Welcome to the kick-off for my Everest 2026 coverage! 2026 marks my 23rd year covering all things Everest. If you’re a long-time reader, welcome back. If you’re new here, thanks for joining me.

I summited Everest on May 21, 2011, and have climbed on the mountain three other times, all on the Nepal side, in 2002, 2003, and 2008. In these attempts, my high point was just below the Balcony around 27,500 feet (8400 meters) before health, weather, or my judgment forced me to turn back. I also attempted Lhotse in 2015 and 2016.

When not climbing, I cover the Everest season from my home in Colorado as I did in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, and now the 2026 season. In 2020, when both sides of the mountain were closed due to COVID, I ran a virtual series, Virtual Everest 2020 – Support the Climbing Sherpas, to raise money for the out-of-work Sherpa community working with nine commercial guiding companies.

Although the climbing season is still a few months away, I’ll be publishing several big-picture articles before activity ramps up in early April, including:

- Welcome to Everest 2026 Coverage – An overview of what to expect during the Spring 2026 climbing season

- Everest by the Numbers: 2026 Edition – A deep dive into Everest statistics as compiled by the Himalayan Database

- Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2026 Edition – A detailed look at Everest’s routes, commercial, standard, and non-standard

- How Much Does it Cost to Climb Everest: 2026 Edition – My annual analysis of Everest climbing costs, from solo and unsupported to fully guided

Once the season begins in early April, updates become more frequent and more intense during the summit pushes in mid-to-late May. You can sign up for (or cancel) email notifications in the lower-right sidebar, or simply check the site regularly.

Why This Coverage?

I have one reason for this coverage: Alzheimer’s. I lost my mother, Ida, and four aunts to the disease. Like many families, mine was changed forever, and I don’t want anyone else to go through this journey.

If this coverage has value to you, I hope you’ll consider supporting Alzheimer’s research or caregivers through the organizations listed on my website—or any organization you choose. I receive no financial benefit from donations. Thank you for reading, and for considering a donation. Click the button to donate.

How I Cover Everest

My goal has always been to provide clear insight and thoughtful analysis—without favorites, sponsors, or hidden agendas. I draw on firsthand accounts from the mountain, public data, and my own experience to tell each season’s story as accurately as possible. I rely heavily on data from the Himalayan Database (HDB) for summit and death statistics. The HDB—free to download—documents climbs on Nepalese and Tibetan peaks (excluding Pakistan), dating back to 1905.

Definitions

Before we get going, let’s define a few terms. I use the HDB terms for climbers and guides, for example, “hired” refers to support staff, including Sherpas and other ethnic groups such as Tamang, Magar, and Rai; on the north side, Chinese and Tibetan workers fill similar roles. “Member” typically describes a climber paying for guided support. I use “members,” “foreigners,” and “Westerners” interchangeably, though some climbers—such as those from South Korea—do not consider themselves Western. Refinements to these definitions are welcome:

- Acclimatization: A process of repeated climbs to progressively higher camps, with returns to lower elevations to sleep, allowing the body to adapt to reduced oxygen availability. More information.

- Alpine Style: A single, continuous ascent without supplemental oxygen, Sherpa or team support, fixed ropes, or pre-established camps. The climber carries all equipment and supplies, makes no acclimatization rotations, and leaves no trace beyond footprints. Climbs may be solo or in very small teams. Alpine-style ascents of Everest are now extremely rare.

- Attempt: A climber leaving base camp with the intent to reach the summit.

- China/Tibet side: China’s jurisdiction of Everest’s north side, commonly known as the Northeast Ridge or North Col. I typically use “Tibet” when referring to the north side.

- “Conquering the Mountain”: A misconception. Mountains are climbed and descended; they are not conquered.

- Expedition (Siege) Style: A staged ascent involving multiple acclimatization rotations to progressively higher camps. Fixed ropes and ladders are used on technical sections, and camps are often stocked in advance, sometimes by hired personnel. Nearly all modern Everest ascents use an expedition-style approach.

- Hired/Guides: Individuals paid to support or guide Everest climbs, including Sherpas, Tibetans, Western guides, and other hired personnel. More information.

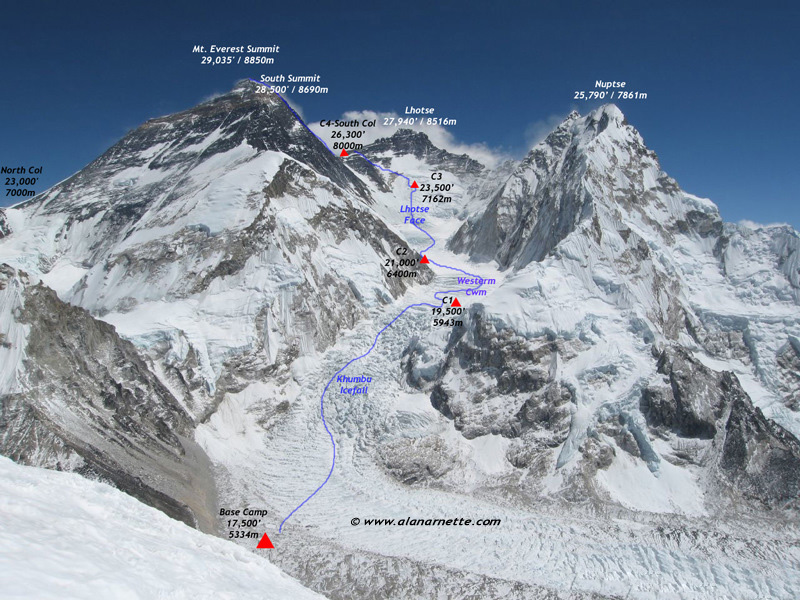

- Icefall Doctors: A team of approximately ten Sherpas responsible for installing and maintaining the fixed route between Base Camp and Camp 2 on the Nepal side. Managed by the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) and funded through permit fees. The term was coined in the early 1990s by Rob Hall and Gary Ball of Adventure Consultants.

- Independent Climber: Anyone who is part of a team but climbs alone without a Sherpa or Tibetan support. They use infrastructure such as ladders and ropes, along with the team’s logistics, to move from base camp to high camps.

- International Operators—Guide companies based outside Nepal (e.g., the U.S., Europe, Asia, Australia, etc.) that run Everest expeditions but, by regulation, partner with Nepal- or Tibet-based logistics teams for permits and to meet government rules.

- Leave No Trace: A commitment to remove all human-made materials from the mountain, including waste, oxygen bottles, ropes, tents, and debris. Nothing is left behind. More information.

- Members: Individuals who pay to be part of an expedition, including those who use only base camp services and climb independently above base camp. More information.

- Nepal side: Nepal’s jurisdiction of Everest’s south side, commonly referred to as the Southeast Ridge or South Col route.

- No O’s: Climbers who do not use supplemental oxygen at any point, including while sleeping or during descent. Fewer than 3% of all Everest summiteers have climbed without oxygen. Of the 327 recorded Everest deaths since 1924, 178 (54%) occurred without supplemental oxygen.

- Pre-Acclimatization: A technique in which climbers sleep at home in altitude tents connected to oxygen-reducing generators prior to arriving on the mountain. Commonly used on expeditions lasting less than three weeks (“rapid” or “flash” climbs). Some studies suggest acclimatization equivalent to elevations up to 7,000 meters. More information.

- Rotation: A staged climb used in expedition style to establish higher camps and promote acclimatization, with repeated ascents and descents between camps. Modern Everest teams typically complete two to five rotations, sometimes supplemented by climbs of nearby peaks, before arriving at base camp.

- Solo Climber: A climber who ascends entirely alone without teammates, Sherpa or Tibetan support, fixed ropes, ladders, or shared logistics. The climber carries all equipment, establishes all camps, and prepares all meals above base camp. More information.

- Summit: When a climber reaches the summit, regardless of outcome on descent , without external transport assistance, e.g., aviation, animal, or carried.

- Team Member Summit Success Rate: the number of members who summit divided by the total number of members who initially arrived at base camp.

- Western: Any climber, guide, or company based outside Nepal or Tibet.

2025 Review

Strong winds, drones, demanding climbing, and increasingly sophisticated logistics defined the 2025 Everest spring season. Frostbite cases and helicopter evacuations were common, though many incidents likely went unreported. Once again, Everest reminded climbers that at 8,848 meters, preparation is non-negotiable.

According to the Himalayan Database’s December 2025 update, 851 climbers reached the summit during the spring season — 731 from Nepal and 120 from Tibet — making 2025 the third-busiest Everest season on record, behind only 2019.

On the South side, 303 members were supported by 428 Sherpas, a 1.4:1 support ratio that reflects the growing need for assistance among less experienced climbers. The North side saw 68 members and 52 Sherpas, a 0.76:1 ratio, consistent with its appeal to more seasoned alpinists.

Men accounted for 766 summits (56% success rate), while 85 women reached the top with a notably higher 76% success rate, continuing a strong upward trend in women’s participation and performance. Nearly every climber used supplemental oxygen — all but four — highlighting its central role in modern Everest support.

Route Performance

Some of the best mountaineering guides had stellar days, proving that Everest can be climbed without crowds or drama. On the South side, 63% of members with permits (303 of 481) summited. Madison Mountaineering summarized their summit experience:

“Our Mount Everest team just returned to Kathmandu after a successful summit on May 23rd. They enjoyed a perfect summit day with no crowds—a rare gift on the world’s highest peak—and had the top of the world entirely to themselves!”

The North side posted a much higher rate of 86% (68 of 79). Alpenglow noted:

“This spring, our Alpenglow Expeditions team returned to the North Side of Mount Everest with a small crew and a big plan. After months of preparation, pre-acclimatization, and weather watching, our Everest expedition 2025 culminated in an incredibly rare summit day—blue skies, no wind, and a quiet mountain.”

Losses and Lessons

Tragically, five climbers died last season, all on the Nepal side, resulting in a fatality rate of approximately 0.6% of summits, among the lowest on record, reflecting improvements in logistics, weather forecasting, and guided expeditions. Still, each number represents a human life and a reminder of Everest’s narrow margin for error.

Rescues

Global Rescue, a widely respected evacuation provider, reported a dramatic increase in rescues during April and May 2025, again pointing to a growing number of inexperienced members or underprepared operators.

“We handle several rescue operations every day throughout the spring Everest climbing season, keeping our team engaged from before sunrise well into the night,” said Dan Stretch, a Global Rescue operations manager who has overseen more than 500 evacuations and crisis responses in the Himalayas. “At peak activity, our medical and rescue teams have performed up to 25 rescues in a single day, sometimes more.”

Summit Records

Several achievements stood out:

- Kami Rita Sherpa (55) completed an unmatched 32nd Everest summit.

- Kenton Cool (51) extended his non-Sherpa record with a 19th ascent.

- Anja Blacha (34) became the first German woman to summit without supplemental oxygen, doing so on the season’s final summit day.

- Saad bin Munawar became the first Pakistani climber to summit from the North Side in May.

What the Season Taught Us

The season reinforced several long-running trends:

Shorter expeditions:

Average time from arrival at base camp to summit dropped to 28 days, down from 33 in 2019 and 48 in 2000. Pre-acclimatization — both on nearby peaks and at home using hypoxic tents — is now more popular than ever.Higher support ratios:

On the South side, 1.5 Sherpas per member has become the norm, with some teams operating at 2:1 or higher, especially when using supplemental oxygen, which requires a second Sherpa to carry the extra oxygen.Standardized operations:

Everest has become a formula climb, with fixed routes, consistent camp locations, and centralized rope management by Nepal’s expedition operators.Rising comfort:

Internet access, heated tents, real beds, and multi-course meals are now common, despite regulatory attempts to curb excess.Weather remains decisive:

Jet stream variability, unstable windows, and congestion at traditional bottlenecks continue to define success or failure more than fitness or guiding.

Everest in Context

Viewed historically, Everest has become markedly safer despite increased traffic. Between 1923 and 1999, there were 1,170 summits and 170 deaths, a fatality rate of 14.5%. From 2000 to 2025, climbers achieved 12,567 summits with 169 deaths, reducing the fatality rate to approximately 1.3%.

Several years stand out for elevated death tolls: 1996, 2014, 2015, 2019, and 2023, largely due to natural disasters such as serac collapses, earthquakes, and avalanches.

On the Nepal side, approximately 33% of member fatalities (75 climbers) occurred during the descent, when exhaustion overtakes climbers’ strength, while 23 died during ascent. On the Tibetan side, 51 climbers (46%) died on descent and 12 during ascent. Remaining deaths occurred during route preparation or at base camp.

Across the world’s highest mountains, death rates continue to decline due to higher support ratios, reliable oxygen systems operating at flows up to 8 liters per minute, improved climbing gear, accurate forecasting, and professional guiding on standardized routes. While Everest has the highest absolute number of deaths (339), its death rate is relatively low at approximately 1.07% among the fourteen 8000-meter mountains.

By comparison:

- Annapurna I has recorded roughly 75 deaths against 510 summits, a fatality rate near 15%.

- K2 has reduced its fatality rate from about 25% historically to roughly 12% today, largely due to commercialization and strong Sherpa-led logistics.

- Cho Oyu remains the safest 8,000-meter peak at 0.53%, followed by Lhotse at 0.62%.

As for the 2025 summits, the Himalayan Database reported in December 2025, based on numbers reported by the Nepal government:

Summits and Deaths for 2025

| NEPAL | TIBET | TOTAL | |

| Members | 303 | 68 | 371 |

| Hired | 428 | 52 | 480 |

| TOTAL Summits | 731 | 120 | 851 |

| % of Total | 91% | 9% | |

| Summit Rate | 68% | 67% | 68% |

| Member Deaths | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Hired Deaths | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| TOTAL Deaths | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| % of Total | 100% | 0% | |

| Death Ratio | ~1% | 0 | ~1% |

Safety on Everest continues to correlate strongly with experience, support, and cost. In 2023 and 2024, 23 of 26 fatalities occurred on expeditions priced below the median, reinforcing a hard truth: on Everest, cutting costs often means cutting margins for error. Continue reading about Everest 2024.

2026 Preview

For spring 2026, I expect 900 to 1,000 total summits from both sides combined, exceeding the previous high-water mark set in 2019, when 877 climbers summited (661 from Nepal, 216 from Tibet. A realistic breakdown for 2026 would include at least 225 summits on the Tibet side (members and hired combined) and well over 800 from Nepal, compared to 731 from Nepal and 120 from Tibet in 2025.

Nepal

Operationally, expect continued drone use, particularly in the Khumbu Icefall, to support the Icefall Doctors by ferrying ropes, ladders, and equipment across the Icefall, reducing the number of heavy-load carries and lowering Sherpas’ exposure to falling or collapsing ice structures. Drones are also expected to play a larger role in removing waste from high camps, helping clean the mountain without adding to Sherpa workloads.

Over the past year, Nepal has announced multiple new rules in the Tourism Bill 2081 that have not yet been approved. You can follow its current status at this link, which is listed as “Discussion in Committee” as of January 2026.

Among the new rules from Nepal is a proposal to eliminate the $4,000 refundable trash deposit per expedition and replace it with a nonrefundable $4,000 fee per climber to fund a Sherpa-staffed checkpoint at Camp 2 that will monitor that climbers bring down what they’ve brought up. It’s unclear how operators will manage this new fee when or if it goes into effect, i.e., absorb it or pass all or part of it on to members.

Nepal’s decision, implemented in September 2025 to raise the Everest climbing permit for foreign climbers from $11,000 to $15,000, is unlikely to significantly reduce overall demand. Price competition among lower-cost Nepalese operators remains intense, while demand for premium, fully guided expeditions led by foreign operators continues to grow. However, the higher permit fee may push a modest number of climbers toward the Tibetan side, particularly those seeking fewer crowds and a more controlled climbing environment. Note that this permit increase is in addition to the proposed $4,000 trash fee.

So, where does the extra $4,000 in the permit fee go? Nepal insists it will be reinvested in maintaining a clean and orderly mountain, but has an uneven track record of implementing and enforcing any new rule.

Rescue and Safety Infrastructure: A portion of the fees will fund upgraded on-mountain medical facilities and a more robust rescue response system. The goal is to reduce response times for high-altitude emergencies, which reached a breaking point during the heavy 2023 and 2025 seasons.

Environmental Conservation: Revenue is directed to the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) and other waste management initiatives. This includes funding the removal of decades-old trash and abandoned gear from the higher camps (Camp 3 and Camp 4).

Local Community Development: By law, a percentage of permit royalties must be distributed to the local district. These funds are used for schools, clinics, and infrastructure (such as bridges and trails) in the Khumbu region, ensuring that the communities that support Everest receive direct benefits.

Staff Wages: New regulations have increased the minimum daily pay floors for Sherpas, Sirdars, and Liaison Offices. The permit hike helps subsidize the increased administrative and insurance costs associated with these higher labor standards.

Beyond the previously mentioned changes, there is widespread confusion about a set of new rules proposed by the Nepal Ministry of Tourism, as I described in a post last year. The most significant change is that all Everest permit applicants must have climbed a 7000-meter peak in Nepal. Note that Aconcagua or Denali would not qualify you to climb Everest.

Tibet

China has returned to normal operations after a few years disrupted by the pandemic. From 2019 to 2022, only Chinese scientists and technicians were allowed to climb, and they installed and maintained a weather station near the summit.

Unlike Nepal, which has no limit on the number of permits issued for Everest, China has a maximum of 300 annual permits for hired and member teams. The only time there were more summits than 300 was in 2007, when 197 members, supported by 178 hired, reached the top, totaling 375. Since 2010, the median has been well under the quota of 153 people, so this should not be an issue in 2026. However, we may see the North side crowds increase in 2026 as Nepal’s price increase for the Everest takes effect.

Only a few Western companies, including Alpenglow Expeditions, Furtenbach Adventures, Kobler & Partner, and Summit Climb, regularly, but not always, guide on the Tibetan side. Most established Nepalese and Tibetan operators run expeditions, such as Lhasa-based Yala Xiangbo Mountaineering Adventure Co., Climbalaya, and Seven Summits Treks.

There are a few new rules for this season, but, as usual, China does not publish them publicly; it announces them only to selected operators. For example, last year they announced that all climbers must use supplemental oxygen on all three of their 8000-meter peaks, but not every operator received that guidance. Also, they announced that for 2026, all Everest climbers must have climbed a 7,000-meter peak. It’s unclear whether any of these requirements are enforced; for example, last year several climbers summited 8000ers in Tibet without supplemental oxygen.

Follow the 2026 Everest Coverage!

Everest Guides

A significant shift in the guiding industry began around 2013. That was when Nepalese expedition operators began marketing Everest expeditions and the other 8000ers at low prices, using well-designed websites. Unlike foreign guides, Nepalese companies do not have to pay permit fees for Nepalese guides and traditionally pay lower wages. These savings are passed on to their clients through lower prices.

This business model attracted a new demographic of price-conscious climbers, mainly from China, India and Southeast Asia. One of their marketing promises was, “No experience required; we’ll teach you everything you need to know on the mountain.” This business model has been very successful, albeit with an increase in proportional deaths andrescues.

Who guides on Everest continues to consolidate. Longtime companies still run annual expeditions. These include Nepalese operators such as Asian Trekking and Western guides Alpine Ascents International, Summit Climb, International Mountain Guides, and Himex (now sold and inactive on Everest). These outfits created the Everest climbing industry. They are now joined by relatively recent newcomers (the last 10 years), such as Climbing the Seven Summits, Furtenbach Adventures, Madison Mountaineering, and Mountain Professionals. These companies’ prices range from $57,995 (Climbing the Seven Summits’ Sherpa-Supported Climb) to $230,000 (Furtenbach Adventures–Signature Expedition).

The most prominent Nepalese-owned operators may have over 100 members, compared with 20 or fewer on Western guiding trips. These Nepalese outfits include 8K Expeditions, 14 Peaks Expeditions, Asian Trekking, Elite Expeditions, Imagine Nepal, Pioneer, and Seven Summits Treks. Smaller Nepalese companies include Arun Treks, Ascent Himalaya, Climbalaya, Satori Adventures, and Thamserku. Today, there are around 2,000 “trekking” agencies registered in Nepal. Most Nepalese guides charge between $30,000 and $50,000 for either side of Everest.

The best operators use professional guides who are UIAGM/AMGA/IFMGA-certified. They charge more for this expertise, but it can be a life-or-death difference if you encounter an emergency, such as an injury or altitude issues. Remember that not everyone called a “guide” is a qualified guide. Each company can call its staff whatever it likes.

2026 Demographics = Crowds

Given the dynamics discussed, I expect another year of crowds on Everest. Crowding is a disturbing trend that began several years ago. Low prices continue to attract climbers with little experience, as shown by the nightmare line of people between the South Summit and the Summit in 2019. Members struggled with altitude and moved too slowly, and the guides failed to manage the clients, allowing the line to clog the system. This scenario was like following a frustratingly slow driver on a one-way mountain road with steep drop-offs on both sides, with no way to pass.

The best guides will use professional weather forecasts to select a suitable weather window of several days when summit winds are under 30 mph. They will let the rush that always occurs just after the ropes are fixed to the summit subside before going for their summit push. The best companies have used this strategy for years, achieving excellent summit success and safety.

Bugs to a Light

Everest has an immutable attraction that is oddly perverse. When there is a record number of deaths, the following season has more climbers than the previous deadly one. For example:

- 2006: 11 deaths, 494 summits

- 2007: 7 deaths, 634 summits

- 2012: 10 deaths, 581 summits

- 2013: 8 deaths, 684 summits

- 2014*: 16 deaths, 134 summits

- 2016: 5 deaths, 679 summits

- 2023: 18 deaths, 668 summits

- 2024: 8 Deaths, 787 summits

- 2025: 5 Deaths, 851 summits

* The 2014 season ended early when 16 Sherpas died in the Icefall. 2015 closed because of the earthquake.

The pattern is clear: higher death years rarely deter future demand. We’ll see what 2026 brings, but history suggests it will be a big year, especially with the North open and potential changes to Nepal’s eligibility requirements encouraging climbers to climb now to avoid them.

Risks and Wildcards for 2026

Despite strong indicators pointing toward a record-setting season, several variables could meaningfully alter outcomes in 2026:

Weather volatility remains the single largest wildcard.

Jet stream instability over the Himalaya continues to produce shorter, less predictable summit windows. A single stalled weather system in mid-to-late May could compress summit attempts into fewer days, like in 2019, sharply increasing congestion or cutting the season short, regardless of preparation.

Nepal–China border policy and access to Tibet.

The Tibetan side remains sensitive to political and regulatory shifts. Changes in Chinese border policy, permit availability, or expedition caps could quickly reduce North side access — or, conversely, open the door to increased traffic if restrictions ease.

Khumbu Icefall stability.

While drones and reduced loads may lower Sherpa risks, the Icefall itself remains inherently unstable. A major serac collapse early in the season could delay route fixing, restrict traffic, or temporarily close the South side.

Operator quality divergence.

The growing gap between well-capitalized, professional operators and low-cost providers remains a risk. Substandard logistics, oxygen mismanagement, or inexperienced guiding could lead to localized incidents that ripple across the season.

Rescue capacity saturation.

With higher climber numbers and shorter summit windows, helicopter and high-altitude medical resources could be stretched thin during peak periods, especially if weather limits flight days.

Geopolitical and regulatory surprises.

Sudden policy changes — whether related to aviation, drones, insurance, visas, or expedition oversight — could quickly reshape the season with little notice.

Bottom line:

Demand, technology, and logistics continue to push Everest toward higher summit totals, but weather, access, and systemic capacity limits remain the ultimate governors. In 2026, the margin between a record season and a disrupted one will again be narrow.

Here’s to a safe season for everyone on the Big Hill.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Follow the 2026 Everest Coverage!

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2026 podcasts on Spotify, Apple, Breaker, Pocket Casts, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

Preparing for Everest is more than Training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are unsure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers worldwide achieve their goals through a personalized approach based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountaineering experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

Everest Pictures and Video

© All content and images owned and copyrighted by Alan Arnette unless noted. Unauthorized use and reproduction are strictly prohibited without specific permission.

A tour of Everest Base Camp by Alan Arnette

Alan Arnette became the oldest American to summit K2 in 2014. He has also made six expeditions to Everest or Lhotse, including a summit of Everest in 2011. He climbs to raise money and awareness of Alzheimer’s disease.

9 thoughts on “Everest 2026: Welcome to Everest 2026 Coverage”

Thanks Alan: YOU are the Best . ! & you truly are so appreciated!!!!

For Alan

Hi, just my opinion but also from personal experience, being a faithful reader of your blog, I wondered if you might add some definitions for the Ice Fall Doctors (you mention them, but a new reader of your blog might think they are actually medical doctors), 8000\’ers, fixed ropes, and maybe some of the equipment used by climbers.

Looking forward to your commentary on the 2026 season!

Best,

Claudia Groenevelt Atlanta, GA

THnaks for the suggestion, Claudia. I added “Icefall doctors: The team of around ten Sherpas dedicated to installing the fixed rope between Base Camp and Camp 2 on the Nepal side. The Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) manages them, and they are paid through permit fees. In the early 1990s, Adventure Consultants’ Rob Hall and Gary Ball coined the term while comparing their work to that of a surgeon.”

I be look forward to you updating reports Alan

Thanks Jacqueline! Noce to see you again.

Excited for 2026 coverage

Thanks Erika!

Hi Alan… Ginny Lyford from Sunriver, Oregon back again. Always appreciate and look forward to your Everest posts…. You are an amazing source of information every year… My ONLY source!

Appreciate you, Ginny.