Welcome to the kick-off for my Everest 2025 coverage! 2025 will be my 25th season of all things Everest: 19 times providing coverage, another four seasons of climbing on Everest, and two years attempting Lhotse.

I summited Everest on May 21, 2011, and have climbed on it three other times (all from Nepal) – 2002, 2003, and 2008, each time reaching just below the Balcony around 27,500′ (8400 meters) before health, weather or my judgment caused me to turn back.

I attempted Lhotse in 2015 and 2016. When not climbing, I cover the Everest season from my home in Colorado as I did in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 and now the 2025 season. In 2020, when both sides of the mountain were closed due to COVID, I did a virtual series, Virtual Everest 2020 – Support the Climbing Sherpas, to raise money for the out-of-work Sherpa community working with nine commercial guiding companies.

If you are one of my millions of regular readers, hello again; if you are new, welcome! I aim to provide insight and analyze the activity without favorites or agendas. I write my posts using sources from the mountain, public information, and my experiences.

I often post as the season starts in early April and ramps up during the intense summit pushes in mid-to-late May. I spend several hours a day creating these updates. You can sign up for (and cancel) email notifications on the lower right sidebar or check the site frequently.

Why This Coverage?

I have one reason for this coverage: Alzheimer’s. I lost my mom, Ida, and four aunts to the disease, which changed my life. Please read more at this link. I hope you value my coverage and consider donating to my chosen non-profits or any organization you prefer. I receive no financial gain from your donations. Click the button on the top right sidebar to donate.

I’ve already posted several Everest 2025 big-picture updates for this season:

- Everest by the Numbers: 2025 Edition – A deep dive into Everest statistics as compiled by the Himalayan Database

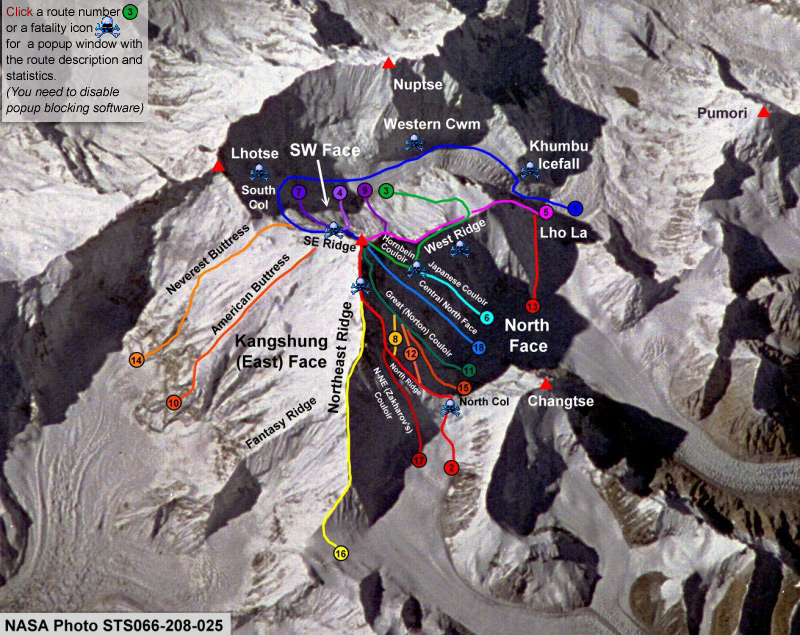

- Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2025 Edition – A detailed look at Everest’s routes, commercial, standard and non-standard.

- How Much Does it Cost to Climb Everest: 2025 Edition – My annual review of what it costs to climb Everest, solo, unsupported and guided.

- Everest 2025: Welcome to Everest 2025 Coverage – an introduction to the Everest 2025 Spring season.

So, let’s see what 2025 has in store for us.

Big Picture

Everest is becoming more expensive, crowded, deadly, and confusing each year. There have been 26 deaths on Everest’s Nepal side in the past two springs. In the 2024 spring season, there were 861 total summits (hired and members from the Nepal and Tibet sides), second only to the 2019 season with 877 summits.

Some operators have increased confusion by enhancing their marketing spin, making it virtually impossible to verify the facts. Thus, I’ve changed my reporting to focus on trends rather than individual operators and climbers. I’ll still mention them when I see something newsworthy, not when it is only noteworthy to the individual or to promote a company’s business.

I expect 700 to 800 summits total from both sides this spring, comprising at least 150 on the Tibet total (members plus hired) and well over 650 on the Nepal side. Even with these numbers, the totals will still lag the pre-pandemic record set in 2019 of 877 total summits, comprising 661 from Nepal and 216 from Tibet. Last year, 2024, 787 summits were from Nepal, and 74 were from Tibet.

The Good News

Nepal will now increase the Everest (and presumably other 8000ers) climbing permit fee from $11,000 to $15,000 in September 2025, which will not impact this Spring season.

- Spring season (March-May): From USD 11,000 to USD 15,000

- Autumn season (September-November): From USD 5,500 to USD 7,500

- Winter (December-February): From USD 2,750 to USD 3,750

- Monsoon season (June-August): From USD 2,750 to USD 3,750

When they go into effect, higher permit fees may impact price-sensitive climbers who choose low-cost guides around $35,000 but likely won’t affect Western climbers who prefer guides costing $75,000 or more. Overall, the impact seems minimal. A more significant change is reducing the Sherpa requirement from one per climber to one for every two, which may affect safety more than it reduces crowds by raising fees.

With lower expedition prices, more people than ever are enjoying mountain climbing. I’m excited to see so many young people try the sport and those a bit older jump in for the first time. Those going to Everest, even just a trek in the Khumbu, Annapurna, or Manaslu circuits, will be treated to amazing sights, a buffet of cultural delights, and life-changing challenges. As I often say, my first visit to Nepal in 1997 changed my life for the better.

Yes, Everest will be crowded, but it’s a big mountain that can handle hundreds of climbers at a time. However, it takes communication and cooperation amongst the guides to prevent overcrowding on any one day.

Some feel the golden age of mountaineering has come and gone and that Everest is now just a tourist trap, complete with escalators and a Starbucks on the summit. However, let me remind you that there are still unclimbed routes on the Big E and ways to climb in “style,” as shown by Jost Kobusch and in 2019 when Cory Richards and Esteban “Topo” Mena made a valiant attempt to send a new route up a 6,551-foot direct line in a couloir, a narrow rock gully, on the Northeast face of Everest. So, if that floats your boat, go for it! See my review of all the routes in Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2025 Edition.

The Not-So-Good News

However, with all this opportunity comes a responsibility that few seem to accept. Trekkers, climbers, government, local and community officials, and guide companies must step up to better care for the environment. This starts with leaving no trace, even a candy wrapper, anywhere but in a trash receptacle. The same goes for solid human waste. Last year, Nepal required all Everest climbers to take their feces down using inexpensive WAG bag ($3 each or lower, under $1 if your guide buys in bulk). That was a good move, but it was just a start and must be enforced on the mountain. That’s critical for those climbing, especially those high on a mountain.

Another opportunity is to improve safety, especially in Nepal, radically. The Chinese authorities require all foreign Everest applicants to have climbed a 6000-meter peak and Chinese nationals to have climbed an 8000-meter peak, driving most Chinese to Nepal, which has no experience requirements. Also lacking is any form of organized rescue service; it’s left up to the operators, and many are understaffed or unequipped to conduct such rescues. Finally, there is a lack of training for guides, including sherpas. At the same time, there has been progress with organizations like the Khumbu Climbing Center, which trains about 50 Sherpas a year. There are not enough qualified support climbers for the growing number of foreigners, many of whom are inexperienced.

Nepal has an opportunity to lead but has failed thus far.

Best Case Weather

The weather is always the wildcard. The best case is predictable weather with sufficient summit days to spread the crowds apart.

With sporadic wind days, last year may have been a bit more complicated than usual. I used to call the weather windows “Summit Waves,” but they were more like Tsunamis with the occasional puddles last year. Usually, we see hundreds of summits each day, but in 2024, it was as few as two people for the entire day.

Unbelievably, around 50 people turned back last year after trying to summit on May 12th with winds forecasted to gust to 50 mph. The top limit for the best-run teams is 30 mph. Why expedition leaders choose to put their clients in obvious danger is beyond me. That said, it’s well documented that some operators have a different risk tolerance than others.

Professional forecasters like Chris Tomer, Michael Fagin, Marc DeKeyser, and Meteoexploration provide human-curated forecasts for the best teams. Other teams use free forecasts from the Internet.

Definitions

Before we get going, let’s define a few terms. I’ll leverage some of what the Himalayan Database uses in its reporting. Refinements to these definitions are welcome:

- Members: anyone who pays to be guided, including those who only use base camp services and climb independently above base camp. More information.

- Hired/Guides: Anyone paid to climb Everest. Hired include Sherpas, Tibetans, and other ethnicities, plus Western guides.

- More information.

- Western: Any member, hired guide or company not based in Nepal or Tibet

- Nepal Side: Nepal’s jurisdiction of Everest’s south side, the Southeast Ridge or South Col.

- China/Tibet side: China’s jurisdiction of Everest’s north side, aka the Northeast Ridge or North Col. I usually use Tibet, not China.

- Solo Climber: Anyone who never touches a ladder or fixed rope, carries all their kit, sets up camps, cooks all their own meals above base camp, and is not part of a team and has no support from a teammate or “hired” aka Sherpa or Tibetan. More information.

- Independent Climber: Anyone who is part of a team but climbs alone without Sherpa or Tibetan support. They use infrastructure such as ladders and ropes, and the logistics of their team to move from base camp to high camps.

- No O’s: Anyone who never uses supplemental oxygen, including sleeping or during the descent. Less than 3% of all Everest summiteers have not used supplemental oxygen. Of the 327 Everest deaths since 1924, 178 died while not using supplemental oxygen, or 54%.

- Acclimatization: Multiple climbs to ever higher camps, returning to lower camps to sleep to acclimate their bodies to the reduced level of oxygen molecules in the air. More information.

- Pre-Acclimatization: Weeks before arriving on the mountain, the climber will sleep at home in an altitude tent connected to an altitude generator that reduces the percentage of oxygen in the air. Most climbers on expeditions under three weeks, i.e., “Flash or Rapid,” almost always use this technique. Some studies show climbers can acclimate to as high as 7,000 meters. More information.

- Rotation: Climbers use expedition or siege-style climbing to establish multiple camps at ever higher elevations, returning to lower camps to sleep to acclimate their bodies gradually. Today, teams will perform two to five rotations. Some will reduce the number on Everest by climbing lesser peaks such as Lobuche or Island Peak.

- Alpine Style: The mountain is climbed in a single push without O’s, support from other climbers, i.e., Sherpas, and no use of fixed ropes or established camps. There are no “acclimatization” rotations. The climber carries all supplies–food, stoves, fuel, tents, etc. They leave no trace on their route other than footprints. May climb in pairs or a small team. There are virtually no alpine climbs of Everest these days.

- Expedition, aka Siege style: The mountain is climbed in stages, with multiple “acclimatization” rotations to ever higher camps. hired climbers usually stock siege-style Camps, but not always. Steep sections have fixed rope—ladders are placed across crevasses or in vertical sections. Virtually all Everest climbs are in expedition style.

- “Conquering the Mountain“: No one conquers a mountain; they climb it and return home.

- Leave No Trace: Absolutely nothing is left on the mountain from the climb, including solid human waste, oxygen bottles, ropes, tent fragments, rubbish, or anything human-made. More information.

2024 Review

Everest 2024 might be remembered for summits, politics, deaths, ignored rules, near misses and disturbing allegations of sexual misconduct. Putting all this in a headline is challenging, but I believe the Everest guiding industry is at a Rubicon–a point of no return.

Not to be lost in this mix is the joy and satisfaction felt by hundreds of summiteers. They worked and trained diligently to celebrate standing on the top of the world for only a few minutes. It’s funny how you can work so long for a goal, and the moment is over in a blink, but the memory lasts a lifetime—well done to all who summited, to those who showed up.

Once again, the Sherpas dominated the mountain with impressive altitude performance. The Himalayan Database shows that between 1950 and 2024, 6,593 Sherpas have summited Everest compared to 6,285 members, and that gap is growing each year. However, more foreigners have died than Sherpas, 203 compared to 129.

We may have heard the last chirps from Everest’s “canary in the coal mine.” Between the difficulty of getting the fixed ropes through the Icefall and the collapse of a cornice at the Hillary Step, climbing the reliable Southeast Ridge route could be at risk. The cause is most probably a warming environment. As for summits, the Himalayan Database reported in December 2024, based on numbers reported by the Nepal government:

Summits and Deaths for 2024

| NEPAL | TIBET | TOTAL | ||

| Members | 319 | 51 | 370 | 43% |

| Hired | 468 | 23 | 491 | 57% |

| TOTAL Summits | 787 | 74 | 861 | |

| % of Total | 91% | 9% | ||

| Summit Rate | 68.25 | 67.27 | 68.17 | |

| Member Deaths | 6 | 0 | 6 | 61% |

| Hired Deaths | 2 | 0 | 2 | 39% |

| TOTAL Deaths | 8 | 0 | 8 | |

| % of Total | 100% | 0% | ||

| Death Rate | 0.69 | 0 | 0.63 |

Price matters when it comes to safety. In 2023 and 2024, 23 of the 26 deaths were climbers with operators charging under the median price. Continue reading about Everest 2024

Follow the 2025 Everest Coverage!

2025 Everest Outlook

As of this post, the Icefall Doctors have arrived at Everest Base Camp on the Nepal side to begin setting the fixed lines from EBC to Camp 2. After that, one of the commercial teams, 8K Expeditions, will fix the route to the summit, opening it to all climbers on the mountain. The Tibet side usually lags behind Nepal, with teams arriving later. The climb on that side is slightly shorter due to driving, not trekking, to base camp and having higher camps.

I suspect 2025 will be another busy year. First, there is the insatiable lure of Everest, as has been the standard since 2013, with droves of inexperienced climbers drawn by “no-experienced required” low-cost operators. However, 2025 will be different, with the north side reopening to foreigners and the last year before Nepal raises permit pricing by 36%.

The climbing headline is we can expect a couple of interesting climbs, like speed climbs or using Nobel gases to shorten the expedition length. Also, more experiments with oxygen delivery systems might be conducted, such as using a nasal cannula or a lightweight tube with prongs that fit inside the nostrils instead of a full face mask, especially while sleeping above Camp 2 or the North Col. Overall, 99% of activity will be traditional commercial teams guide clients on the two commercial routes. Look for the Sherpa–to–client ratio to continue increasing with as many as three Sherpas supporting one client for some teams.

The financial headline for 2025 is that prices continue to increase for all Western and some Nepali operators on the Nepal side and stay flat or slightly lower for most Tibetan-side operators. The increases are due to inflation, labor wage increases, higher pay for Sherpas with IFMGA certification, more Nepalese regulations around minimum salaries and insurance, and a strong client demand environment.

Several companies now offer luxuries never imagined for mountain climbing. These add-ons come at a price, and the upper end can be as high as $200,000 and even $1 million. Often, they cater to wealthy individuals who have more money than time and seek to summit as quickly as possible and return to work.

So, do you have to be rich to climb Everest in 2025? With Nepal’s strong tourism business and high demand, Nepali companies will still deal but not as aggressively as in the prior years. You can get on a low-end, essential services-only trip for $30,000. As for dealing with foreign operators, don’t count on a significant discount. It’s customary to offer a little off if you pay a year in advance, but that’s about it. They fill their teams months in advance, so there’s little incentive to discount.

The following chart breaks down the current MEDIAN prices (midpoint for prices with half above and half below this price) by style and route. Foreign operators have actual costs operating in Nepal that the locals don’t, such as buying permits for Western guides, thus the significant difference in the prices.

| Nepal Side 2024 | Nepal Side 2025 | % Change | Tibet Side 2024 | Tibet Side 2025 | % Change | |

| Nepali Guide Service | $40,049 | $44,086 | 9.2% | $47,000 | $47,000 | 0% |

| Foreign Guide Service with Sherpa Guide | $51,513 | $52,967 | +2.7% | |||

| Foreign Guide Service with Western Guide | $73,000 | $76,600 | +5.8% | $75,000 | $70,000 | -5.9% |

As for safety, people die on both sides. Most of the deaths these days are caused by inexperience and not having a guide who “manages” your climb. However, choosing a competent guide could save your life.

Tibet

For the first time since 2019, the Chinese will run their side like they had pre-pandemic. From 2019 to 2022, only Chinese scientists and technicians could climb, and they installed and maintained a weather station near the summit. Last year, in 2024, they opened Tibet to foreigners, but a delay in issuing tourist visas prevented most commercial teams from climbing.

Unlike Nepal, which has no limits on the number of permits issued for Everest, China has a maximum of 300 annual permits for hired and members. The only time there were more summits than 300 was in 2007, when 197 members, supported by 178 hired, reached the top, totaling 375. Since 2010, the median has been well under the quota of 153 people, so this should not be an issue in 2025. However, we may see the north-side crowds increase next year, 2026 when Nepal’s price increase goes into effect for Everest.

Only a few Western companies, including Alpenglow Expeditions, Furtenbach Adventures, Kobler & Partner, and Summit Climb, regularly, but not always, guide on the Tibet side. Most established Nepali and Tibetan operators run expeditions, like Lhasa-based Yala Xiangbo Mountaineering Adventure Co., Climbalaya and Seven Summits Treks.

There are a few new rules for this season, but as usual, China does not publish them publicly; it only announces them to selected operators. For example, in 2024, they announced that all climbers must use supplemental oxygen on all three of their 8000-meter peaks, but not every operator received that guidance.

Nepal

Look for foreign permits to be above or close to last year’s record 478 issued to members from 65 countries. Last year’s largest countries were China–97, the U.S.–89, India–40, Canada–21, Russia–20, the U.K.–19, and Nepal (non–Sherpas)–16. Permits were issued to 102 female members and 376 males. There were around 667 summits on the Nepal side. More Sherpas, 378, summited than clients, 277, according to the Himalayan Database, for a support ratio of 1:136, which is increasing each year thus adding to the crowding. The Nepal government collected over USD 5 Million in permit fees.

Trash continues to be a problem, especially at the high camps, particularly at Camp 4 on the South Col. Perhaps all expeditions will require WAG bags this year.

Everest Guides

A significant shift in the guiding industry began around 2013. That was when the Nepal expedition operators started to market Everest expeditions and the other 8000ers with low prices and well-designed websites. Unlike foreign guides, Nepali companies do not have to pay permit fees for Nepali guides and traditionally pay lower wages to their staff. These savings are passed on to their clients through lower prices.

This business model attracted a new demographic of price-conscious climbers, mainly from China and Southeast Asia and many from India. One of their marketing promises was, “No experience required; we’ll teach you everything you need to know on the mountain.” This business model has been very successful, albeit with proportional deaths.

Who guides on Everest continues to consolidate. Long-time companies still run yearly expeditions. These include Nepali operators, like Asian Trekking and Western guides–Alpine Ascents International, Summit Climb, International Mountain Guides, and Himex (now sold and inactive on Everest). These outfits created the Everest climbing industry. They are now joined by relatively recent (last ten years) newcomers like Climbing the Seven Summits, Furtenbach Adventures, Madison Mountaineering, and Mountain Professionals. These companies’ prices range from $54,000 (IMG-1:1 Sherpa Guided) to $130,000 (CTSS-Western Private Guide).

The most prominent Nepali-owned operators may have over 100 members compared to 20 or fewer for Western guides. They include 8K Expeditions, 14 Peaks Expeditions, Asian Trekking, Elite Expeditions, Imagine Nepal, Pioneer, and Seven Summits Treks. Smaller Nepali companies are Arun Treks, Ascent Himalaya, Climbalaya, Satori Adventures, and Thamserku. Today, there are around 2,000 “trekking” agencies registered in Nepal.

The best operators use professional guides with IFMGA certification. They charge more for this expertise, but it could be a life and death difference if you encounter an emergency like injury or altitude issues. Remember that not everyone called a “guide” is a qualified guide. Each company can call their staff whatever they like.

2025 Demographics = Crowds

Because of the discussed dynamics, I expect another year of crowds on Everest. Crowding is a disturbing trend that began several years ago in earnest. Low prices continue to attract climbers with little experience, as shown by the nightmare line of people between the South Summit and the Summit in 2019. The members struggled with the altitude and went too slowly, and the guides did not manage the clients and let them clog up the system. This scenario was like following a frustratingly slow driver on a one-way mountain road with steep drop-offs on both sides—no way to pass. Nothing has changed since then, and it won’t surprise me if we see something similar this year if there are only a few suitable summit days.

The best guides will use professional weather forecasts to select a suitable weather window of several days when the summit winds are under 30 mph. They will let the rush that always occurs just after the ropes are fixed to the summit subsidize before going for their summit push. The best companies have used this strategy for years, with excellent summits and safety success.

Bugs to a Light

Everest has an immutable attraction that is oddly perverse. When there is a record number of deaths, the following season has more climbers than the previous deadly one. For example:

- 2006: 11 deaths, 494 summits

- 2007: 7 deaths, 634 summits

- 2012: 10 deaths, 581 summits

- 2013: 8 deaths, 684 summits

- 2014*: 16 deaths, 134 summits

- 2016: 5 deaths, 679 summits

- 2023: 18 deaths, 668 summits

- 2024: 8 Deaths, 787 summits

- 2025: ? Deaths, ? summits

* 2014 season ended early when 16 Sherpas died in the Icefall. 2015 closed because of the earthquake.

We’ll see what 2025 brings, but history suggests it will be a big year, especially with the North open and prices increasing in 2026. The bottom line is that it is more crowded than ever, so guides must coordinate schedules more tightly.

More Deadly Than Ever

335 people, 217 members, and 110 hired (Sherpas) died on Everest from 1921 to 2024. Since the first attempt in 1922, an average of 5 people have died each year. From 2010 to 2024, deaths rose dramatically to an average of 8 annually. The 31 total Sherpa deaths in 2014 from the Serac release onto the Icefall and the 2015 earthquake drove up the average death rate, as did the record 18 deaths in 2023. All of these deaths were on the Nepal side of the mountain.

Digging deeper into each period, the death rate from 1921 to 1999 was 1.80, with 170 people dying, 100 members, and 70 hired. More members died than hired due to pioneering new routes, and the Sherpas were primarily used for load carrying. When commercialization grew in the early 2000s, the death rate drastically declined from 1.80 to 0.80. There were fewer new routes, and most of the traffic took place on the Southeast or Northeast Ridges.

2023: 16 Deaths

2023 was the deadliest year ever for Everest climbers, with eighteen deaths. While deaths regularly occur on Everest, with an average of four each year, I believe that ten of the eighteen deaths in 2023 were avoidable. Five of the deaths happened on the descent after summiting. Using the cause of death listed in the Himalayan Database, we can see that many climbers died from altitude-related issues:

- 8: Acute Mountain Illness (AMS)

- 3: Fall

- 3: Missing/Disappeared

- 3: Icefall Collapse (Sherpas route fixing)

- 1: Illness (non-AMS)

These are the deaths during the 2023 spring season. I marked with an “*” that I believe were avoidable by turning back as soon as they got in trouble. That said, every situation is different, as deaths high on Everest are rarely investigated for cause and prevention.

1-3. On April 12: Pemba Tenjing Sherpa (Tesho, Khumbu), 31, Lakpa Rita Sherpa (Tesho, Khumbu), 24, and Dawa Chhirri (Da Chhiri) Sherpa (Phurte), 45, all working for Nepali operator Imagine Nepal, died when the upper section of the Icefall collapsed

4. May 1: American Jonathan Sugarman, 64, died at Camp 2 from AMS climbing with American operator International Mountain Guides (IMG) 5. May 16: Phurba (Furba) Sherpa(Makalu-9), 41, died from AMS near Yellow Band above Camp 3. He was part of the Nepal Army Mountain Clean-up campaign with Peak Promotion.

*6. May 17: Moldovan climber Victor Brinza died from AMS at the South Col with Nepali operator Expedition Himalaya.

*7. May 18: Chinese Xue-bin Chen, 52, died from a fall near the South Summit with Nepali operator 8K Expeditions

*8. May 18: Indian Suzanne Leopoldina Jesus, 58, intended to climb Everest but left EBC ill and died in Lukla, so it is not technically a climbing death. Her agency was Glacier Himalaya Treks.

*9. May 19: Malaysian Awang Askendar Ampuan Yaacub, 55, got above South Summit and died from AMS. He was climbing with Nepali operator Pioneer Adventure.

*10. May 19: Indian Singaporean Shrinivas Sainis Dattatray, 39, is presumed dead from a fall but is missing. His agency was Seven Summits Treks.

*11. May 19: Malaysian Muhammad Hawari Hashim, 33, is presumed dead from a fall but is missing. His agency was Pioneer Adventure.

12. May 19: Australian Jason Bernard Kennison, 40, died near the Balcony from AMS. He was with Asian Trekking. 13. May 23: Ang Kami Sherpa(Patle-1), 32, cook staff, died at Camp 2 from a fall. He worked for Peak Promotion.

*14. May 24: Indian Swapnil Adinath Garad, 36, died from AMS. His agency was Asian Trekking.

15. May 24: South African/Canadian Dr. Petrus Albertyn Swart, 63, reportedly died from AMS after turning back at the South Col. Climbing with Madison Mountaineering.

*16. May 25: Nepali Ranjit Kumar Shah, 36, is presumed dead near the South Summit but is missing. His agency was Annapurna Treks.

*17. May 25: Lakpa Nuru Sherpa (Phakding), 41, is presumed dead near the South Summit but is missing. His agency was Annapurna Treks.

*18. May 25, Hungarian Szilard Suhajda, 40, climbing alone with no Sherpa support and without supplemental oxygen, went missing near the Hillary Step and is presumed dead. His agency was Asian Trekking.

Age is a significant factor in 8000-meter climbing deaths. In 2023, five of the dead, 27%, were older than 50. Between 2000 and 2023, members on the Nepal side between 50 and 60 years old have a death rate triple that of the 40-50 age range: 1.64 compared to 0.55, and those over 60 swell to a rate of 2.9.

2024: 8 Deaths

All eight of the 2024 deaths were clients of Nepali operators.

Everest Eight Deaths

- May 28 – Indian Banshi Lal, 46, died in a Kathmandu hospital after being evacuated from Everest with AMS. He was climbing with 8K Expeditions.

- May 23 – Nepali (not a Sherpa) Binod Babu Bastakoti, 37, died near the south Col after summiting and climbing with Yeti Adventure.

- May 22 – British Daniel Paul Paterson, 40, is missing near Hillary Step collapse after summiting with Pastenji Sherpa and climbing with 8K Expeditions.

- May 22 – Pastenji Sherpa, 23, is missing near Hillary Step collapse after summiting with Daniel Paterson and climbing with 8K Expeditions.

- May 22 – Kenyan Cheruiyot Kirui, 40, died above the Hillary Step, climbing without Os and with Nawang Sherpa, with Seven Summits Treks.

- May 22 – Nawang Sherpa,44, is missing above the Hillary Step, climbing with Cheruiyot Kirui and for Seven Summits Treks.

- May 13 – Mongolian Usukhjargal Tsedendamba, 53, died on the SE Ridge after summiting, climbing with Usukhjargal Tsedendamba, and logistics by 8K Expeditions.

- May 13 – Mongolian Prevsuren Lkhagvajav, 31, died on the SE Ridge after summiting, climbing with Usukhjargal Tsedendamba, and logistics by 8K Expeditions.

Lhotse One Death

- May 21 – Romanian Gabriel Tabara, 48, was found dead inside his tent at C3 attempting Lhotse. He was climbing with Makalu Adventure.

Deadly Icefall?

Sadly, it’s not unusual to have deaths in the Khumbu Icefall; however, while the Icefall is a dangerous section of the Southeast Ridge, aka South Col route, more people (clients and Sherpas) die elsewhere on the mountain. I used the Himalayan Database and searched for deaths between 5400 and 5940 meters – the altitude range of the Icefall. Of the 225 deaths on the Nepal side, 43 occurred in the Icefall. Virtually all these deaths were Sherpas ferrying loads to camps in the Cwm and above.

- 21 – Avalanche (16 in 2014 from Everest West Shoulder from the hanging seracs)

- 17 – Icefall Collapse (Similar to what we saw in spring 2023, taking three Sherpas)

- 3 – Crevasse

- 1 – Illness

- 1 – AMS

Deadly Guides?

Similar to 2019, when 21 people died across Nepal’s eight 8000-meter mountains, in 2023 and 2024, there was a correlation between deaths climbing with operators who charged less than the median. I describe these cost metrics in How Much Does it Cost to Climb Everest: 2025 Edition

In 2023, fifteen of the eighteen deaths were with Nepal operators. In just two years, twenty-three people who died were associated with Nepali mountain guide companies. That’s 88% of the total for the two years. These teams had deaths in the last two years.

- 8K Expeditions: 6

- Asian Trekking: 3

- Imagine Nepal: 3 (Sherpas)

- Pioneer Adventure: 2

- Seven Summits Treks: 3

- Annapurna Treks: 2

- Peak Promotion: 2

- Expedition Himalaya: 1

- Glacier Himalaya Treks: 1

- International Mountain Guides: 1

- Madison Mountaineering: 1

- Makalu Adventure: 1

- Yeti: 1

The same operators accounting for most deaths will return in 2025, so we will see if anything changes. The top years for deaths on both sides, by all routes, were 2023 (18), 2014 (16), 1996 (15), 2015 (13), 2019 (11), 1982 (11), and 1988 (10).

Rules

Rules, new rules, ignored rules and silly rules.

In May 2024, Nepal’s Supreme Court issued a series of well-intended but vague rules that potentially will join a long list of ignored rules. The largest and most well-connected operators have long learned that doing whatever they want has no consequences other than making more profit.

As expected, the new rules announced earlier had little impact. For example, the ban on helicopters for non-emergencies was simply ignored. In an IG post, Eduard Kubatov explains that climbers turned back on their summit push due to the forecasted high winds, and some took helicopters back to EBC. Though prohibited, it’s become common for climbers who summit to fly off the mountain from Camp 2, thus avoiding the Icefall. I believe they do not deserve a summit certificate since they didn’t complete the round trip from EBC to the summit to EBC.

The Nepal Supreme Court’s “new” rules mainly were reruns of previously issued rules that were largely ignored:

- Issue climbing permits only after specifying the number of climbers and the capacity to accommodate the climbers.

- All mountain climbing team members compile a comprehensive list of items they plan to take with them. The list should be recorded at the departure point before the ascent begins, and upon their return.

- The SC has urged the government to focus on mountain protection and cleanliness.

- Coordinate garbage and corpse management in mountainous areas, establish a monitoring team (ranger) comprising experienced mountain climbers, and ensure adequate wages, accident insurance, and compensation for individuals engaged in the cleaning campaign.

But these were not the only rules issued last season. In February of 2024, the Khumbu Pasang Lhamu Rural Municipality, the governing body charged with managing Nepal’s Everest Base Camp (EBC), announced new rules without warning or apparently investigating their feasibility. Some addressed trash, others EBC sprawl, and others luxuries.

- Climbers would be required to haul their feces off of the peak using WAG bags

- Size limitations on square (box) and dome tents, plus no attached toilets

- No business, e.g., massage services, bakeries, stores and the sort

- Helicopters are banned from ferrying gear to camp

- Visitors and trekkers are banned from sleeping at EBC camp

- Every climber is required to carry down at least eight kilograms (17.6 pounds) of garbage from the mountain

The latest rules effective in September 2025 include:

- No solo climbers

- A 2:1 sherpa-to-climber ratio

- Permit increase from $11,000 to $15,000 per climber

- Sherpa’s base pay increased to US$8.64 per day

- Sherpa’s life insurance increased to US$107.94

I’ve been tracking these rule announcements for over ten years, and it’s fascinating to see repeats. Still, the common theme is virtually none are ever enacted or enforced because of the instability of the Nepal government and the revolving door of Ministers who run the Ministry of Tourism. This eye chart shows the ones announced and often promoted by the mainstream press; however, virtually none were ever enforced. I have a red check by the ones I believe were implemented. Click the chart to enlarge it.

Summit Statistics through December 2024

Another popular post is Everest by the Numbers: 2025 Edition

The Himalayan Database reports that 7,269 different climbers have accomplished 12,884 summits of Everest across all routes. Among those climbers, 1,670 members and 2,003 Sherpas have reached the summit multiple times, accounting for a total of 4,620 summits. Women members have achieved 962 summits.

Summits

The Nepal side is more popular, with 9,156 summits compared to 3,728 summits from the Tibet side. Only 229 climbers summited without supplemental oxygen, about 1.7%. Only 35 climbers have traversed from one side to the other. Member summit success stands at 39%, with 5,899 who attempted to summit, making it out of 14,496 who tried. About 66% of all expeditions put at least one member on the summit.

Kami Rita Sherpa (Thami) holds the record for most summits at 31, with Paswang Dawa (PA Dawa) Sherpa of Pangboche close behind with 27 summits. Brit Kenton Cool has 18 for a non-Sherpa record. Eleven Sherpas have 20 or more summits.

One hundred and one Sherpas have summited Everest 10 or more times. Member climbers from the USA have the most country member summits at 1,078, followed by China at 683, India at 605, and the UK at 560.

Deaths

As for Everest deaths, 335 people (203 Westerners and 129 Sherpas) died from 1922 to December 2024. These deaths account for about 2.7% of those who summited, resulting in a death rate of 1.11% among those who attempted to reach the summit. Westerners die at a higher rate of 1.36%, compared to Sherpas at 0.84%.

Descending from the summit is deadly, with 74 deaths, or 22% of the total fatalities. Female climbers have a lower death rate of 0.81% compared to 1.14% for male climbers, and 14 women have died on Everest. Everest. The Nepalese side has seen 9,156 summits with 225 deaths through December 2024, or 2.5%, representing a rate of 1.12%.

One hundred thirty deaths, or 27%, did not use oxygen. The Tibet side has witnessed 3,728 summits with 98 deaths through December 2024, or 2.6%, a rate of 0.98%. Thirty-eight individuals died without using oxygen.

Countries with the most deaths among climbers include India at 28, the UK (19), Japan (19), the US (17), and China (12), with South Korea at 11. Nepal has the absolute highest number of deaths at 135, dominated by Sherpas. Most bodies remain on the mountain, but China has removed many from view on its side. The top causes of death are avalanches (77), falls (75), altitude sickness (45), and exposure (26).

Latest: Spring 2024

In 2024, 787 summits were made, including 74 from Tibet. All but 5 used supplemental oxygen. Eight Everest climbers died. 68% of all attempts by members were successful. Of the total, 73 females summited

Everest compared to the Other 8000ers

Everest is becoming safer even though more people are now climbing. From 1923 to 1999, 170 people died on Everest with 1,170 summits, or 14.5%. But the deaths drastically declined from 2000 to 2024, with 11,714 summits and 165 deaths, or 1.4%. However, four years skewed the death rates, with 17 in 2014, 14 in 2015, 11 in 2019, and a record 18 in 2023.

The reduction in deaths is primarily due to significantly higher Sherpa support ratios, improved supplemental oxygen at higher flow rates (up to 8 lpm), better gear, accurate weather forecasting, and more people climbing with commercial operations. Of the 8,000-meter peaks, Everest has the highest absolute number of deaths (member and hired) at 335 but ranks near the bottom with a death rate of 1.11.

Annapurna is the most deadly 8,000er, with one death for about every fifteen summits (73:514) or a 3.30 death rate. Cho Oyu is the safest, with 4,158 summits and 52 deaths, or a death rate of 0.54, with Lhotse next at 0.61. Of note, 81 Everest member climbers out of 206 member deaths died descending from the summit, or 39%. K2’s death rate has fallen dramatically from the historic 1:4 to around 1:8, primarily due to more commercial expeditions with large Sherpa support ratios.

My Coverage is Changing

I no longer regularly report on individuals or teams because the information is complex to verify for accuracy in this age of social media and self-promotion. Thus, my coverage shifted a couple of years ago to highlights, the big picture, and trends.

You will not read of death first on my site out of respect to families and the high rate of inaccurate information, especially for breaking news, which is almost always incorrect. I report on what I see without fear or favor and do my best to be as accurate as possible, a standard I have kept for over twenty years.

Follow the 2025 Everest Coverage!

Here’s to a safe season for everyone on the Big Hill.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2025 podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Breaker, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

Preparing for Everest is more than Training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are unsure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers worldwide achieve their goals through a personalized set of consulting services based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountain experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

Everest Pictures and Video

© All images owned and copyrighted by Alan Arnette unless noted. Unauthorized use and reproduction are strictly prohibited without specific permission.

A tour of Everest Base Camp

6 thoughts on “Everest 2025: Welcome to Everest 2025 Coverage”

Love this

Good morning Alan,

I have done the base camp trek, many years ago and love updates on the yearly climbs. Unfortunately it’s now become hard to find the information with out paying increasing fees. Would love to receive emails. Thankyou Sir

Hey id love to read ur blog this season but there must be some sort of pop-up auto scrolling to the bottom and I can’t over ride it

Hi! I am a teacher who teaches middle school kiddos. We are reading the book PEAK and would love to be included in this years climb. I want to students to feel involved as we read out novel about a boy who climbs Mt. Everest!

Your Everest 2025 coverage is insightful and impactful, highlighting key issues like overcrowding, safety, and environmental responsibility. The shift to trend-focused reporting is commendable, and your advocacy for responsible climbing is essential. Keep leading the conversation!

Your data regarding the mount Everest is awesome …

Comments are closed.