Mostly, local Nepalese media are promoting a new route bypassing the infamous Khumbu Icefall, claiming it to be shorter, faster, and safer, retracing the original path used by the British 1953 expedition that accomplished the first Everest summit. These articles seem to confuse a new route with an old trekking route reopened, and may not have thoroughly fact-checked some of the performance claims.

While the overall press is limited and has not gone mainstream, the facts are not as simple as “new summit route.” I believe commercial operators will rarely use the route on Nuptse’s flanks to bypass the Icefall, as it is too difficult for today’s average Everest climber. Still, it may be used by a few who have the skills and desire to avoid the Icefall.

Let’s take a look at the proposed new route, its history, then fact-check some of the claims, including that the Icefall is the most dangerous section when climbing Everest, and finally, a look at what today’s climbers can do if they have Icefall concerns.

Big Picture

He’s not the first with this idea, but French alpinist Marc Batard, 70, has been trying for several years to define and build a route that bypasses the Khumbu Icefall by climbing on the flanks of Nuptse, the peak to the climber’s right as they ascend the Icefall.

Not a NEW Idea!

Route Details

So, back to Batard, in 2021 and 2022, with a team of four French climbers and two Sherpas, they scouted and built sections of the route using a “via ferrata” system of permanent steps, belays, and fixed ropes on the rock face.

The team has fixed a new 700-meter section with 1,000 meters of rope and 10mm screw bolts, according to Nepal News reports. AHN reported, “According to the French mountaineer Antoine Erol, out of 270 fixed steps as the base of safety ropes and ladders, 220 steps are already installed. He estimated that the completion of the remaining 50 steps will be done by March-April of 2026.”

The route starts from Gorak Shep Village (5,140m/16,942 feet), the last village with teahouses and meals before Everest Base Camp at the foot of the Khumbu Icefall. The Nepalese government has been investigating moving Everest Base Camp to Gorak Shep for a few years, citing environmental issues with EBC sitting on the Khumbu Icefall, but the proposal has lacked support from the major guiding companies.

From Gorak Shep, the route crosses old moraine and a former lakebed associated with the Khumbu Glacier, before ascending an old trail toward a peak that Batard named, Sundar Peak (5,880m). It then reaches the Nuptse ridge for a straightforward walk before requiring an abseil/rappel descent of several hundred meters into the Western Cwm, meeting up with the traditional Everest Camp 1 (6,065m).

Batard and other promoters cite the need for the new route to avoid the Icefall by taking a shorter (new route is roughly 200 meters longer than the Khumbu Icefall route), safer (not clear since it’s never been used by commercial guides) and faster (unlikely due to climbing up steep rock walls on steps, using a via feratta, and having to rappel down hundreds of meters which traditionally creates a roadblock when climbers queue for a slot on the rope(s).

For the 2026 season, Batard, along with fellow French climber Antoine Cayrol and Kaji Sherpa, plans to finish the route and demonstrate its commercial viability.

It is estimated that it will cost about 400,000 US Dollars to construct this route fully. So far, $300,000 has been spent, and the remaining $100,000 is being collected from primarily French donors. The Nepalese government has sent mixed signals on funding and support for the project. source

However, a recent report noted that “The Government of Nepal has officially granted permission to Speed Kaji Sherpa and Marc Batard to lead this initiative. The Cabinet of the Federal Government approved the project on 21 Poush 2081 (early January 2025) and issued written authorization for route development up to 6,100 meters elevation. While the Nepalese government is providing official and logistical support, the project’s financial backing comes mainly from French institutions and donors.”

A point of confusion in many media reports is a statement like “It will be the first new path to the summit from Nepal since Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary established the current route with their historic 1953 ascent.” I believe they are not referring to a new summit route but rather the trek from Jiri to Lukla that the early expeditions used, since air travel between Kathmandu and Lukla was not available until 1964. The new Batard route joins the traditional Southeast Ridge route to the summit from Camp 1 in the lower Western Cwm.

Guide’s Opinion

I asked the founder of one of the leading guide companies, Climbing the Seven Summits, Mike Hammil, if he planned to use it.

Honestly, I haven’t considered Marc’s route because it is so close to Nuptse on the rocks. This approach seems unnecessarily exposed to rock and ice falling directly off the Nuptse face, where we see constant avalanches, for a much longer period than our normal route. The lower icefall route is reasonably fast and efficient and less exposed to Nuptse. Last year the Icefall Doctor’s route used the rocks for a bit, but further away from Nuptse and in a more protected area.

Above the rock section it makes sense to trend climbers left up the gut of the glacier where it is easier to follow safer terrain. I don’t know if Marc’s route just stops once it’s past the rock section, if it ties into our normal route, or continues to hug Nuptse?

Each year we look closely at the Icefall Doctors route in terms of safety, efficiency and speed through objective hazards and I think they do a great job and can’t imagine how Marc’s route could be better? Unless I saw compelling evidence for it (& I’m open minded to considering it) I would plan to stick with the Icefall Doctor’s route.

We are also a bit unique in that we’re the highest camp on the glacier so it is very direct and fast for us to jump onto the normal icefall route right from our camp. To make use of Marc’s route I believe we would need to backtrack down the glacier to the start.

And from Pemba Sherpa of 8K Expeditions:

I do not support this. Rocky, steep and risk of avalanche. Sherpa guides community does not accept this route

History

George Mallory, while seeking a route to the summit of Everest, is said to have sighted the Icefall in the early 1920s and described it as “terribly steep and broken … all in all, the approach to the mountain from Tibet is easier,”5 thus shifting his efforts to Tibet. It wasn’t until 1950 when Charlie Houston and Bill Tilman led a British reconnaissance team to scout a possible route from Nepal that the Khumbu Icefall was considered feasible.

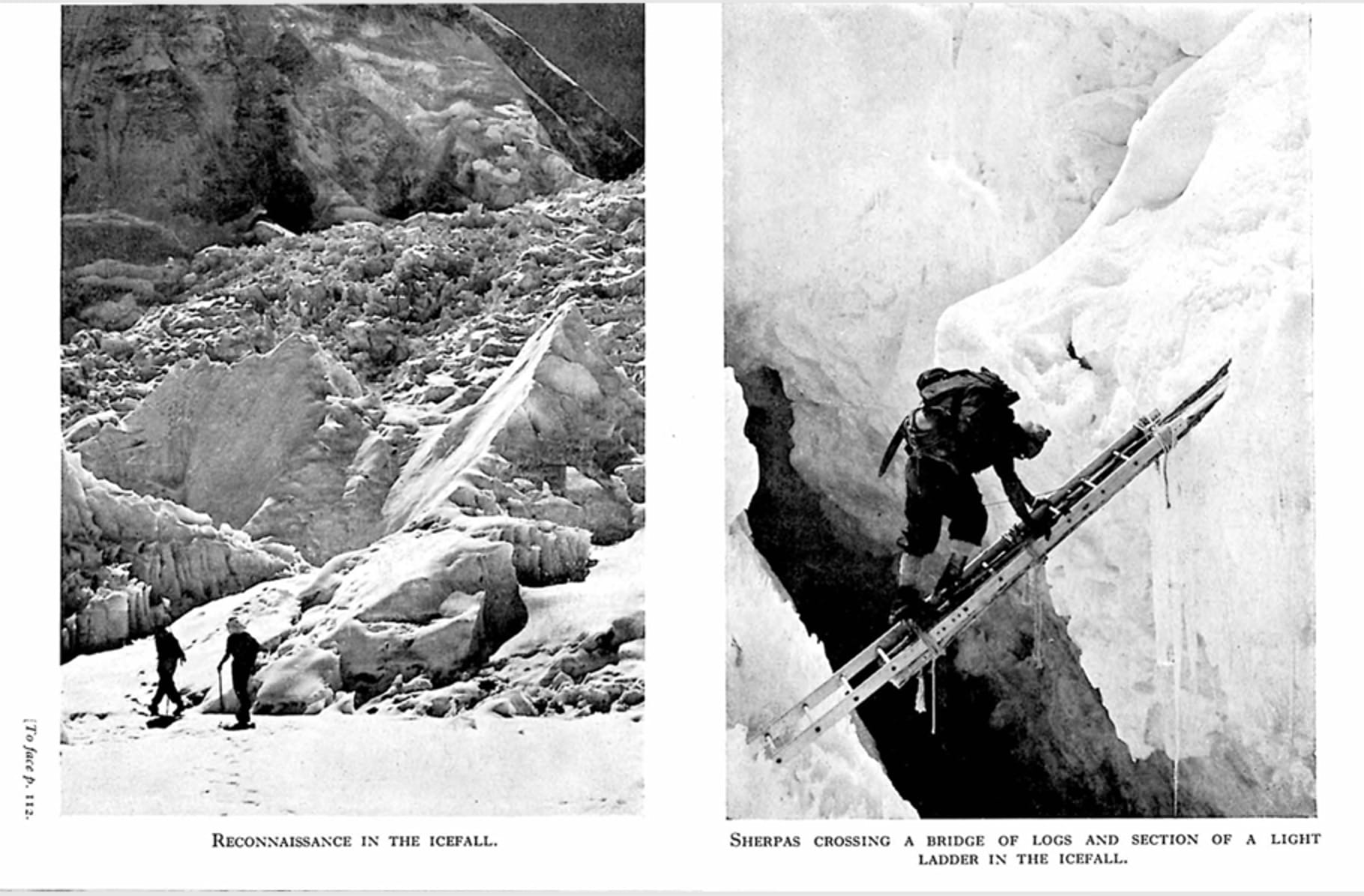

In 1951, another British team led by Eric Shipton climbed through the Icefall but stopped just short of the top due to a wide crevasse. To cross the crevasses, the early expeditions used long tree trunks brought up from the tree line after they ran out of ladders.

A Swiss team in 1952 overcame that obstacle by climbing into the crevasse and crossing a dangerous snow bridge. They reached 8500 meters using today’s Southeast Ridge route but failed to summit. Of course, John Hunt’s 1953 British expedition was the first to make the first summit using that same route.

As chronicled in the November 10, 1953, narrative of the British Everest Expedition by John Hunt and Michael Westmacott, they describe in detail climbing through Icfall and ferrying tons of loads to the upper camps in the Western Cwm. There is no mention of using a route on Nuptse or crossing the summit of Sunder Peak at 5800 meters

Is the Icefall THAT Dangerous?

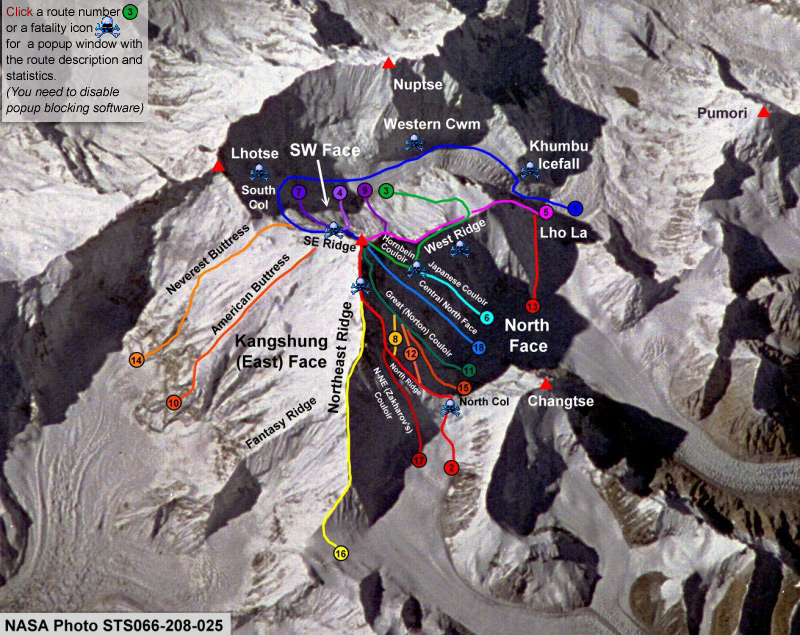

The Icefall Doctors are experts at navigating the route, but it can be challenging at times. For the first time in 2025, they used Drones extensively to scout the route and ferry ladders and gear to Camp 1. During abnormally dry winters, like 2024/25, when there are also high winds, climbers are in constant peril from dangerous rockfalls from Everest’s West Shoulder onto the Icefall. This map illustrates that various routes have emerged over the years, depending on the prevailing conditions.

The upper Icefall is a jumble of house-sized ice blocks strewn across the glacier as it descends from the Western Cwm. Gravity pulls them apart, while the friction at the base against the rocks keeps them in place. The result is enormous gaps that often require long ladders to cross.

Statistically, the Icefall is NOT most dangerous section

Contrary to popular belief and media reports, the Nepal side has more dangerous sections than the Icefall. Yes, if measured by single events, more deaths have occurred there, such as in 1970, when six Sherpas died in the Icefall, in 2014, when sixteen Sherpas died when a serac collapsed off West Shoulder, and in 2023, when three Sherpas died in the upper Icefall when it collapsed.

I used the Himalayan Database to analyze the non-illness deaths between 17,500’/5400m and 19,500’/5940m, those in the Icefall proper through 2024 (data for the 2025 season is unavailable at this time).

Of the 225 total deaths on the Nepal side, 44 or 19% occurred in the Icefall. Virtually all these deaths were Sherpas ferrying loads to camps in the Cwm and above. Of note, 57 climbers, or 25%, have died above 8400 meters, between the Balcony and the summit.

Let’s break down where and how the deaths occurred in the Icefall. While I cite specific deaths to help others, I extend my condolences to all family, friends, and teammates of these tragic events.

- 22 – Avalanche (16 in 2014 from Everest West Shoulder from the hanging seracs)

- 17 – Icefall Collapse (Similar to what we saw in spring 2023, taking three Sherpas)

- 3 – Crevasse

- 1 – Illness

- 1 – AMS

Crevasse: 6 or 13%

Falling into a crevasse is quite common on mountains from Mont Blanc to Rainer to Everest. I fell into a crevasse outside of Camp 1 in 2002! On Everest, the standard protocol is to be clipped into the fixed rope at all times while moving up or down the Icefall so that if you step on a soft snow bridge and fall into a crevasse or slip off a ladder, the rope will catch you. Sadly, many falls into crevasses were the result of not being clipped in.

In 2005, a westerner fell into a crevasse while crossing a soft snow bridge. Adventure Consultants team members who witnessed the fall all agreed: “It was clear that this climber was not clipped into the fixed ropes at the time of his fall; thus, a slip which should have been quickly arrested resulted in a fatal fall over a 10m drop.” 3

In 2012, a Sherpa fell from a ladder while not clipped into the fixed ropes and fell 150’/46m into a crevasse. 4

Icefall Collapse: 15 or 33%

The next hazard is being hit by an ice structure that collapses within the Icefall itself. There are many towering seracs (ice towers) that can fall over as the Icefall shifts, or an entire section can simply collapse under a climber – remember, it can move a meter each day and can shift suddenly with no warning. Amazingly, this event is not very common but can easily cause death.

A tragic example is from 1972, when an Australian climber supporting Chris Bonington’s British Everest SW Face Expedition was ferrying loads. He entered the Icefall but was not seen again. A search team found a large section of the Icefall that had collapsed, and assumed he was in that area when it happened. In 2008, his body was found at the foot of the Icefall. 2

Avalanche: 22 or 49%

Ice falling off the West Shoulder of Everest has resulted in massive casualties and is widely considered the most pressing danger in modern times. Two major events illustrate the danger. In 1970, six Sherpas were killed while supporting a Japanese expedition, and in 2014, on one of the worst days in Everest history, 16 Sherpas died on 18 April when a hanging serac was released as the Sherpas were waiting for a ladder to be replaced over a crevasse as they were ferrying loads to the higher camps.

In the autumn of 2019, a house-sized piece of ice barely hung about 3,000 feet above the icefall. All of the teams attempting Everest that season ended their efforts, fearing the serac would release just as they passed beneath it, as in 2014. At an unknown time, and with no witnesses, it released, leaving a debris field across the Icefall.

Who Does the Work?

The route through the Icefall to Camp 2 is put in and maintained by a small team of Sherpas aptly called the Icefall Doctors. The name was coined by New Zealand guides Rob Hall and Gary Ball, who saw how these Sherpas used ice screws and ropes to create a safe path with surgical precision.

On the south side, the Icefall Doctors, a team of eight dedicated Sherpas, install, a.k.a. “fix” the route from Everest Base Camp to Camp 2 in the Western Cwm each year. They first scout the route for the safest, most direct path; then they carry hundreds of pounds of rope, ladders, ice screws, and pickets on their backs into the Icefall and the Western Cwm to create the route.

Some years, the Nepal government allowed the ropes and anchors to be helicoptered to Camp 2, thus saving an estimated 78 Sherpa loads through the Icefall. And in 2025, drones were used extensively from EBC to Camp 1. The labor and materials are funded through climbing permits or collections from the teams.

The ropes must be reset each season because ultraviolet rays from the sun degrade them, increasing the risk of failure under the weight of a climber’s fall. In addition, the route must be maintained daily throughout the season, given that the Icefall is a moving glacier that can advance up to 3 feet a day. This movement will cause ladders to drop into crevasses, bend them, or move them into a dangerous area. The Doctors inspect the route at least once a day throughout the season to keep it open and safe.

From Camp 2 to the summit on the south side, the Expedition Operators Association (a group of guide company owners) awards the contract to set the line from Camp 2 to the summit. Recently, they have included fixing to the summit, previously done by a commercial team.

It’s a difficult and dangerous job. In 2013, Mingmar Sherpa, one of the Icefall Doctors, died after falling into a crevasse between Camps 1 and 2 in the Western Cwm.

The Traditional Route

In the past decade, it had shifted more towards the West Shoulder because the Icefall Doctors could create the route faster there. But the danger was obvious with the serac looming overhead. A decade ago, looking at old maps and pictures, longtime veterans Pete Athens and David Breashears suggested the route should return towards Nuptse, as it did in the 1950s.

Starting in 2015, the Doctors did just that, making it shorter and safer. The route was not fully tested because the earthquake ended that season early, but in 2016 and 2017, they used the same path with good results, though some sections were steep and difficult. Similarly, good results in 2018 and 2019.

Safety in the Icefall

With all of this history, how do you protect yourself while climbing in the Khumbu Icefall?

For foreigners, it may take over 6 hours to climb to Camp 1 on the first rotation. Once they are acclimatized, the time can be cut in half, but most people still take 4 to 5 hours. This means leaving base camp no later than 3:00 am. However, most teams are on the ice by 2:00 am. Sherpas will leave as early as 1:00 or 2:00 because they make a 7-hour round trip. Impressively, they take the same time for a round trip as a foreigner does one way!

Skills Review

Most teams will take a few days to review basic skills before entering the Icefall. Sherpas will set up a short course with a couple of ladders and a fixed line running over a large block of ice. While it may seem odd to others that anyone already at Everest Base Camp should practice clipping on and off a fixed rope, using a jumar, or front-pointing on steep ice with crampons, this review sharpens everyone’s skills and is a good use of time.

Safety Habits

These are the most common precautions climbers use to protect themselves:

- Never be in the Icefall when the sun is touching the ice, thus heating it up and causing movement

- Always be clipped into the fixed rope, including on ladders

- Never stop for more than a few minutes at any location in the Icefall

- Move as fast as you can safely

- Let faster climbers go by

But even these steps will not prevent something unexpected from occurring. The 2014 serac release occurred well before the sun hit the Icefall. It was around 6:45 am, and the sun usually touched the ice around 10:00 am. Also, ice screws that attach the fixed ropes to the ice will melt out, removing the safety net provided by the ropes. So the best strategy is to move fast, confident, and have extensive experience climbing in crampons on steep snow and ice – the more experience, the safer you will be.

Avoiding the Icefall

So what is a climber to do to be as safe as possible relative to the Icefall if they want to climb on the Nepal side? First, minimize your trips through the Icefall. Second, strongly support minimizing the Sherpa trips by:

- Limit the amount of luxury gear you have at Camp 1 and above. For example, on Denali, you never have tables and chairs and a vast dining tent at high camps, so why on Everest, especially with expedition length shortening each year?

- Support transporting all fixed line gear by helicopter to Camp 2, thus reducing the Sherpas’ trips carrying the loads, even if it means spending a bit more money for permits, etc.

- Minimize how much supplemental oxygen you use; go with a safe amount, but don’t overdo it by buying the “extra, unlimited bottles” offered by some guides. Each bottle is carried on a Sherpa’s back, which means extra trips through the Icefall, and if you have extra oxygen, that requires a second Sherpa to carry more bottles.

- Reduce the Sherpa support. Today, it’s common for each person to have a “Personal Sherpa,” and some members have a 2 or even 3:1 support-to-client ratio after other members drop out. Leaders should limit the number of Sherpas who are not directly supporting a member. Looking at 2025 on the Nepalese side of Everest, 517 foreign nationals were granted climbing permits. Based on my estimates and available public sources (the Nepalese government has ceased publication of statistics for unspecified reasons), the unofficial summit figures for 2025 suggest a total of 678 summits, consisting of 257 clients supported by 421 support climbers, yielding a client-to-support-climber ratio of 1:1.6. This number marks the second-highest total of summits recorded, following the 787 summits achieved in 2024.

Summary

So, is an alternative route to the Icefall a good idea? Yes, while not the MOST dangerous section, it is dangerous and carries constant risk of being at the wrong place at the wrong time, so your safety is somewhat out of your control. Is the Nuptse alternative the best one? Well, it may be the only viable option. Of course, climbers could climb the highly technical Lho La Pass to gain the West Ridge before attempting the harrowing Hornbein Couloir. But even then, most climbers would still return to EBC via the Khumbu Icefall. Note that no guide offers this as a commercial Everest route.

What about helicoptering to Camp 2, thus bypassing the Icefall completely? This has been discussed and debated for years, and the official government policy is that helicopters are to be used for medical evacuations only, not to assist tired climbers or to make the mountain “safer.” However, each year we are seeing more climbers (with their guides’ support) ignore the rule and fly in and out of Camp 2 to avoid the Icefall, or due to fatigue.

So that leaves us with the option of forgetting about climbing from the Nepal side, with its crowds and hazards, and instead climbing from the less crowded, arguably safer Tibet side. There was a historical precedent for this side being less expensive; however, today, the costs are similar. When comparing the technical difficulty of the two sides, the North is more difficult, primarily because there is less snow, so you climb on rocks with your crampons, which is significantly more demanding. However, the Tibetan side is windier, dustier, and colder, and as of now, the Chinese ban all helicopter rescues, so if you get in trouble, you are dependent on those around you to help. But there is no 2,000-foot Khumbu Icefall to deal with.

Bottom line: if you prefer the Nepal side for the aesthetics, trek through the Khumbu to base camp, interacting with more local people and enjoying the hospitality of the teahouse staff and the mystic of the monasteries, the best way to manage your Icefall time is to pre-acclimatize at home by following a multi-week, structured program of sleep and training in a simulated high-altitude environment, typically recommended for at least 12 weeks and involving 400+ hours of exposure. This Alpenglow training document shows how to train with a tent. This will get you to 17,000 feet (some say up to 23,000). When combined with an acclimatization climb of a nearby trekking peak such as Lobuche, Island (Imja Tse), or Mera, Everest can be climbed with only one or two rotations, reducing your one-way trips through the Icefall to two or four.

OK, so no matter which side you climb, train hard and be prepared physically, emotionally, and mentally.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

references

- https://glacierchange.wordpress.com/2009/12/09/khumbu-glacier-decay/

- http://www.frof.ch/absent-friends/tony-tighe/

- http://www.mounteverest.net/story/EverestshowsitsdarkestfaceTwodeathsinthreedaysMay32005.shtml

- http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/everest/blog/2012-04-21/tragedy-on-the-mountain?source=news_sherpa_fall

- https://books.google.com/books?id=Td0rVmVnkR8C&pg=PT49&lpg=PT49&dq=terribly+steep+and+broken+george+mallory&source=bl&ots=SYBw3DVWEU&sig=tGcuWRnMqpxDyxCAGom55ntaKJk&hl=en&sa=X&ei=aCrkVLvfOonXggSG1ICYAQ&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=terribly%20steep%20and%20broken%20george%20mallory&f=false

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2025 podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Breaker, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

9 thoughts on “Everest 2026: Khumbu Icefall Bypass-Real or a Dream?”

Hiya Alan, hope you and your family are doing well, been a while since we’ve spoken, I thought this topic coming up was rather strange as I thought it was talked about after the 2014 release/avalanche and the idea was vito’d then, surprised that it’s actually coming up again, guessing it’s just a pipe dream to make it safe,

But anything to make the Sherpas working environment safer would be a good thing,

You still chat with kami? Is he doing ok?

Hi John, always nice to hear from you. Yes, as I say in the post, it’s not a new idea and infact close to 15 years old and most likely decades before that. I’m sure they will get it in, I’m just unsure if it will achieve the commercial success they want. Yes, still in touch with Kami and his familiy. Thye are well, but Kami is slowing down on his guiding as he’s approaching 60ish.

Just approaching 60! So just getting started, he’d be allowed to accompany proper climbers soon then ,

Seriously tho, that’s a great achievement still being a superman at that age,

Its people like kami that are the ones that should be making the rules to make these places safer, as there’s so much knowledge they have amassed over the years, especially guiding less accomplished climbers,

But good it’s all ok with you and yours and kami and his

Great article! Thanks. Pattie

Thanks Pattie!

As usual- comprehensive and well documented!

Appreciate this Robert. I try.

Interesting read, in a few year’s time we will find out if the new via ferrata gets any use actually.

One point about the route the early expeditions used: 1952 Swiss and 1953 Hunt expeditions walked in all the way from Kathmandu Valley, not just from Jiri. The road to Jiri was not finished until 1985! I also suspect that those early expeditions did not go through Jiri at all, as the main trade route from Kathmandu to Khumbu went via villages of Yersa and Those further south, after all Jiri was not a bazaar town the road turned it into, but just a hamlet like any other during those early times. It is not mentioned in any Hunt expedition documents that I have seen. “Follow the footsteps of Hillary” is just half-true marketing speak, no trekking agency arranges treks starting from Bhaktapur or Banepa in the Kathmandu Valley where the porters and members of the expedition started their 17 day walk to Tengboche.

Thanks for the additional details! The reason I mentioned Jiri is that several Kathmandu based giide companies are now marketing the trek from Jiri to Luka as an alternative to flying.