It’s mid-season, and there are mixed results on the ‘other’ 8000ers and a lot of movement on Everest. The ropes are now at the South Col, and the rope team estimates tagging the summit around May 10, depending on the weather. This is slower than previous estimates. Let’s take a look at acclimatization and climbing the Lhotse Face.

Big Picture

As I previously reported, helicopters were used to ferry the gear needed for the summit fixed line to Camp 2, reducing scores of trips through the Icefall for the Sherpas. Good move by Nepal to be mindful of the Sherpa’s safety. Also, helicopters were used to remove trash from the 21015 earthquake down from Camp 2. Again, kudos, to all involved.

Teams are now scattered all over the Big Hill, working on their acclimatization, from EBC to Camp 3 on the Lhotse Face.

In what seems like a bit of contrived drama, multiple media outlets pasted headlines about missing Italian climber Giampaolo Corona on Annapurna. He was reported lost but then regained radio contact and said he was fine. Unfortunately, this situation is a fairly common occurrence, but happy Giampalo is fine.

See the tracking table for the latest team locations.

The Art of Acclimatizing

acclimatize | əˈklʌɪmətʌɪz | (British also acclimatise) verb [no object] (often acclimatize to or be/become acclimatized to) become accustomed to a new climate or new conditions; adjust: it’s unknown whether people will acclimatize to increasingly warm weather. • technical respond physiologically or behaviourally to a change in conditions in the natural environment. ORIGIN early 19th century: from French acclimater ‘acclimatize’+ -ize.

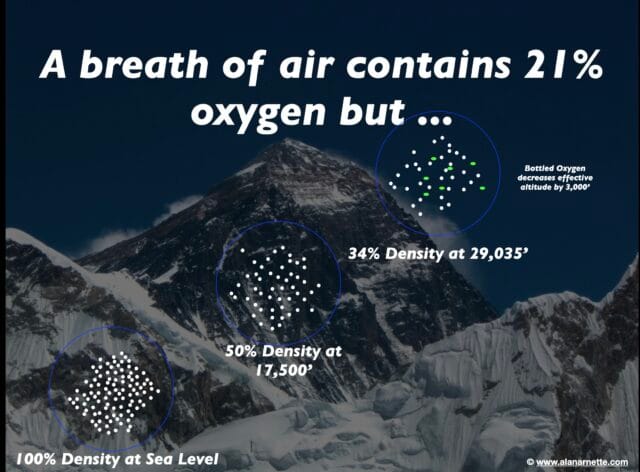

There you have it; acclimatizing is the most critical element of safely summiting Everest. Few humans don’t need to acclimatize. Those who go for an Everest summit without spending a few nights above 6000-meters or higher are destined to return home empty or not return home at all.

It’s pretty easy to tell when you are suffering from altitude. You lack appetite; experience vomiting, headache, distorted vision, and general fatigue. But the trick is that “altitude sickness,” aka AMS symptoms, can vary in severity from person to person, so it’s best to be evaluated by someone who has training in altitude sickness. But in any case, the only true treatment is to descend as quickly and safely as possible.

One of the standard tests to evaluate AMS is The Lake Louise Score, a scoring system of symptoms developed by experts at a conference in Lake Louise, Canada.

The physiological concept of acclimatization is simple, put your body at an altitude with less available oxygen than it had in previous days and the body almost immediately begins to adjust.

Stay there for a while, preferably days, and the body reacts with significant changes in the blood chemistry. Some of the changes include:

- Faster breathing

- Heart rate and blood pressure increase

- less plasma (water) in the blood, so it becomes thicker

- An increased level of hematocrit, the red blood cells that carry oxygen to our muscles

- Increased urination in response to changes in the body’s acid/base balance

- Occasionally, mild swelling in hands, feet, and face

- Frequent awakenings, and light sleep

This is how Everest legend Tom Hornbein, who was instrumental in the development of supplemental oxygen brearthign systems, explained it to the American Lung Association:

The lower oxygen stimulates chemoreceptors that initiate an increase in breathing, resulting in a lowering of the partial pressure of CO2 and hence more alkaline blood pH. The kidneys begin to unload bicarbonate to compensate. Though this adaptation can take many days, up to 80% occurs just in the first 48 to 72 hours. There are many other physiologic changes going on, among them the stimulus of low oxygen to release the hormone, erythropoietin to stimulate more red blood cell production, a physiological and still acceptable form of blood doping that enhances endurance performance at low altitudes. Adaptive changes are not always good for one’s health. Some South American high-altitude residents can have what’s called chronic mountain sickness, resulting from too many red blood cells; their blood can be up to 84-85% red blood cells. The increased blood viscosity and sometimes associated pulmonary hypertension can result in right heart failure.

Studies have shown that red blood cells live for 120 days, but in general, your body will immediately begin to adjust to the current altitude. I’ve used the rule of thumb that you keep your acclimatization for asl long as it took you to get it.

One of the best ways to adapt your body is the time-proven technique of climbing to 7,000-meters on the Lhotse Face, but, oh my, what a struggle. In fact, it is so difficult for many people, they skip this step and start using supplemental oxygen from Camp 2 at 21,500-feet/6200-meters. While I disagree with the early use of Os, for style reasons, that’s my viewpoint only, and it’s becoming more popular each season.

But eventually, if you want to summit Everest, you will need to climb the Lhotse Face, Os or no Os. So what’s it like?

The Lhotse Face

There is no Easter Bunny, no Santa Claus; the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales are dark and scary and magic is real. Today, everyone on Everest believes in magic.

Sitting in your tent at Camp 2, 21,500 feet; you rub the sleep out of your eyes. Your headlamp betrays your cold breath at 3:00 AM. Today you climb the Lhotse Face.

The morning routine is annoyingly familiar. It takes ten times longer than when you were back home to put on your boots. Breakfast is simple – toast, maybe an egg, perhaps hot cereal, and coffee. The Sherpa cooks have been up since 1:00 AM heating water so you eat with gratitude. But really all you want to do is crawl back into your warm sleeping bag.

Sitting silently in the dining tent, your curse the tiny golf chairs for their instability, but then you consider where you are and are glad to have anything to sit on. Taking the last sip of coffee, you turn on your headlamp.

Stepping out of the tent, you kneel down to put on your crampons but then look up. The moon is lighting up the ‘Face’ it looks huge. Squinting you look for Camp 3, maybe you see it, probably not. Finishing your crampon work, you take another deep breath.

The walk to the base of the Lhotse Face is familiar, you did this a few days ago to get some exercise. But that was in the daylight, now in the dark; it seems to go on forever. You don’t remember the elevation gain and find yourself breathing hard once again. The morning blues…

Approaching the base you glance at your watch, which took an hour. Once again you look up. Now all you see is snow and ice. Bending over you clip your carabiner and jumar onto the white nylon rope – that is your lifeline. With ice axe in the other hand, you begin.

The first section seems steep but you have read all about the Lhotse Face so this is not a surprise. But it is steep, seriously steep; not quite what you were expecting. OK, it should ease shortly – you try to convince yourself. At least that is how it looked from Camp 3.

Now two hours in, your mind wanders. You hear the voices of those back home when you told them you were going to Everest. The negative surfaces: “why, are you crazy, glory er, rich spoiled brat, peak bagger, selfish, …”

The naysayers were loud, but not to your face. You heard them, you know what some people say about those who climb Everest. You fight to keep the voices from growing into doubts. You know why you are here, who believes in you, your belief in yourself.

Glancing up from your feet, you now see the Lhotse Face up close. The ice is hard, translucent, and blue. You stare at your crampon front points. “Damn, I wish they were sharper”, you mumble out loud. The wind picks up blowing a bit of snow in your face. Actually, you don’t mind, it takes you away from the dark thoughts.

Looking around you see a few of your teammates. The Sherpas seem like they are everywhere. You are on the up rope. There is another rope to your left, the down rope. They seem to go on forever. You are careful not to put your weight on the rope, that is not the purpose. They are there to stop a fall, not to get you up the hill, but you cheat.

Once again, the voices are loud. But real this time. You step to your right to let a few faster climbers go by. Once again, a high-altitude ballet.

You are attached to the line by two thin strips of nylon, webbing. They are attached to a carabiner and a jumar. The jumar has small teeth going in one direction that will catch you if you fall in the opposite direction. A golden rule is to always stay attached to the rope.

You make eye contact with the other climber. No words are spoken, perhaps a nod is exchanged. She unclips her ‘biner while keeping the jumar attached. She reaches around you to clip the ‘biner back onto the rope ahead of you. You stand still not wanting to make any movement that might throw both of you off balance.

You make eye contact with the other climber. No words are spoken, perhaps a nod is exchanged. She unclips her ‘biner while keeping the jumar attached. She reaches around you to clip the ‘biner back onto the rope ahead of you. You stand still not wanting to make any movement that might throw both of you off balance.

She takes a few small steps around you and reaches back to unclip the jumar. Successfully past you, the slow obstacle, she reattaches the jumar and climbs higher. You stand, staring, not sure to be impressed or depressed.

Once again focused on your own climb, you see the trail ahead, steps kicked into the hard face. You are grateful now for the traffic on the Lhotse Face. There are small buckets in the ice to plant your feet. Somehow the steps provide a placebo that it will be easy to reach Camp 3, 23,500 feet. The steps are few and far between, loose and soft, unreliable today, maybe they will be different next time up. You are on a steep, slick mountainside that requires constant concentration.

More steps, more clips. The fixed rope is attached to the earth every few hundred feet. Each anchor requires a series of actions. You are glad you spent the extra money on the good gloves.

Your down jacket has felt good but now with the sun rising over the summit of Lhotse, you begin to think about layers. Great, now you are getting a bit warm. OK, it feels good but not too much warmth. You are never satisfied, are you?

As usual, the tents ahead appear out of nowhere. The climb thus far has been a series of steep sections followed by a short flat spot – a cruel trick. You took your breaks, ate, drank, you are actually doing well. But the tents are a welcome sight.

Wait, there are three Camp 3s! Another cruel trick. The Face is too steep to put all the tents needed in one spot. Yours is the highest. This irony is good news, bad news. Today you suffer, but on the summit push, you will have an advantage.

Passing other tents, you see fellow climbers in their tents. You smile at them and curse under your breath. Jealously fuels your steps higher. Actually, no one is watching you but your vanity runs wild. You stiffen your back, You focus on your form. Step, plant the ice axe, step, move the ‘biner, step, move the jumar, stand up straight, look ahead, smile for the camera!

Passing the last of the tents, you now only see a high bump in the ice. If you were home, where you trained, you would pass this is a matter of minutes, maybe seconds. But at 23,600 feet, you stop and stare once again. Breathing heavily, you muster whatever is left and take a few more steps. Higher, slower; the climb is taking a toll on your body. You no longer look anywhere but at your feet interrupted by a short glance at the next anchor. Your style is zombiesque.

A familiar voice calls out your name. A Sherpa from your team. He waves you with enthusiasm towards the yellow tent. Stepping carefully through a maze of lines, you slowly move towards him. You have no choice but to move slowly. You are nakered.

Finally reaching your tent. You collapse in a down-covered heap. The poor goose who made the donation would not be proud. Careful with your crampons, you finally swing around to see where you are. Your breathing continues to be heavy. You have the hundred-yard stare. A bit of water helps begin the recovery. Your head bobs.

Slowly you come around. Your mind thinks like you are texting with a simple OMG. It is justified. The scene before you defies words. OMG. Slowly your eyes trace the perimeter: Nuptse to your left, The Western Cwm front and center, Everest to the right.

Are you really there? Again you scan the view. Now you see Pumori. it looks tiny. It dominates your view at Base Camp. What happened – you are more than a mile higher, that’s what happened.

On the horizon, you spot Cho Oyu, the world’s 6th highest peak. You recognize the flat summit plateau. Maybe that will be next. You are thinking clearly now, or not.

More water. Your breathing is slow. Your heart is steady. You are in control.

Sitting there on the snow-covered Lhotse Face, it sinks in that you are climbing Everest, well Lhotse technically. But you glance over your right shoulder and see the massive shoulder of the world’s highest mountain.

This cannot be real. It must be magic.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Nepal Permit Update as of April 29, 2022

The permits for Everest are leveling out albeit around 100 less than the record set in 2021 of 408. Climbing permits have been issued for 889 climbers from 74 countries for 25 peaks. Looking at Everest only, the US has the largest representation with 64 members, followed by the UK-34, Nepal (non-Sherpas)-21, India-23, Canada-17, Russia-17, France-13, China-14, and Austria with 11. There are 37 countries represented by one or two climbers.

These permits have generated $3.8M in royalties for the government. Almost all of this revenue stays in Kathmandu, with some in various personal pockets and none to the Sherpas, porters, or other high-altitude workers. The Nepal Ministry of Tourism posted these foreign permit tally as of April 29, 2022:

- Everest: 316 on 39 teams (an unusual amount of very small teams this year)

- Ama Dablam: 97 on 9 teams

- Annapurna I: 26 on 4 teams

- Annapurna 4: 9 on 1 team

- Baruntse: 20 on 3 teams

- Bhemdang: 8 on 1 team

- Dhaulagiri: 27 on 3 teams

- Gangapurna: 2 on 1 team

- Himlung: 35 on 4 teams

- Khangchung: 68 on 7 teams (many very small teams this tear)

- Kangchung/UIAA: 2 on 1 teams

- Lhotse: 112 on 12 teams

- Makalu: 39 on 4 teams

- Manaslu: 9 on 1 team

- Mukot: 4 on 1 team

- Norbu Khang: 5 on 1 team

- Nuptse: 57 on 7 teams

- Phu Khang: 5 on 1 team

- Pokhar Kang: 9 on 1 team

- Putha Hiunchuli: 14 on 1 team

- Ratna Chuli: 9 on 1 team

- Saribung: 10 on 2 teams

- Saula: 2 on 1 team

- Thapa (Dhampus): 12 on 4 teams

- Urknmang: 2 on 1 team

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2022 podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

Summit Coach

If you dream of climbing mountains but are not sure how to start or reach your next level from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers throughout the world achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 25 years of high altitude mountain experience, including summits of Everest, K2, and Manaslu, and 30 years as a business executive.