Everest 2016 was a success by many measures. Climbers achieved life long dreams and a country got a break. It was a ‘normal’ season with around 600 summits but sadly there were five deaths plus one on Lhotse. However in stark contrast to the previous four years on Everest, 2016 lacked large scale tragedy or extreme drama.

If ever a poor country needed a break, it was Nepal in early 2016. The ‘business’ of Mount Everest means more than foreigners trying to summit the world’s highest mountain. It means pride, jobs, a future for the next generation and obviously, money.

This is my annual season summary that includes my own reporting while I was attempting Lhotse this year, excerpts from climber’s and guide’s blogs, my own interviews at base camp and after their climbs. Plus I add my own personal opinions on some topics. Visit this page to see the results of all the team I could track. This is a long post, so get your favorite beverage and let it all sink in.

Tough Few Years

By now the last two years of Everest, and Nepal, is well known. In 2014 an ice serac released off the West Shoulder of Everest killing 16 Sherpas in the Khumbu Icefall, 19 in total that year. The season ended immediately with no legitimate summits on the South side.

In 2015 a huge earthquake struck near Kathmandu and killed 9,000 Nepalis, mostly in the poorest rural areas. 19 lives were lost after the earthquake triggered an avalanche onto Everest Base Camp. The season ended immediately on both sides with zero summits – not that it mattered in the grand scheme.

While the world was eager to help Nepal rebuild, an inept government was trying to establish a constitution and failed to give aid those citizens who needed it the most. But those in the Solo Khumbu area of Nepal, mostly ethnic Sherpas, rebuilt their teahouses and homes and called for the world to return.

Trekkers Stay Away, Climbers Take the Deal

As the Everest climbing season approached, early reports showed that permit numbers were down, and down a lot. At the last minute Nepal’s Ministry of Tourism approved an extension of the climbing permits ($11,000 for Everest) that were issued in 2015. They would be good for 2016 and 2017.

This was a late attempt to keep the business of Everest alive. They made a similar decision for the 2014 permits, also at the last minute in 2015 but extended those for five years, thru 2019, similar to what China had already approved for both years. 265 Everest climbers just from 2015 on the Nepal side now had their permits extended.

I’m not sure these measures mattered as Everest seems to attract more climbers after a tragic year. The years following the largest death tolls to date in 1996, 2006 and 2014/15 were followed by a record number of climbers. The more Everest takes lives, the more people come.

But in any event, Climbers reacted quickly in 2016. By early April there were 34 teams at Everest Base Camp with 289 Everest permits issued, compared to 319 in 2015 or down about 10%. Even with the last minute approval, 69 climbers were reported to have used their previous permits. 500 High Altitude Workers were shown on permits to support the foreign climbers or almost 1.7 for each member.

78 permits were issued for Lhotse and 44 for Nuptse permits. The non-Everest permits are a bit misleading as anyone who wants to enter the Icefall or just go to Camp 2 needs a permit for that maximum altitude but may have no intention of trying to climb that mountain.

The Everest business is estimated to generate about $15 million for the Nepal economy and in 2015 with the permit extensions royalties were reduced to $1.6m. In 2014, tourism accounted for 8.9 percent of Nepal’s GDP and 7.5 percent of its total employment.

But trekkers stayed away, there were 40% less trekkers than in the previous year hurting hotels, restaurants, and taxis in Kathmandu. The teahouses, guides and porters throughout the trekking areas of Nepal also saw a dramatic decline in business. Trekking brings more money to Nepal than climbing, so the backlash from bad publicity around the earthquake and embargo was hurting.

Unusually Warm

The climbing season began with a mixture of optimism and apprehension. The impact of the earthquake was an unknown on the upper part of Everest. Only one climber attempted it in the autumn of 2015 and climbed a bit above Camp 3 on the Lhotse Face. He said the route was the same as in previous years.

As climbers trekked to the Nepal Everest Base Camp (EBC), they noticed the teahouses were almost empty, the temperatures were warm. I was there. I was part of the migration to EBC aiming to summit Lhotse, thwarted by the earthquake last year.

Those focusing on climbing from the Tibet side were met with the usual unexplained delays by the Chinese government, knowing they would eventually get to enter but just not sure when they would arrive at the Chinese Base Camp (CBC).

On the South, EBC spread out for over a mile at the foot of the Khumbu Icefall, some camps were in the exact same position as the ones destroyed by the avalanche only 12 months earlier. Climbers spoke in hushed voices about the warm temperatures and the risk of another avalanche. Guides assured their members that everything was fine.

By the time Everest Base Camp began to fill up, it was obvious that something was quite different, at least at this altitude. In early April, EBC is usually frozen solid, but in 2016 it was already melting like it was late May or even early June. A river of running water flowed freely thru base camp. The only ones who benefited were the water crews.

The big question was the condition of the upper mountain – Lhotse Face, Triangular Face and the route from the South Summit to the summit itself – all speculation until humans set foot on those areas.

Khumbu Icefall

With warm temperatures, the Icefall Doctors worked hard to set the route to Camp 2 but were delayed by difficulties in Icefall. The instability encouraged them to go slowly, carefully trying to avoid the tragedies of the past few years.

They found a creative route and instead of the normal 20 ladders in the Icefall, 2016 only had about 7 in the beginning. Sections of the route were challenging, more so than in any of my five previous climbs.

At the top of the Icefall was a near vertical 100 foot/30m ice and snow wall that served as the final gateway into the Western Cwm. Early in the season there was no ladder so both Sherpas and members got backed up, many struggeling to get off the ground and began climbing. For some, they simply gave up and said they couldn’t do it until helpful hands gave them a fanny push to start their climb.

Over on the North, the Chinese/Tibetan team responsible for fixing the ropes were slowed by high winds. It seemed there was a tale of two mountain – warm down low, and windy and cold up high. In fact this would be how the season unfolded.

On the Nepal side, commercial teams finally entered the Icefall on April 11, actually about normal for Everest. And on the North, climbers finally started arriving at CBC around April 17, again about normal for Everest.

Always Connected

On the Nepal side, EverestLink provided fairly reliable Internet connection throughout the entire season. Over on the North, China Mobile offered 4G. And satellite connection using Thuraya or Iridium competed the ability for anyone, almost anywhere to post their latest selfie, Snapchat clips, tweets, posts and more.

Multiple virtual reality or 360 degree camera set-ups caught almost every moment and there were nine camera crews just on the south side and several on the north to capture sponsored and hi-profile teams. Mamut already posted their video from EBC to the summit.

On the south, the film crews were invasive and honestly, a pain. They felt like ambulance chasers showing up at the moment a climber had a problem, camera in their face, release in hand hoping to capture “reality” for the next series on Discovery or the Travel Channel. Climbers wanting to go low profile had to turn away to avoid the spotlight, others relished being on camera and readily told their story.

Teams began to enter the Western Cwm and Advanced Base Camp on the North for their acclimatization rotations. Some broadcasted their every move via social media including real time interviews and chats. While new for many, this ‘real-time’ coverage was pioneered in the 1990’s on the site, MountainZone.

Widespread Illness

Everest Base Camp began to feel more like an airport than a climbing base. With clear skies, every morning brought a flock of choppers to EBC, many to pick up climbers and a few trekkers with health issues. It felt early to be having so many evacuations but this was the tip of the iceberg.

From my perspective, there seemed to be many cases of upper repository infections that simply wouldn’t go away – I know I was one of them! Several people developed HAPE early on their rotations.

A ‘Normal Season’ Develops

With teams now in place on both sides of the mountain, the season progressed with little to no problems. I wrote on April 26 that it was looking like a normal season:

“So just would a normal season look like at this point? Well, based on history we will get a few days of bad weather – snow and wind – that will shut down the mountain. Everyone will hunker down in their tents and wait for it to pass.

The ropes will reach the summit around May 10th thus opening the flood gates for the aggressive teams to make their summit pushes. Most will have issues due to cold temps and high winds but we will see early summits. There may be a death.

By the time the summit attempts begin in earnest, the 287 people with Everest permits will have attrited by 20% making about 230 people on the mountain with an equal number of Sherpas.

The majority of the Everest summits will occur after the first push. The largest teams, IMG, Seven Summits Treks and the Indian Army will spread out their attempts. The smaller teams will weave into the mix.

If this warm weather and high pressure remains in place, there should be between 8 and 12 suitable summit days with low enough winds to summit. Spreading the remaining climbers out across these days will mean little if any crowding or bottlenecks at the usual suspects – Lhotse Face, Yellow Band, Southeast Ridge, Hillary Step, etc.

The season will wind down around May 25 on the south while going strong on the North into early June.

If all this happens, it will be a quiet season and one many have longed for.”

I was close on almost all my predictions but the North side started late and ended early. But overall, the normal season continued.

Where are the Ropes?

Today’s climbers and guides have become accustomed to having a fixed rope from base camp to summit not only to mark the route but also to provide a safety net in case of a fall.

Many teams will not climb where there are no fixed ropes thus the climbing schedules are driven by how quickly the ropes get “fixed”. Setting these lines is dangerous, difficult and physically demanding work.

Almost every commercial team and independent climber depends on other people to set the fixed ropes. On the North, it is done by the Chinese run CTMA (China Tibet Mountaineering Association) who go to the summit and on the Nepal side by the Nepal run SPCC (Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee) aka the Icefall Doctors; but they only work to Camp 2 and at that point a loose collation of commercial guide companies pay their Sherpas to continue to set the line to the summit.

Teams on the South began to get anxious as the ropes were only set to Camp 2 by mid April, and over on the North, climbers began voicing their complaints. But long time climbers and operators called for calm as patience is required to climb these big beasts.

Sherpa Safety Progress

With EBC filled with new Nepali based guide companies, and the long time western ones, the traditional leaders on the South – Himex, IMG and others did their usual task of coordinating the fixed line from Camp 2 to the summit but after years of lobbying, something dramatic changed.

The Nepal government finally gave permission to use helicopters to ferry the summit ropes and gear from Gorak Shep to Camp 1 in the Western Cwm thereby eliminating 88 Sherpa loads thru the Icefall – a genuine sign that the Nepal government cared about the lives of the Sherpas. One individual deserved credit for this, Damber Parajuli, leader of the Expedition Operators Association.

This was a huge break thru that hopefully will continue in future years.

Rescue

Only two of the 289 permits were for a route other than the normal Southeast ridge on the Nepal side. Slovak alpinists Vladimír Štrba and Zoltán Pál were to attempt the rarely climbed Southwest face via the British Route, without supplemental oxygen.

As they were climbing after a few days of heavy snow, they got caught in an avalanche and became trapped on the Face and one of the climbers had an eye injury.

Four Sherpas from Seven Summits Treks conducted a rescue that involved setting a new fixed line 700 meters long above 7,000 meters that allowed the climbers to move to a safer location. Eventually they were helicoptered out from camp 2.

Summit Ropes and First 2016 Summits

On May 11, about on schedule for the Nepal side, a team of nine Sherpas made the climb from the South Col to the summit, fixing the rope along the way.

Then on May 12th, the UK’s Kenton Cool got his 12th summit while guiding member Robert Richard Lucas. Sherpa Guides Pemba Bhote and Dorchi Gyalzen summited with them. 13 minutes later, Mexican climber David Liano Gonzalez and Pasang Rita Sherpa also summited. This was Liano’s fifth summit.

The next day, 13 May, targeting a very short weather window, climbers from Himalayan Experience (Himex), Jagged Globe and Asian Trekking pushed thru to put 25 people on the summit.

The conditions were not ideal. Jagged Globe‘s David Hamilton, a very experienced Everest guide, posted an excellent recap of their summit on 13 May. This paragraph captures it all:

“At approximately 07.15 we reached the South Summit just as the winds rose to 30 knots plus. This was accompanied by blowing snow and visibility of less than 50m. I was strongly of the view that continuing to climb upwards in these conditions was unacceptably dangerous and aimed to cancel the ascent. I consulted with the two most experienced Sherpa guides with the team (Pem Chhiri and Nima Gyalzen) and they suggested resting in a small hollow just below the South Summit for a short while to see if conditions would improve. I was skeptical of this, as I feared that the wind strength would increase.”

For the next four days, someone summited Everest from the Nepal side – a record for consecutive summits days- six in all – however, none from the Tibet side, yet. But then the winds came for real.

May 19 and 20 and Frostbite and …

The winds blew and blew on both sides. Teams on the Nepal side pushed to the South Col understanding that the winds were forecasted to 50 mph according to one veteran Everest weather forecaster. The teams wanted to beat the crowds but paid a price.

When they arrived at the Col, tents were being ripped apart. The winds were so high, some teams could not even set up their tents. Wisely, everyone took shelter where they could and settled in for a long night and an unexpected extra day at almost 8000 meters.

Alpine Ascents posted this update. It is their standard program to spend a night at the South Col before heading to the summit.

“ climbers and sherpas team arrived south col 26000 feet at 2.00 pm. It was very challenging day for them with strong wind approximately 45 mile per hour, but ours team keep continues and and able to pulled thru.the challenging part was setting tent at 26000 feet with blowing hard. team did not gave up they wait several hours and able set tents, got hot fluid and foods. every one is doing well and in great spirit, they are all laying in their warm sleeping bags. The plane for tomorrow is rest day. Right know it starting to snowing and wind still blowing hard. hoping to calm down soon.”

Other climbers were not so optimistic. Robert Kay with Altitude Junkies sent out these messages:

- I’m at Camp 4, worst weather ever

- My climb is over. I’ve never suffered like this. 2 big days to get to base camp then relax & warm!

- We r wet and cold with wind up to 85 mph. I’m in a 3man tent with 3 Sherpa. No sleep tonight.

But just like that, the winds did calm down the evening of 20 May and people left the South Col for the summit. With the 19th climbers queued up along with the 20th teams, a large crowd developed. There were over 200 climbers above 8000 meters that night.

One large team moving slowly and not willing to step aside created the feared line of climbers up the Triangular Face between the South Col and the Balcony.

Climbers went slowly – too slow, using up their limited oxygen at a rate faster than planned. Fingers and toes became cold. Summits were attained but the cost was high – over 20 cases of frostbite were ed, some climbers required helicopter evacuations to Kathmandu to save appendages. Those at base camp said ‘Everest Airport’ was busy.

One climbers with a smaller team told me that seven of their eight members suffered frostbite.

Why Frostbite?

Frostbite in modern times is, in general, a rare occurrence but does happen. Modern high altitude boots, with the proper fit, down gloves and full down suit along with full balaclava and google that cover the face eliminate exposing bare skin to deadly wind chills.

Generous oxygen running at 4lpm with efficient masks provide sufficient support to keep the core warm and blood flowing to the extremities.

Why so many people suffered frostbite is a mystery. Perhaps their gear was not as good as it could have been, perhaps they had old technology oxygen systems, maybe they took gloves off to manipulate anchor points and didn’t cover their faces properly when the winds picked up.

Perhaps the lack of mountain experience showed it unforgiving face for some this year. If they were climbing slow – for whatever reason, maybe they might have been better served by turning around.

But some suffered as they worked to save others. The photo to the right is of a climber who almost lost his toes while working with a teammate to save his life. These brave cases are almost never seen by the general public.

courtesy of David Liano

Where is the Hillary Step?

A few days after these summits, David Liano set the Everest climbing community abuzz with a Facebook post suggesting the 2015 earthquake had moved the rocks on the Hillary Step and it was now a snow slope.

I consulted with multiple operators and Sherpas who have collectively over 100 Everest summits and had been on the Hillary Step after David. They felt the rocks had not collapsed and it appeared dramatically different due to an unusual amount of snow.

Later in conversations with 2016 summiteers, they said the Step was a simple snow slope that looked nothing like the pictures for previous years.

It may be next year if the snow blows away that the real shape of the Step will be known.

Nepal Summits Continue

After the first wave of six consecutive days, a quick break then more summits in wicked weather, the final summit pushes occurred on the Nepal side in an orderly manner from May 22 thru May 24. They were rewarded with great weather, for Everest, and over 150 more summits in about 3 days.

IMG put 46 climbers on the summit. Seven Summits Treks guided 5 female members from the Indian NCC Girls Expedition plus another four Indian members. They also provided logistics and Sherpas for the Chinese team with a total of 36 people of the summit.

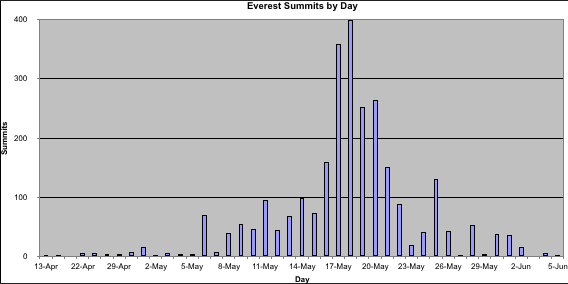

This chart shows the historical summit day and 2016 was very close to historical averages.

Visit this page to see the results of all the team I could track.

Summits on the North

As the Nepal side racked up summit after summit – albeit many in harsh weather where teams took amazing risks, the Tibet teams took advantage of marginal conditions during an early summit windows to follow the Tibetan rope fixers to the summit.

There were several wounded US military veterans who summited that I’ll list them later. Overall 20 climbers were attempting Everest not using supplemental oxygen, 11 climbers from the Tibet side, only 5 were successful in their goal.

But the perennial team of 7 Summits Club lead the numbers with 27 on top followed by Summit Climb (27), Adventure Peaks (6), Satori (12), Kobler & Partner (5+) and others.

It is always hard to get exact information from that side because for whatever reason, they just don’t provide information. Visit this page to see the results of all the team I could track.

I have a complete summary of the season from Tibet in this post.

While Everest was seeing multiple summits on both sides, Lhotse, the world’s 4th highest peak, was conspicuously absent.

On 19 May Ang Furba Sherpa (also reported as Ang Phurba Sherpa) died while fixing ropes for climbers on Lhotse. The details have never been reported but whether he depended on an old weak rope or wasn’t clipped into the safety line, regardless he fell 2,000m/6,500feet down the Lhotse Face beside a line of climbers and some at Camp 3, to his death.

The Indian Army and a team from Dreamers Destination were following the Arun rope fixers. Interviews with those climbers show a great dissatisfaction with the rope fixing process including not enough ropes, using old ropes and late efforts.

About 78 climbers had Lhotse permits but most were for Everest climbers wanting to bag Lhotse after their Everest summit, something often planned and rarely accomplished.

Once the death occurred, those who summited Everest on the 19th cancelled their plans. While citing respect, the difficult weather, extensive frostbite and just the physical challenge of doing back to back 8000er perhaps set in.

Other teams had dedicated Lhotse climbers, including myself with Altitude Junkies. I detailed in this post on why I left but the short story was a serve upper respiratory infection that required a helicopter evacuation from Camp 2 to Kathmandu.

After Ang Furba’s death, feelings were mixed to fix the ropes on Lhotse and several teams felt it was possible and some were rumored to have attempted it, including a Japanese team, but for the third year in a row, Lhotse saw no summits.

Tragic Deaths

Since 2000, there have been 82 deaths with an average (and median) of a total of seven deaths each season combined on both sides. Using the arbitrary measure of summits to deaths, from 2000 to 2013 the ratio is 1.85%, for 2016 it dropped to 0.8%. In the 1990’s the median ratio was 5.6%. From the early 1920 to today it is about 4%.

Even though 2016 would go into the record books as one of the safer recent years, the deaths stirred up another huge reaction by the media around the world as the deaths were viewed as preventable and not from a natural disaster like an earthquake or avalanche.

Historically, most Everest deaths could have been prevented if the climber had proper mountain experience, showed personal responsibility, climbed with using proper support for their skills, used adequate oxygen and their guides/Sherpas/teammates took fast and appropriate steps once the climber was in trouble.

update : Charles MacAdams died at Chinese Base Camp after reaching his goal of the North Col source

This spring season, three deaths occurred with one team. A South Korean expedition lead by Korean climber Jinchol Cha and supported by Trekking Camp Nepal “lost track” of four Indian climbers – Subash Pal, Paresh Chandra Nath and Goutam Ghosh. Three were found dead and one survived and was evacuated to Kathmandu.

Two additional deaths occurred with another team. Dr Maria (Marissa) Elizabeth Strydom and Eric Arnold both climbing under the leadership of Arnold Coster/Seven Summits Treks deaths brought focus onto the Everest guiding world.

Poor Communications

In the Strydom death, with limited information, the media began to place blame on Coster for slow reaction, inadequate support and squarely placing their deaths on his shoulders. Headlines and interviews were brutal.

The storyline followed a familiar path – the climber signaled their problems with both words and going slower and slower, the Sherpas gave aid with extra oxygen and drugs, the climbers got to a lower camp and in spite of attention succumbed to their condition.

Communications between families and members was insensitive at with the Stardom family reading of their daughter’s death from a Kathmandu newspaper report posted on the Internet.

A tragic situation became a public debate as Coster issued a statement on Facebook explaining everything that could be done was done. His statement included this about Strydom:

Marisa was doing well until the “Balcony”, but became very slow after this and decided to turn around on the South Summit at 8am in the morning. Normally this would give her enough time to descent safely, but her condition deteriorated rapidly. Halfway between the South Summit and Balcony she was hardly able to move and became very confused. Her Husband and several Sherpa’s struggled all night to bring her down and miraculously she made it back to the South Col 2am that night, after spending 31 hours above the camp. We managed to stabilize her that night with Medicine & Oxygen and Marisa was able to walk out off the tent herself the next morning. Helicopter rescue is only possible from Camp 3, so we continued our descent the next morning. Marisa was able to walk herself, but 2 hours out off camp she collapsed on the “Geneva Spur”. Her Husband tried to retrieve her, but this was not possible anymore. Rob was evacuated by helicopter from Camp 2 the next day and is in Kathmandu now.

The mother of Strydom, Maritha Strydom used Facebook and the media to ask questions about acclimatization, oxygen, rescue resources and the competency of Coster. Maritha Strydom posted these questions to Coster’s statement:

This is the first substantial information regarding my daughter, Marisa Strydom’s death. As we guessed, it seems like she was in the death zone for an exceptional period of time. I hope to also find out exactly what happened with her while everyone else was moving on for their summit push:

The Delorme, in reach satellite phone she carried for 7 weeks, had a button, which would activate Global rescue, this never happened.

From 6.03 am Friday 20 May, Australian Eastern Standard time, till late Saterday afternoon 21 May, that’s around 30 plus hours later, the pings stopped and only picked up late Saturday afternoon above camp4.

Other questions haunting us:

How swiftly was she moved down to lower altitude?

How and who monitored her and how was she cared for?

Why was Global rescue ( which she took membership insurance out before she left) never contacted. We all know altitude sickness is deadly and an emergency. Global rescue is still waiting for that call.

How was she diagnosed and ed?

We got a message the previous night that they had a massive push and were spent.

What kind of evaluation was done on each climber’s health and abilities that night

There is a massive time gap that is not covered in any explanation so far between where Marisa fell ill and the next ping. The satellite pings indicated an overstay at high altitude.

How were the climbers evaluated at each camp for possible altitude sickness?

At approximately 10 pm Saterday night, almost 40 hours after Marisa turned around, The Himalayan Times reported that she passed away 11 minutes earlier. How did they know that soon?

Marisa and Rob climbed Denali twice the previous two years and summited. They climbed many high peaks, including Aconcagua . They’ve been climbing the past 12 years. They were both super fit and healthy.

Something went terribly wrong.

There’s also questions regarding the skipping of the Camp 3 stay over, during acclimatisation and the speed they moved up before the summit push, amongst other questions.

Something must be done to regulate the whole operation of expeditions. Some deaths are unnecessary.

At present there’s no legislation to force expeditions to care for casualties before pushing to summit, it is a free for all operation once a permit is obtained.

Numbers should be managed, so bottlenecks are prevented and operators should be rated according to climbers health and safety on a yearly basis, operators should also be qualified and regulated, also in mountaineering first aid and emergency procedures.

Sherpas should not only get a bonus if their member summit, but also if they get a sick climber down safe.

Protocols need to be put in place to make climbing safer and regulate the circus.

I hope the two parties are talking now but do not know. Three of the five bodies were removed at extraordinary effort by a team of over 13 Sherpas who climbed back to the South Col to carry them back to Camp 2 for helicopter transportation to Kathmandu. It’s unclear if Strydom’s Global Rescue policy covered her recovery and return but Australian press reports the family is trying to raise $30,000 for the recovery and return.

Two of the Indian climbers remain at the South Col and hopefully will be recovered next spring.

I did an in-depth look at Why People Die on Everest baed on these situations.

Impressive Life Saving Actions

At the other end of these tragic stories were few of these ‘good’ stories are made public. The climber themselves or teammates worked quickly to help someone in trouble.

Robert Kay, with Altitude Junkies pushed hard to summit, his third attempt. On the way down he developed HAPE and HACE. A guide from another team said he felt Kay was moments from death. But thanks to him and Kay’s teammates they quickly administered oxygen and drugs and monitored him thru a long night at the South Col.

Kay posted a dramatic report on his website about his summit and subsequent problems. An excerpt:

Once it became clear that I would not be covering the last 100 yards under my own power, six people hoisted me up and dragged me like a dead man to my tent and rather unceremoniously tossed me inside. At some point during this process Ben and Laura Darlington reached me. They are a young couple from Canberra, Australia and are part of our small Altitude Junkies team. They immediately saw the gravity of the situation and were actively getting out the dexamethasone (Dex) injection that Phil had given to all of us in base camp. Ben is an electrician and Laura is an accountant – just normal people, not medical professionals. But they are smart and capable and knew exactly what needed to happen.

Just as they were preparing to administer the first injection in their life, Billy Nugent appeared. He is a professional guide with Madison Mountaineering and although not a doctor, he does have more training and experience than any of our team has. He later confided with Ben that he believed I would be dead within a few minutes. Billy and Laura crawled in after me, pulled my coats and shirts off my shoulder and I was rapidly injected with the powerful steroid. The results are pretty immediate and significant and it was a bit like coming back from the dead. I was still far from capable of doing anything to save myself, but I wasn’t going to die in the next handful of seconds.

Over on the North, an independent climber self diagnosed his own HAPE and wisely reed from his summit push barely avoiding death. US Climber Alexander Barber was doing an independent attempt with as little support as possible – no Os, Sherpa and climbing ‘alone’ as much as that is ever possible on Everest these days.

This impressively strong, young climber was making excellent progress, and showing good judgement as when to push and when to wait. But as he began his final upper mountain summit push, he developed HAPE and almost lost his life.

He posted on his blog about understating the extent of his illness to keep his father from worrying

… I had full on HAPE, and nearly died the nights of the 23rd and 24th. It was an incredibly long 4 days – and a hell of a battle – to get down the mountain.

In reality on the 23rd I wasn’t sure I would survive the night – as crazy as that is to hear myself say. I knew I could count on little help getting down the mountain, so it was self-rescue or perish. I had promised my father that follow-up text when I arrived at Camp 1 from Camp 3. But I couldn’t find it in myself to break the news to him. So I lied. I was in midst of a struggle for my life. At the time, I didn’t know what exactly was wrong, but I knew I was deep in it and I suspected it was HAPE. Once I did get down to C1, and the next day when I got down to Advanced Base Camp, many people went far out of their way to help me. I probably owe my life to those kindhearted care givers.

Alex wanted to acknowledge that Zeb Blais brought O2 to C1 and helped him down from C1 to ABC.

Another inspiring story was of British climber, Leslie Binns who met a climber in trouble descending from the Balcony. Brinns gave her his extra oxygen bottle and cared for her thru the night. Why Indian climber, Sunita Hazra. was alone is another story. The details are at this link.

There are other stories this year of climbers giving up their summits to help someone in need.

The key lesson in all of these cases was knowledge and tools to perform life saving actions. As I have said for years, climbing Everest or any mountain is all about personal responsibility and not pushing it when you are in trouble and climbing with trusted experienced partners so that in the event of a sudden issue, everyone knows what to do.

Summits with a Story

Every summit had a story but here are some caught the media’s attention:

- Kenton Cool with his 12 summit, UK record

- Greg Paul with two artificial knees

- Colin O’Brady summited and went on to set a Grand Slam record

- Sri Lanka first summit Jayanthi Kuru-Uthumpaala

- Lhapka Sherpa new female summit redid at 7

- Melissa Arnot for most American female summits

- Melissa Arnot first female American no Os summit to survive

- Alyssa Aza youngest Australian at 19

- Marin Minamiya youngest Japanese at 19

- Irini Halay first Ukrainian female on Everest

- Nick Talbot first with cystic fibrosis

- USMC Ssgt. Charlie Linville wounded US military

- Chad Jukes wounded US military

- 2nd Lt. Harold Earls active duty (not wounded, full health )US military

- Army Capt. Elyse Ping Medvigy active duty (not wounded, full health))US military

What Went Right?

In wrapping up, a lot went right this year:

- Over 300 ‘foreigners’ summited accomplishing life long dreams – this cannot be underestimated

- Over 500 Sherpas and Nepalis got work earning significant income for their families

- The Country of Nepal generated millions in royalties and associated tourism income

- There were no Everest climber deaths on the Tibet side

- Five people summited without supplemental oxygen adding them to the 2.7% club

- Sherpas and foreigners worked well together

- Most of the teams on the Nepal side cooperated well to fix the ropes to the summit

- The Icefall Docs did a great job of getting the Icefall in on time

- The helicopter companies bravely rescued over 50 people as high as Camp 2+

- The Nepal Government allowed summit ropes to be flown into the Western Cwm

- The Nepal Government extended 2014 and 2015 climbing permits

- The Hilly Step was not a bottleneck

- Internet worked well at EBC – Nepal!

- The teahouses were not crowded

What Went Wrong

Every coin has two sides so what didn’t go so well:

- 1 Sherpa lost his life

- 5 “members” died on the Nepal side of Everest, many feel all could have been prevented

- Familes read about deaths on the Internet

- The snow was deep on the upper mountain creating slow summit pushes

- Slow teams refused to step aside creating serious problems for faster climbers and subsequent frostbite for some

- The Nepal Government extended 2014 and 2105 climbing permits the day BEFORE the season started

- The ropes never got fixed for Lhotse

- The teahouses were not crowded

Why Climb Everest?

In spite of the relatively safe season, the question of why and debate, sometimes vitriol, swells around the Everest climbing season. I’m always intrigued as to why Everest brings out the , and the worse in people, especially those who make vile comments anonymously over the Internet.

In response to the question of how can you return after two previous years with no summits and how do you pay for it, British climber Mel Southworth, 48, made this amazing post. It is positive yet realistic and not defensive. She owns her ambitions and sacrifices to achieve her goals and doesn’t apologize or ask permission from anyone. This is an excerpt:

There are a million and one ways to live a life. Everyone, including myself, blows money every year on meaningless things. We often forget that money facilitates how we live our lives, but it can’t us happiness or a longer life. I’ve had a family member work hard all his life and die prematurely at the very point he should have been enjoying the spoils of his success. I vowed that the same thing wouldn’t happen to me. I’ve chosen, instead, to spend most of my life traveling for no other reason than the sheer love of doing it, sacrificing having a family and stable home life as a byproduct. Life is short.

If you love Everest, please read it.

If you hate Everest, please read it.

If you know someone who doesn’t understand, please send it.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Alzheimer’s – Why I Cover Everest Each Season

Alzheimer’s – Why I Cover Everest Each Season

I have been reporting on or climbing Everest since 2002. I do this simply to honor my mom, Ida, who died from Alzheimer’s Disease in 2009. My objective is to get you to read about climbing and then to gently add a few words about this deadly disease.

The goal is that you will appreciate my work and make a donation to one of the non-profits I work with to fund a cure, caregiver support and education. All donations go directly to the organizations and never to me. I am not paid by anyone or organization to cover climbing each year on my site. This is truly a labor of love.

• NO CURE, always Fatal

• No easy, inexpensive method of early detection

• 3rd leading cause of death in the US

• New case every 68 seconds, 4 seconds worldwide

• Impacts more than 5+m in US, 25m+ worldwide

• Devastating financial burden on families

• Depression higher for caregivers

• Issues are increasing rapidly as population ages

13 thoughts on “Everest 2016: Season Summary – A Normal Season”

I love it.

Great coverage as always.

To quote you “, but for the third year in a row, Lhotse saw no summits.”.

Why do you think that is? Is Lhotse a significantly more technically difficult mountian to climb? Or is it that there is little money in it for the sherpas and guiding companies ot setup fixed lines on Lhotse? Or some other factors?

Would love to hear your take on this.

Mir.

2014/15 saw no summits on Everest/Lhotse due to serac release/earthquake. This year, I do think Everest took priority and teams were not willing to invest the resources to fix the ropes after the Sherpa died on Lhotse.

Thank you Alan for this years coverage!! I did the Kilimanjaro in 2012 and hope to climb mount Elbrus next year, but the Everest will stay a dream. I started too late as a climber and I now my limits. That is why I follow your blog. Looking forward to read it next year again.

All the best,

Boudewijn van Eersel

Vlissingen, The Netherlands

Elbrus is a fun experience Boudewijn! Dank je

Hi Alan,

Long-time reader, first-time commenter. Suffice to say, I very much enjoy reading your Everest reports! A couple of things…

In your post ‘Why people die on Everest’, you referred to a death this season on the north side “with very unclear details”. Of course, you now report all deaths were on the south side, so is it that this death was erroneously reported by those involved? Or have there perhaps been no further details and it’s unclear whether the death even occurred?

Secondly, is there a publicly-available source that reports all summits of Everest? I’m particularly interested in Ben and Laura Darlington who, as you report, assisted Robert Kay in his descent. I don’t know them, but they hail from my adopted home town of Canberra, Australia. Previous media suggested Ben would attempt a no-oxygen summit, so I’m curious to know whether he achieved this goal.

Cheers,

John.

Thanks John, yes the north death was misreported as on Everest. I was on the same team as Ben and Laura(I was going for Lhotse) but yes they summited both using Os. The Himalayan Database complies all Everest summits but it takes 6-12 months for them to get the final numbers and you need to buy it for about $80.

John, there was a death just reported on the North side that previously went unreported by anyone, including his unnamed guide. Details at http://calgaryherald.com/news/local-news/calgarian-doctor-dies-at-everest-base-camp

Alan, thanks for the quick replies and info. Your factual reporting and lack of ‘spin’ are greatly appreciated.

Tremendous reporting as always Mr Arnette. Very balanced and factual. I salute your motivation to carry on reporting the season despite your own disappointment on Lhotse. I am very pleased you managed to return safely.

Kind regards

Peter

Thank you Peter and for the kind wishes as well.

Thank you Alan, I really appreciate your continued coverage of The Mountain. I am an active 71 years old who dreamed of climbing but never was able. I have lived on the Mountain in many climbing books and in your reporting.

I did resubscribed to the Alzheimers sight this spring, but I am not sure it was credited to you.

My best,

Alice Zacherle

Napa, CA

Thank you so much Alice. Your action and comments are why I do what I do.

Comments are closed.