popular, with 7,695 summits compared to 3,646 summits from the Tibet side

- 224 climbers summited without supplemental oxygen through January 2043, about 1.9%

- 35 climbers have traversed from one side to the other.

- 681 climbers have summited from both Nepal and Tibet

- 155 climbers have summited more than once in a single season, including 78 who summited within seven days of their first summit that season.

- About 62% of all expeditions put at least one member on the summit

- Member climbers from the USA have the most country member summits at 906

- Sherpas have the most summits at 6,097

Death Statistics

- 327 people have died on Everest from 1922 to January 2024. This is about 2.7% of those who summited or a death rate of 1.11 of those who attempted to make the summit.

- 199 Westerners and 110 Sherpas died on Everest from 1922 to January 2024.

- Westerners die at a higher rate, 1.38, compared to hired at 0.87.

- Of the deaths, 178 died attempting to summit without using supplemental oxygen.

- 14 women have died, for a death rate of 0.81 compared to 1.14 for male climbers.

- Of the 327 deaths, 92 died on the descent from their summit bid or 2.8%

- The Nepalese side has seen 8,350 summits with 217 deaths through January 2024 or 2.8%, a rate of 1.14. 130 died not using Os, or 3.5%.

- The Tibet side has seen 3,646 summits with 110 deaths through January 2024 or 3.0%, a rate of 1.11. 48 died not using Os, or 1.3%.

- Climbers from the UK and Japan have the most all-time deaths at 17

- Most bodies are still on the mountain, but China has removed many bodies from sight.

- The top causes of death on both sides were avalanches (77), falls (75), altitude sickness (45), and exposure (26).

- From 1922 to 1999, 170 people died on Everest, with 1,170 summits or 14.5%. But the deaths drastically declined from 2000 to 2023, with 10,826 summits and 157 deaths or 1.4%.

- However, four years skewed the death rates, with 17 in 2014, 14 in 2015, 11 in 2019, and the record 18 in 2023.

- At least 11 of the 2023 deaths were preventable through better logistics, adequate oxygen and better on-mountain support.

- The reduction in deaths is primarily because of higher levels of Sherpa support, supplemental oxygen at higher rates, better gear, weather forecasting, and more people climbing with commercial operations.

Latest: Spring 2023

- In 2023, there were 667 summits, including only 12 from Tibet, as it was closed.

- Three summited not using supplemental oxygen.

- A record 18 Everest climbers died.

- 57% of all attempts by members were successful.

- 61 Females summited.

Climbing

- There are 18 different climbing routes on Everest.

- It takes 39 days on the normal schedule to climb Mt. Everest in order for the body to adjust to the high altitude.

- Some climbers summit in two weeks by pre-acclimatizing in machines at home.

- There is 66% less oxygen in each breath on the summit of Everest than at sea level.

- Thin nylon ropes attached to the mountainside are used to keep climbers from falling.

- Climbers wear spikes on their boots called crampons.

- They also use ice axes to help stop a fall.

- Thick, puffy suits filled with goose feathers keep climbers warm.

- Most climbers eat a lot of rice and noodles for food.

- Almost all climbers use bottled oxygen because it is so high. It helps keep the climbers warm.

- Climbers use bottled oxygen starting at 26,000 feet, but it only makes a 3,000-foot difference in how they feel, so at 27,000 feet, they feel like they are at 24,000 feet.

- Nepal requires you to be 16 or older to climb from their side and between 18 and 60 on the Chinese side.

Sherpas

- Sherpa is the name of a people. They mostly live in eastern Nepal. They migrated from Tibet over the last several hundred years

- Sherpa is also used as a last name

- Usually, their first name is the day of the week they were born. Nyima – Sunday

- Dawa – Monday

- Mingma – Tuesday

- Lhakpa – Wednesday

- Phurba – Thursday

- Pasang – Friday

- Pemba – Saturday

- Sherpas are hired by climbers to guide, carry tents and cook food at the high camps

- Sherpas climb Everest as a job to support their families

- Sherpas can get sick from altitude like anyone but are stronger at altitude than foreigners.

- Sherpas feel it is disrespectful to stand literally on the tippy top since that is where Miyolangsangma, the Tibetan Goddess of Mountains, lives.

Trivia

- Babu Chiri Sherpa spent the night at the summit in 1999

- Kami Rita (Topke) Sherpa (Thami) holds the record for most summits (male or female) with 29, the most recent one in 2023

- Over 33,000 feet of fixed rope is used each year to set the South Col route

- You have to be at least 16 to climb Everest from the south side and 18 from the north

- Climbers burn over 10,000 calories each climbing day, double that on the summit climb

- Climbers will lose 10 to 20 lbs during the expedition

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Preparing for Everest is more than training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are not sure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers throughout the world achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountain experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

Everest Pictures and Video

© All images owned and copyrighted by Alan Arnette unless noted. Unauthorized use and reproduction are strictly prohibited without specific permission.

A tour of Everest Base Camp 2016

Comments are closed.