Welcome to my ongoing Everest 2026 coverage! 2026 marks my 23rd year covering all things Everest. If you’re a long-time reader, welcome back. If you’re new here, thanks for joining me. Everest by the Numbers: 2026 Edition is an exhaustive review of data and statistics related to Everest mountaineering.

I rely heavily on data from the Himalayan Database (HDB) for summit and death statistics. The HDB—free to download—documents climbs on Nepalese and Tibetan peaks (excluding Pakistan), dating back to 1905.

I use their terms for climbers and guides. For example, “hired” refers to support staff, including Sherpas and other ethnic groups such as Tamang, Magar, and Rai; on the north side, Chinese and Tibetan workers fill similar roles. “Member” typically refers to a climber who pays for guided support. I use “members,” “foreigners,” and “Westerners” interchangeably, though some climbers—such as those from South Korea—do not consider themselves Western. I define an attempt as a climber leaving base camp with the intention to summit.

This post is a complementary post to the following articles as we near the start of the season in April.

- Welcome to Everest 2026 Coverage – An overview of what to expect during the Spring 2026 climbing season

- Everest by the Numbers: 2026 Edition – A deep dive into Everest statistics as compiled by the Himalayan Database

- Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2026 Edition – A detailed look at Everest’s routes, commercial, standard, and non-standard

- How Much Does it Cost to Climb Everest: 2026 Edition – My annual analysis of Everest climbing costs, from solo and unsupported to fully guided

You can sign up for (or cancel) email notifications in the lower-right sidebar, or simply check the site regularly.

Why This Coverage?

I have one reason for this coverage: Alzheimer’s. I lost my mother, Ida, and four aunts to the disease. Like many families, mine was changed forever.

Everest is where I focus my work, but Alzheimer’s is why I do it. If this coverage has value to you, I hope you’ll consider supporting Alzheimer’s research or care through the organizations listed—or any organization you choose. I receive no financial benefit from donations. Thank you for reading, and for considering a donation. Click the button to donate.

Overall Numbers (Through December 2025)

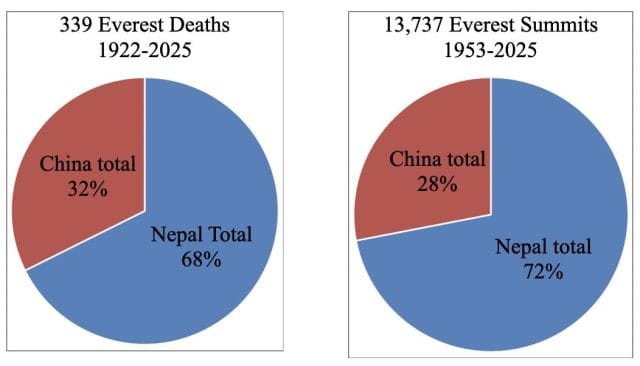

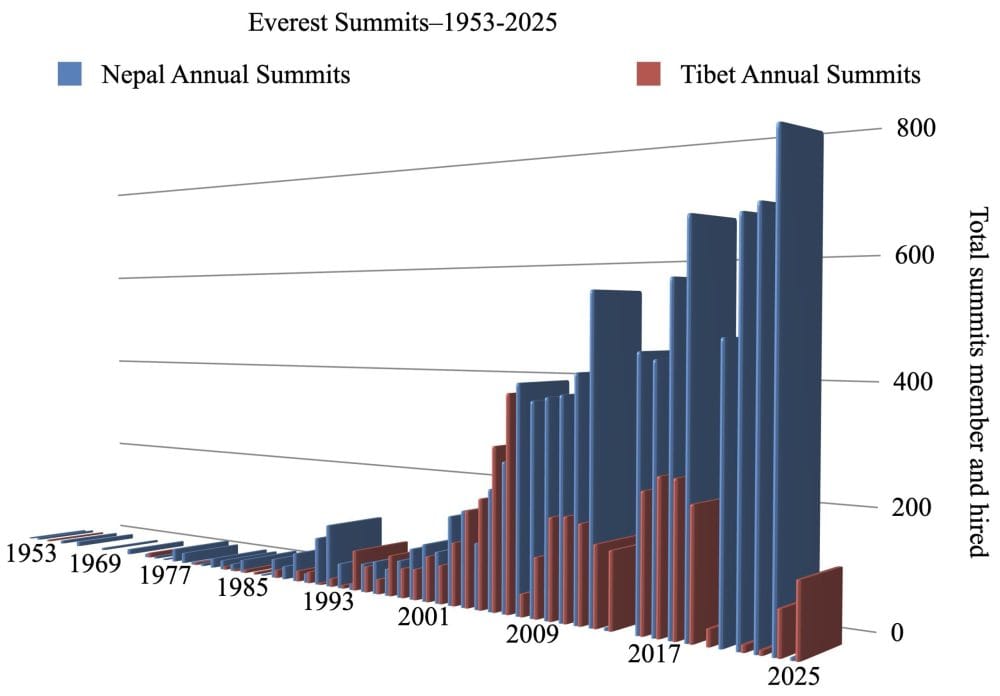

Looking at the overall numbers, there have been 13,737 summits of Everest, representing a 43% summit success rate, (summits divided by attempts above base camp) through December 2025, on all routes, by 6,656 members (clients) and 7,081 hired climbers (Sherpas). Of those who have summited, 7,563 different people have reached the top. As for deaths on all routes, 339 people have died. Nepal remains the more popular—and more deadly—side. Hired support climbers now dominate with the most summits.

Repeat ascents account for a significant share of that total, including 1,179 members and 1,284 Sherpas, together responsible for 7,083 summits. Women members have recorded 1,047 summits, a figure that continues to grow steadily.

Summits and Deaths from 1922 to 2025

| NEPAL | TIBET | TOTAL | ||

| Members | 4,547 | 2,109 | 6,656 | 48% |

| Hired | 5,340 | 1,741 | 7,081 | 52% |

| TOTAL Summits | 9,887 | 3,850 | 13,737 | |

| 69% | 31% | |||

| Member Deaths | 122 | 86 | 208 | 61% |

| Hired Deaths | 107 | 24 | 130 | 39% |

| TOTAL Deaths | 229 | 110 | 339 | |

| 68% | 32% | |||

| Death Rate | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.06 |

Follow the 2026 Everest Coverage!

Tibet or Nepal Side?

The Nepal (South) Side remains the most popular route and has recorded the highest absolute number of fatalities: 9,887 summits and 229 deaths, a fatality rate of approximately 2.3% (or 1.07 deaths per 100 summits, depending on methodology). The Tibet (North) Side has seen 3,850 summits and 110 deaths, a slightly higher fatality percentage of 2.8%, but a comparable normalized rate of 1.05.

Use of supplemental oxygen remains one of the strongest predictors of survival. On the Nepal side, 116 climbers who died (51%) were not using supplemental oxygen. On the Tibet side, 41 fatalities (37%) occurred among climbers without oxygen. Combined, 180 of Everest’s 339 total fatalities (53%) involved climbers ascending without supplemental oxygen. Tibet-side climbers tend to be more experienced on average, which likely contributes to the lower proportion of non-oxygen-related fatalities.

Importantly, these death rates include all members and hired support, encompassing incidents at base camp and during route preparation—not only summit attempts. The last time Everest recorded no summits from either side was 1974.

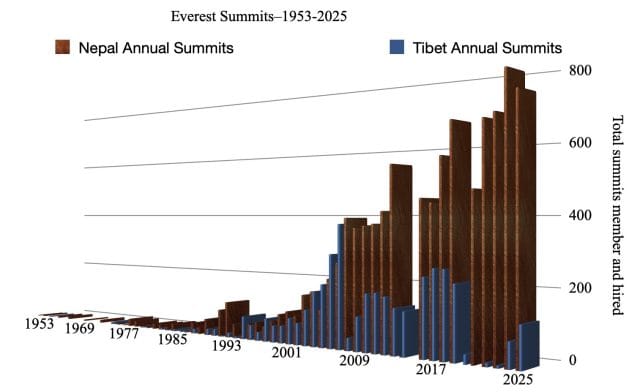

Before 2008, Tibet had been steadily gaining popularity. In the 2000 climbing season, Nepal accounted for 62% of total Everest traffic, while Tibet represented 38%. By 2007, the gap had narrowed further, with Nepal at 59% and Tibet at 41%, suggesting a gradual shift toward the North Side.

That momentum ended abruptly in 2008, when China effectively closed Everest to foreign climbers to facilitate the Olympic torch relay to the summit. The closure prompted many operators to avoid the financial and logistical risk of future restrictions and relocate permanently to the Nepal side. China’s subsequent closure of Everest to foreigners from 2020 through 2023, citing COVID-19, reinforced that shift.

Tibet’s return has been uneven. Recovery has been constrained by China’s variable tourism policies and lingering pandemic effects, and the North Side may never fully regain its pre-2008 share. China generally caps Everest permits at around 300 climbers per season, while Nepal imposes no formal limit. By 2019, the last full season on the Tibet side before the pandemic, Nepal had firmly reasserted its dominance, accounting for approximately 75% of all Everest traffic.

Deaths Ticking Back Up Along with Climbers

Since 2000, Everest has seen an unprecedented surge in climbers. From 2000 through 2025, 15,781 people—6,787 members and 8,994 hired support climbers—climbed above Nepal’s Base Camp, nearly three times the total from the previous 80 years. Between 1921 and 1999, only 5,584 people climbed above base camp.

Over Everest’s full history (1921–2025), 339 people have died on the mountain: 207 members and 132 hired workers, primarily Sherpas. Since the first expeditions in 1922, Everest has averaged about five deaths per year. As participation has grown, the average has increased modestly, rising to roughly seven deaths per year from 2010 to 2025. Note that deaths include climbers on the mountain as well as fatalities at base camp

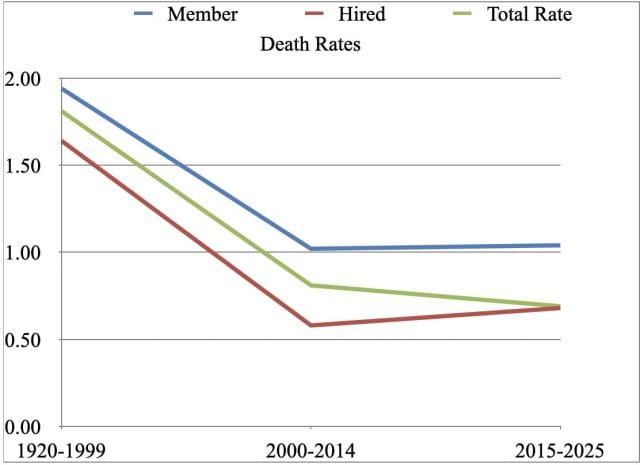

Looking at the most recent decade provides additional context. From 2015 to 2025, 77 people died on Everest, yet the normalized death rate during this period declined to approximately 0.69. Notably, member fatalities (48) exceeded hired-worker deaths (29), reflecting improved safety systems for hired support climbers, higher support ratios, and more effective risk management—even as overall traffic continued to increase.

A small number of catastrophic events disproportionately shape the fatality record. The 2014 Khumbu Icefall serac collapse and the 2015 earthquake accounted for 31 Sherpa deaths, while 2023 recorded a modern high of 18 fatalities. All of these deaths occurred on the Nepal (South) Side and were driven by natural disasters rather than technical failures specific to any route.

Stepping back further, the long-term trend is clear. Between 1920 and 1999, Everest recorded 170 deaths—100 members and 70 hired workers—producing a normalized death rate of approximately 1.81. During this period, climbers pioneered new routes with limited forecasting, rudimentary equipment, and minimal fixed infrastructure. Sherpas were largely employed as load carriers rather than as integral members of summit teams.

The expansion of commercial guiding in the early 2000s marked a turning point. Death rates fell sharply—from roughly 1.8 to about 0.8—as most climbers shifted to the standardized Southeast and Northeast Ridge routes under experienced operators. That trend has continued under newer Western guiding companies and major Nepali operators, even as Everest has entered its busiest era.

It’s still critical to carefully research and select your guide, as I cover in Everest 2024: Season Summary – Everest at a Rubicon. In 2023 and 2024, 23 of the 26 Everest fatalities occurred on expeditions operating at or below the median price, reinforcing a strong correlation between cost, logistics, and safety. While Nepal’s safety reputation suffered after the high-fatality seasons of 2014, 2015, and 2023, the Tibetan side has also experienced deadly years, including six deaths in 2004 and eight in 2006.

Everest has recorded seasons without fatalities — including Nepal in 2010 and Tibet in 2016 — but the last year with no deaths on either side was 1981. It is also important to note that the Himalayan Database calculates death and summit rates based on fatalities occurring above base camp, not solely among summiters.

Standard-98% vs. Non-Standard Routes-2%

One of Everest’s lesser-known statistics highlights just how dominant the standard routes have become. As of December 2025, of the 13,737 total summits, only 187 ascents (141 members and 46 hired climbers) reached the summit via non-standard routes — meaning routes other than the Southeast Ridge or Northeast Ridge. That represents just 1.4% of all summits.

These non-standard climbs accounted for 70 deaths (44 members and 26 hired), representing 21% of all Everest fatalities, despite comprising only 2% of total ascents. In contrast, 78% of all Everest deaths occurred on the standard routes, and the Southeast Ridge alone accounts for 57% of total deaths.

This disproportionate risk helps explain why nearly all commercial operators concentrate on the standard routes, where hazards are better understood, infrastructure is fixed, and rescue access is possible.

Countries with the most non-standard route summits include Nepal (67), the United States (27), Japan (26), South Korea (23), the former USSR (23), and Russia (16). Here is the death summary through 2025:

Reason | Northeast Ridge | Southeast Ridge | Other Routes South | Other Routes North | Total |

Avalanche | 9 | 41 | 13 | 14 | 79 |

Fall | 18 | 34 | 18 | 8 | 78 |

AMS | 12 | 31 | 0 | 5 | 48 |

Exposure/Frostbite | 11 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 26 |

Illness (non-AMS) | 5 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 27 |

Exhaustion | 12 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 32 |

Icefall Collapse | 0 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 19 |

Crevasse | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

Disappearance | 4 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 13 |

other/unknown | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

Falling Rock/Ice | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

Total | 74 | 195 | 34 | 36 | 339 |

Death Rate for those above BC | 0.89 | 0.98 | 2.28 | 1.83 | |

% of Total | 21% | 57% | 11% | 12% |

The End of New Routes?

The last successful new route on Everest was completed in 2009, when a Korean team climbed the Southwest Face. Since then, attempts have been rare.

In 2019, Cory Richards and Esteban “Topo” Mena made a bold attempt on a 6,551-foot direct couloir line on Everest’s Northeast Face from the Tibet side. Starting above Advanced Base Camp (21,325 ft), the line joined a high ridge before continuing up steep terrain toward the summit. After 40 hours on the wall, including an open bivouac, the pair turned back at roughly 7,600 meters, citing deteriorating conditions, accumulated fatigue, and tactical limitations.

Oxygen, Summits, and Deaths

Summiting Everest without supplemental oxygen remains exceptionally rare. Since 1953, only 232 climbers — about 1.7% of all summiters — have reached the top without oxygen.

Of Everest’s 339 total fatalities, 180 occurred among climbers not using supplemental oxygen, but this figure is misleading without context. At least 128 of those deaths happened during route preparation, primarily among Sherpas working lower on the mountain, where oxygen is not used. Major examples include the 2014 Icefall disaster and the 2015 earthquake, both of which occurred below Camp 1.

| Category | Total Attempted | Total Summited | Success Rate | Deaths | Death Rate |

| With oxygen | ~7,246 | ~5,769 | 80% | 75 | 1.03% |

| Without oxygen | ~2,369 | 99 | 4% | 28 | 1.18% |

For members (excluding Sherpas), the data is stark:

Climbers using oxygen were twenty times more likely to summit

Fatality risk without oxygen was slightly higher, though not dramatically so.

Sherpa Support and Summits

Over the past 15 years, Everest has experienced explosive growth in the number of Sherpas reaching the summit, reflecting a fundamental shift in how the mountain is climbed.

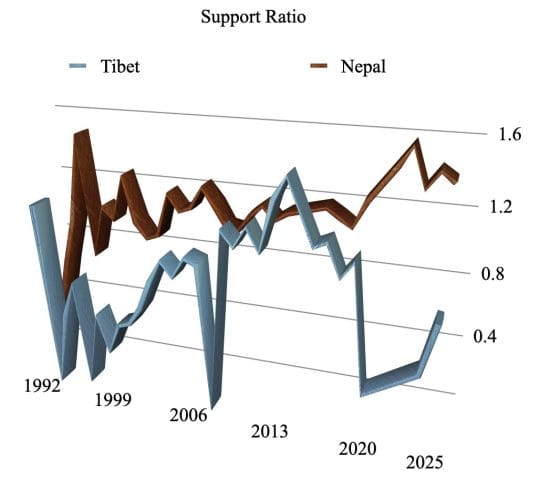

During the early decades of Everest exploration, support ratios were modest. A typical expedition might have one hired support climber supporting three or four professional climbers, roughly 1:4 (25%). By the 1990s and early 2000s, as commercial expeditions expanded, operators increased support to two or three Sherpas for five clients, approximately 3:5 (60%).

Today, the norm on the Nepal side is dramatically different. Two Sherpas per member (2:1, or 200%) is increasingly common. This escalation is driven by several reinforcing factors: a higher proportion of inexperienced clients, heavier personal loads shifted to Sherpas, increased reliance on high-flow supplemental oxygen (up to 8 lpm), and premium operators explicitly marketing 1:1 or even 2:1 “personal Sherpa” support all the way to the summit.

When large-scale commercialization began on the South Side in 1992, 22 Sherpas and 65 members summited, yielding a ratio of 0.34 Sherpas per member. By 2010, that ratio had flipped: 196 Sherpas summited alongside 175 members, producing a ratio of 1.12.

The growth on the Tibetan side has been similarly striking. In 2000, the ratio stood at 17 Sherpas to 38 members (0.45). By 2019 — the last full season before COVID closures — the ratio had more than doubled to 106 Sherpas for 110 members (1.04).

In practical terms, more Sherpas are now summiting Everest than paying clients. Cumulatively, hired support climbers have recorded approximately 7,081 summits, compared to 6,655 by members.

As the accompanying chart shows, the support ratio is rising faster on the Nepal side than on the Tibet side. The notable dip on the Tibetan curve in 2008 corresponds to China’s closure of Everest for the Beijing Olympics, while the flatline from 2019 to 2023 reflects pandemic-era restrictions that eliminated foreign climbers on the North Side.

Everest – An Insatiable Allure

As the data above show, the number of Everest summits has climbed steadily since 1992, when Rob Hall and Gary Ball of Adventure Consultants guided four paying clients to the top, marking the beginning of large-scale commercialization. While David Breashears’ 1985 ascent guiding Dick Bass is often cited as the industry’s starting point, widespread commercial guiding followed quickly, led by pioneers such as Kari Kobler, Todd Burleson of Alpine Ascents International, and K2 Partners.

Despite sharp price increases, Everest continues to attract climbers in ever-growing numbers. Over the past decade, Western-guided expeditions on the Nepal side have raised average prices from approximately $59,000 to $80,000. Nepali operators have also increased their prices from $30,000 in 2015 to around $45,000 today; however, unlike the foreign operators, they often discount heavily — in some cases up to 25%.

On the Tibetan side, prices have risen dramatically, with prices now commonly reaching $95,000. This surge is driven primarily by Western operators marketing “rapid,” “flash,” or “speed” programs, which require substantially higher Sherpa support, logistics, and oxygen loads than traditional schedules. In contrast, Chinese and Nepali operators on the North Side continue to offer expeditions for under $50,000, appealing to more experienced climbers willing to accept leaner support models.

Interest in climbing Everest rose steadily even after disasters like the 1996 disaster, when 15 climbers died, the 2014 Sherpa strike, which shut down the Nepal side after a deadly ice serac collapse, the 2015 earthquake, which ended all climbing on both sides of the mountain, and more recently, when COVID-19 closed Everest to foreign climbers on the Tibetan side from 2020 through 2023, and Nepal closed only in 2020. Yet history shows a consistent pattern: each of these “bad years” was followed by a rebound season with near-record or record summit totals.

Everest appears immune to deterrence. In fact, tragedy, restriction, and rising costs seem only to amplify its appeal. The mountain exerts a paradoxical pull — bad news doesn’t repel climbers; it draws them in, much like bugs to a bright light.

Here’s to a safe season for everyone on the Big Hill.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Follow the 2026 Everest Coverage!

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2026 podcasts on Spotify, Apple, Breaker, Pocket Casts, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

Preparing for Everest is more than Training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are unsure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers worldwide achieve their goals through a personalized approach based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountaineering experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

Everest Pictures and Video

© All content and images owned and copyrighted by Alan Arnette unless noted. Unauthorized use and reproduction are strictly prohibited without specific permission.

A tour of Everest Base Camp by Alan Arnette

Alan Arnette became the oldest American to summit K2 in 2014. He has also made six expeditions to Everest or Lhotse, including a summit of Everest in 2011. He climbs to raise money and awareness of Alzheimer’s disease.

4 thoughts on “Everest by the Numbers: 2026 Edition”

Thanks Alan, Always enjoyed your coverage of the Everest and these statistics. I hope we have a successful and safe season!

Sent from my iPad

This is an incredible post. I love seeing all the statistics in an easy-to read format. Wonderful coverage!!.

I kept trying to comment from the page and was disconnected, so I came back to reply to your post. I was trying to donate to the Cure Alzheimer\’s fund. I clicked the amount. When I clicked DONATE, I got a notice \”THIS PAGE NOT FOUND\”. I tried multiple times.