Welcome to my ongoing Everest 2026 coverage! 2026 marks my 23rd year covering all things Everest. If you’re a long-time reader, welcome back. If you’re new here, thanks for joining me. Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2026 Edition is an exhaustive review of the climbing routes related to Everest mountaineering.

I rely heavily on data from the Himalayan Database (HDB) for summit and death statistics. The HDB—free to download—documents climbs on Nepalese and Tibetan peaks (excluding Pakistan), dating back to 1905.

I use their terms for climbers and guides. For example, “hired” refers to support staff, including Sherpas and other ethnic groups such as Tamang, Magar, and Rai; on the north side, Chinese and Tibetan workers fill similar roles. “Member” typically refers to a climber who pays for guided support. I use “members,” “foreigners,” and “Westerners” interchangeably, though some climbers—such as those from South Korea—do not consider themselves Western. I define an attempt as a climber leaving base camp with the intention to summit.

This post complements the following articles as we near the start of the season in April.

- Welcome to Everest 2026 Coverage – An overview of what to expect during the Spring 2026 climbing season

- Everest by the Numbers: 2026 Edition – A deep dive into Everest statistics as compiled by the Himalayan Database

- Comparing the Routes of Everest: 2026 Edition – A detailed look at Everest’s routes, commercial, standard, and non-standard

- How Much Does it Cost to Climb Everest: 2026 Edition – My annual analysis of Everest climbing costs, from solo and unsupported to fully guided

You can sign up for (or cancel) email notifications in the lower-right sidebar, or simply check the site regularly.

Why This Coverage?

I have one reason for this coverage: Alzheimer’s. I lost my mom, Ida, and four aunts to the disease, which has changed my life. Please read more at this link. I hope you find value in my coverage and consider donating to select nonprofits or any organization of your choice. I receive no financial benefit from your donations. Click the button on the right sidebar to donate.

Bottom Line

For 98% of all Everest climbers, the choice of routes is either the Northeast (Tibet) or Southeast (Nepal) Ridge. For today’s commercial clients, all other routes are too dangerous, too complex, and not commercially viable. This post will examine the various routes and explore the most popular commercial ones. It may be an exaggeration to say that all the routes on Everest have been climbed, since the next generation of climbers continues to blaze new trails. However, climbing Everest appears well understood across all aspects of the hill. There are about twenty named routes, almost all of which have been tried at least once, with teams summiting. Many sections and parts of well-known routes still have not been climbed, and some Faces have not been climbed in a direct line, aka direttissima.

Opportunities do exist for a new route or line on Everest, and I’m eager to see someone break the commercial stranglehold.

Preparing for Everest is More than Training

Dreaming of climbing a Colorado 14er, Mount Everest, or K2? With 30 years of high-altitude climbing experience, Alan Arnette and Summit Coach provide personalized plans to help you achieve your goals. Visit the Summit Coach website for pricing and services.

2025 Review

Strong winds, drones, demanding climbing, and increasingly sophisticated logistics defined the 2025 Everest spring season. Frostbite cases and helicopter evacuations were common, though many incidents likely went unreported. Once again, Everest reminded climbers that at 8,848 meters, preparation is non-negotiable.

According to the Himalayan Database’s December 2025 update, 851 climbers reached the summit during the spring season — 731 from Nepal and 120 from Tibet — making 2025 the third-busiest Everest season on record, behind only 2019.

On the South side, 303 members were supported by 428 Sherpas, a 1.4:1 support ratio reflecting the growing need for assistance among less-experienced climbers. The North side saw 68 members and 52 Sherpas, a 0.76:1 ratio, consistent with its appeal to more seasoned alpinists.

Men accounted for 766 summits (56% success rate), while 85 women reached the top with a notably higher 76% success rate, continuing a strong upward trend in women’s participation and performance. Nearly every climber used supplemental oxygen—only four did not—underscoring its central role in modern Everest support.

Route Performance

Some of the best mountaineering guides had stellar days, proving that Everest can be climbed without crowds or drama. On the South side, 63% of members with permits (303 of 481) summited. Madison Mountaineering summarized their summit experience:

“Our Mount Everest team just returned to Kathmandu after a successful summit on May 23rd. They enjoyed a perfect summit day with no crowds—a rare gift on the world’s highest peak—and had the top of the world entirely to themselves!”

The North side posted a much higher rate of 86% (68 of 79). Alpenglow noted:

“This spring, our Alpenglow Expeditions team returned to the North Side of Mount Everest with a small crew and a big plan. After months of preparation, pre-acclimatization, and weather watching, our Everest expedition 2025 culminated in an incredibly rare summit day—blue skies, no wind, and a quiet mountain.”

Continue reading about Everest 2024

2026 Preview

For spring 2026, I expect 900 to 1,000 total summits from both sides combined, exceeding the previous high-water mark set in 2019, when 877 climbers summited (661 from Nepal, 216 from Tibet. A realistic breakdown for 2026 would include at least 225 summits on the Tibet side (members and hired combined) and well over 800 from Nepal, compared to 731 from Nepal and 120 from Tibet in 2025.

Nepal

Operationally, expect continued drone use, particularly in the Khumbu Icefall, to support the Icefall Doctors by ferrying ropes, ladders, and equipment across the Icefall, reducing the number of heavy-load carries and lowering Sherpas’ exposure to falling or collapsing ice structures. Drones are also expected to play a larger role in removing waste from high camps, helping clean the mountain without adding to Sherpa workloads.

Over the past year, Nepal has announced several new rules in the Tourism Bill 2081, which have not yet been approved. You can follow its current status at this link, which is listed as “Discussion in Committee” as of January 2026.

Among the new rules from Nepal is a proposal to eliminate the $4,000 refundable trash deposit per expedition and replace it with a nonrefundable $4,000 fee per climber to fund a Sherpa-staffed checkpoint at Camp 2 that will monitor that climbers bring down what they’ve brought up. It’s unclear how operators will manage this new fee when or if it goes into effect, i.e., absorb it or pass all or part of it on to members.

Nepal’s decision, implemented in September 2025 to raise the Everest climbing permit for foreign climbers from $11,000 to $15,000, is unlikely to significantly reduce overall demand. Price competition among lower-cost Nepalese operators remains intense, while demand for premium, fully guided expeditions led by foreign operators continues to grow. However, the higher permit fee may push a modest number of climbers toward the Tibetan side, particularly those seeking fewer crowds and a more controlled climbing environment. Note that this permit increase is in addition to the proposed $4,000 trash fee.

Beyond the previously mentioned changes, there is widespread confusion about a set of new rules proposed by the Nepal Ministry of Tourism, as I described in a post last year. The most significant change is that all Everest permit applicants must have climbed a 7000-meter peak in Nepal. Note that Aconcagua or Denali would not qualify you to climb Everest.

Tibet

China has returned to normal operations after a few years disrupted by the pandemic. From 2019 to 2022, only Chinese scientists and technicians were allowed to climb, and they installed and maintained a weather station near the summit.

Unlike Nepal, which has no limit on the number of permits issued for Everest, China has a maximum of 300 annual permits for hired and member teams. The only time there were more summits than 300 was in 2007, when 197 members, supported by 178 hired, reached the top, totaling 375. Since 2010, the median has been well under the quota of 153 people, so this should not be an issue in 2026. However, we may see North Side crowds increase in 2026 as Nepal’s price increases for the Everest take effect.

Only a few Western companies, including Alpenglow Expeditions, Furtenbach Adventures, Kobler & Partner, and Summit Climb, regularly, but not always, guide on the Tibetan side. Most established Nepalese and Tibetan operators run expeditions, such as Lhasa-based Yala Xiangbo Mountaineering Adventure Co., Climbalaya, and Seven Summits Treks.

There are a few new rules for this season, but, as usual, China does not publish them publicly; it announces them only to selected operators. For example, last year they announced that all climbers must use supplemental oxygen on all three of their 8000-meter peaks, but not every operator received that guidance. They also announced that, for 2026, all Everest climbers must have climbed a 7,000-meter peak. It’s unclear whether any of these requirements are enforced; for example, last year several climbers summited 8000ers in Tibet without supplemental oxygen.

Who’s Climbing

As in the pre-pandemic years, expect more climbers from China, India, and Southeast Asia than ever. As I’ve detailed, China requires all Chinese Nationals to climb an 8000-meter peak before climbing Everest from China; thus, many go to Nepal, where there are no experience requirements. The Chinese have added a 7,000-meter requirement for all non-Chinese climbers. As for the Indian climbers, it’s folklore that if you summit Everest, you can leverage that into fame and fortune – a considerable miscalculation by many. However, many Nepalese/Indian guide companies meet this market demand, create profitable businesses, run training programs for the under-20 crowd, and then take them to Everest. Unfortunately, this approach is a high-risk gamble that may backfire.

Follow the 2026 Everest Coverage!

Routes

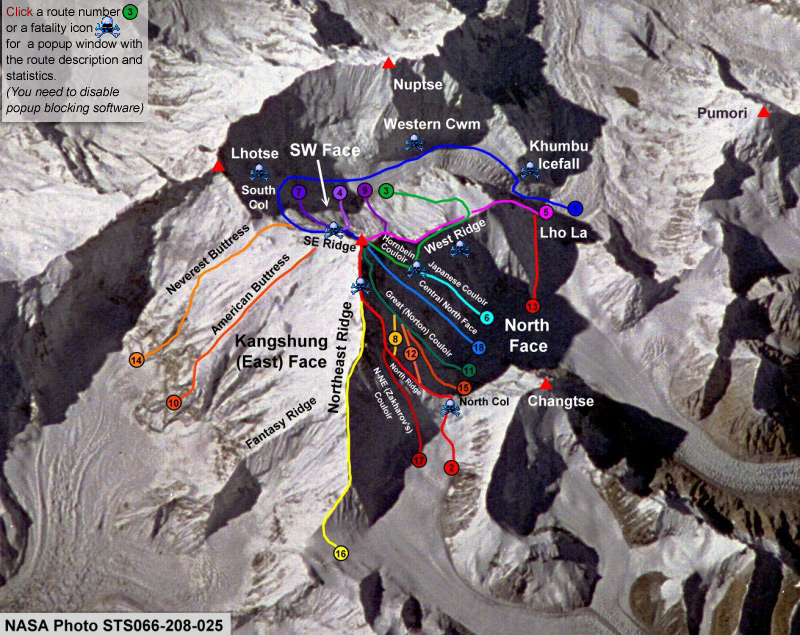

It is challenging to analyze the routes because they are often named after their geological features, the national team, or even the person who first climbed them. However, about 20 climbing routes have been identified on Mt. Everest. Everest has three faces: the Southwest Face from Nepal, the East Face (aka Kangshung Face) from Tibet, and the North Face, also from Tibet. The Kangshung Face has seen the fewest attempts and even fewer summits.

Standard-98% vs. Non-Standard Routes-2%

One of Everest’s lesser-known statistics highlights just how dominant the standard routes have become. As of December 2025, of the 13,737 total summits, only 187 ascents (141 members and 46 hired climbers) reached the summit via non-standard routes — meaning routes other than the Southeast Ridge or Northeast Ridge. That represents just 1.4% of all summits.

The non-standard routes have many variations. For example, you can climb the standard Northeast Ridge to the summit and return via the Great Couloir or the North Face. The Southwest Face is also popular; this variation includes the Bonington Route and climbing via the Rib. While most climbers on the north side take the Northeast Ridge route, they join the ridge in the middle. A Japanese team made the first ascent of the true Northeast Ridge in 1995. One section of that route, called the Pinnacles, is highly technical and challenging. Navigating this section took them three days and 1,250 meters of rope.

The countries with the most summits on the non-standard routes are Nepal (67), Japan (26), the USA (27), S. Korea (23), the USSR (23), and Russia (16).

Using the Himalayan database, I researched non-standard routes to estimate their volume. This is not an all-inclusive list.

| ROUTE | SUMMITS | DEATHS | LAST ATTEMPT |

| Khumbutse-W Ridge-N Face (Hornbein Couloir) | 2 | 1 | 1989 |

| Lho La-W Ridge | 19 | 2 | 1989 |

| N Face | 24 | 0 | 2004 |

| S Pillar | 45 | 1 | 2000 |

| SW Face, including the Bonington Route | 48 | 2 | 2009 |

| West Ridge- North Face- Hornbein Couloir | 8 | 0 | 1986 |

| E Face | 12 | 0 | 1999 |

The Deadly Route?

These non-standard climbs accounted for 70 deaths (44 members and 26 hired), representing 21% of all Everest fatalities, despite comprising only 2% of total ascents. In contrast, 78% of all Everest deaths occurred on the standard routes, and the Southeast Ridge alone accounts for 57% of total deaths. This disproportionate risk helps explain why nearly all commercial operators concentrate on the standard routes, where hazards are better understood, infrastructure is fixed, and rescue access is possible.

Here is the death summary through 2025:

Reason | Northeast Ridge | Southeast Ridge | Other Routes South | Other Routes North | Total |

Avalanche | 9 | 41 | 13 | 14 | 79 |

Fall | 18 | 34 | 18 | 8 | 78 |

AMS | 12 | 31 | 0 | 5 | 48 |

Exposure/Frostbite | 11 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 26 |

Illness (non-AMS) | 5 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 27 |

Exhaustion | 12 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 32 |

Icefall Collapse | 0 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 19 |

Crevasse | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

Disappearance | 4 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 13 |

other/unknown | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

Falling Rock/Ice | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

Total | 74 | 195 | 34 | 36 | 339 |

Death Rate for those above BC | 0.89 | 0.98 | 2.28 | 1.83 | |

% of Total | 21% | 57% | 11% | 12% |

The End of New Routes?

The last successful new route on Everest was completed in 2009, when a Korean team climbed the Southwest Face. Since then, attempts have been rare.

In 2019, Cory Richards and Esteban “Topo” Mena made a bold attempt on a 6,551-foot direct couloir line on Everest’s Northeast Face from the Tibet side. Starting above Advanced Base Camp (21,325 ft), the line joined a high ridge before continuing up steep terrain toward the summit. After 40 hours on the wall, including an open bivouac, the pair turned back at roughly 7,600 meters, citing deteriorating conditions, accumulated fatigue, and tactical limitations.

“Unclimbed” Routes

Many sections of Everest have not been climbed, and some Faces have not been climbed in a direct line, aka direttissima. It can be argued that the complete route has not been climbed when combining different routes. This example applies all over Everest. However, there are some clear (I think) examples like the Southwest Face Direct, North Face Direct, and East Face (Kangshung) Direct. One route remains unclimbed: the East Ridge, also known as Fantasy Ridge. This extremely dangerous, avalanche-prone area has been deemed unclimbable in years with little snowfall, as Dave Watson and the team on the Fantasy Ridge showed in 2006.

New Routes

The last team to complete a new route was a Korean team on the Southwest Face in 2009. In 2019, Cory Richards and Esteban “Topo” Mena made a valiant attempt to send a 6,551-foot direct line in a couloir, a narrow rock gully, on the Northeast face of Everest. The gully joins a high ridge, continues to a steep face, and on to the summit. The route began just above Advanced Base Camp at 21,325 feet on the Tibet side of Everest. Eventually, they turned back at around 7,600 meters due to “conditions we encountered coupled with our chosen tactics compounded by exertion.” They had spent 40 hours on the wall with one open bivvy.

Everest Faces

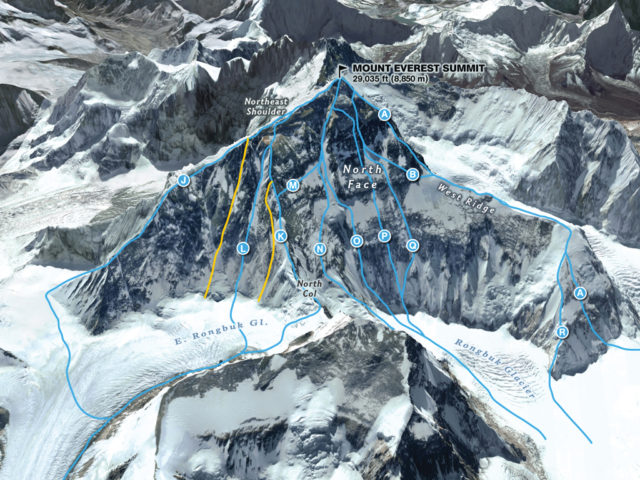

This is a list by Face with descriptions that include the common names plus some used by the Himalayan Database. The illustrations are courtesy of National Geographic (Martin Gamache, Jaime Hritsik, Chiqui Esteban, Ng Staff Sources: 3D Reality Maps; The American Alpine Journal; The Himalayan Database; Ed Webster; East Face Imagery Courtesy Of Digital Globe @ 2012; Raphael Slawinski). National Geographic published a great 2015 piece on a proposed new route, with excellent articles and animations, but it has since taken it down.

North Face

- (J) Integral N.E. Ridge – 1995 Japanese team

- (L) Russian Couloir – 2004 Russian

- (K) The Complete NE Ridge, N-NE

- (M) South Pillar, NE Ridge-N Face-Norton Couloir I – Messner Solo Route 1980 Messner Italian

- (N) American Direct – 1984 American

- (O) The Great Couloir aka Norton Couloir (White Limbo) – 1984 Australian

- (P) Russian Direct – 2004 Russian

- (Q) Japanese Supercouloir – 1980 Japanese

- (A) West Ridge Direct – 1979 Yugoslavian

- (R) Canadian Variation – 1986 Canadian

East Face

Southwest Face

Standard Routes

By now, you know two routes dominate Everest, with 12,697 out of the 13,737 summits following the same basic route pioneered in 1953. John Hunt’s British expedition to the summit used the Southeast Ridge-South Col, and Shi Zhang’s 1960 summit attempt used the Northeast Ridge-North Col. Today, these routes seem to be caught up in guide politics over which is safer, the degree of difficulty, and the likelihood of success. Either side can make an argument for climbing.

Southeast Ridge – South Col Route

| Pluses | Concerns |

| Beautiful trek to base camp in the Khumbu | Khumbu Icefall instability |

| Easy access to villages for pre-summit recovery | Crowds, especially on summit night |

| Helicopter rescue from as high as Camp 3 at 23,500’–if necessary | Cornice Traverse exposure and Hillary Step cornice instability |

| Slightly warmer sometimes, with lower winds | Slightly longer summit night |

Northeast Ridge – North Col Route

| Pluses | Concerns |

| Fewer people (half of the Nepal side) | Colder temps and harsher winds |

| Can drive to base camp | Camps at higher elevations |

| Easier climbing to mid-level camps | More difficult with smooth or loose rocks |

| Slightly shorter summit night | Currently, there is no opportunity for helicopter rescue at any point |

Now, let’s take an in-depth look at both sides.

South Col/Southeast Ridge Route

Mt. Everest was first summited by Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and New Zealander Edmund Hillary with a British expedition in 1953. They used the South Col route, which had only been attempted twice by Swiss teams in the spring and autumn of 1952. They reached 8,500 m, well above the South Col. Norgay was with the Swiss, gaining the experience he would use on the British expedition. The Swiss returned in 1956 to make the second summit of Everest.

This is a typical south-side climb schedule showing the average time and the distance from the previous camp, plus a brief description of each section. Of course, this schedule is subject to change. Some operators running “speed” climbs will skip some of these steps. More details can be found on the South Col route page.

- Acclimatization at home using a Hypoxic Altitude Tent

- Many climbers use altitude tents to acclimatize at heights between 17,000 and 23,000 feet (5181 -7000m) in their homes before arriving in BC. This reduces the expedition to a couple of weeks and eliminates most, if not all, rotations.

- Trekking Peak Acclimatization: Lobuche 20,161′

- Many teams now summit a trekking peak to acclimatize, reducing the need for a single trip through the Icefall.

- Basecamp: 17,500’/5334m

- This is your home away from home. Located on a moving glacier, tents can shift, and platforms melt. The area is harsh but beautiful, surrounded by Pumori and the Khumbu Icefall with warm mornings and afternoon snow squalls. With so many expedition tents, pathways and generators, it feels like a small village. Today, constant helicopter and drone flights dominate the otherwise quiet environment.

- C1: 19,500’/5943m – 4-6 hours, 1.62 miles

- Reaching C1 can be a dangerous part of a south climb since it crosses the Khumbu Icefall. The Icefall is 2,000′ of moving ice, sometimes as much as 3 feet (1 meter) a day along the edges. But it is the deep crevasses, towering ice seracs and avalanches off Everest’s West shoulder that create the most danger. However, more climbers die on other sections of Everest than in the Icefall.

- C2: 21,000’/6400m – 2-3 hours, 1.74 miles

- The trek from C1 to C2 crosses the Western Cwm and can be hazardous due to crevasse risk. However, the extreme heat takes a toll on climbers. Again, avalanche danger exists from Everest’s West Shoulder and the northern flanks of Nuptse, which has dusted C1.

- C3: 23,500’/7162m – 3-6 hours, 1.64 miles

- Climbing the Lhotse Face to C3 is often challenging because most climbers experience the effects of high altitude and are not yet using supplemental oxygen; however, many teams now use supplemental oxygen from Camp 2. The Lhotse Face is steep, and the ice is hard. The route is fixed with a rope. The angles can range from 20 to 45 degrees, up to 65 degrees, slightly above the highest C3. It is a long climb to C3, and these days, few teams require it for acclimatization before a summit bid.

- Yellow Band – 3 hours

- The route to the South Col begins at C3 and crosses the Yellow Band. It starts steep but levels off as altitude increases. Climbers are usually in their down suits, and some are using supplemental oxygen for the first time. Given the altitude, the Yellow Band’s limestone rock is not complex to climb but can be challenging. Bottlenecks can occur on the Yellow Band.

- Geneva Spur – 2 hours

- This section can surprise some climbers. The top of the Spur leading onto the South Col has some of the steepest climbing thus far. It is easier to climb when there is a good layer of snow than on loose rocks.

- South Col: 26,300’/8016m – 1 hour or less

- Welcome to the moon. This flat area is a saddle of loose rock, surrounded by Everest to the north and Lhotse to the south. Generally, teams anchor tents with nets or heavy rocks to withstand hurricane-force winds. This is the staging area for the summit bids and the high point for Sherpas to ferry oxygen and gear for the summit bid. Climbers not using supplemental oxygen will usually tag or even sleep at the Col and return to EBC before making their summit bid. Today, there’s a lot of human feces and trash need to be removed.

- Balcony: 27,500’/8400m- 4 – 5 hours

- Officially now climbing Everest, climbers use supplemental oxygen to climb the steep, sustained route up the Triangular Face. The route is fixed with rope, and climbers create a long conga line of headlamps in the dark. The pace is maddeningly slow, with periods of inactivity, as climbers above take a break to consider whether to turn back or continue to the Balcony. It’s usually snow-covered, but there may be some exposed rock, depending on the year. Rockfall can be deadly, and almost all climbers now wear helmets. Sherpas will swap oxygen bottles for members at the Balcony while taking a short break for food and water.

- South Summit: 28500’/8690m – 3 to 5 hours

- The climb from the Balcony to the South Summit is steep and continuous. Given the terrain and altitude in this section, this is the most technical and physical section on the Southeast Ridge. While mainly climbing on a worn boot path in the snow, smooth rock slabs can be exposed in low-snow years. The climbing becomes more challenging as the angle dramatically steepens near the South Summit. Midway up the Ridge, the westerly winds are no longer blocked by Everest proper, causing many climbers to consider whether they should turn back. At this point, the views of Lhotse and the sun rising to the east are indescribable.

- Cornice Traverse and Hillary Step – 1 hour or less

- After a short downclimb from the South Summit, you encounter one of the most exposed sections of a south-side climb, crossing the cornice traverse between the South Summit and the Hillary Step. But the route is fixed and wide enough that climbers rarely have issues. The 2015 earthquake changed the Hillary Step. Climbers now report a large snow-bulb area with no rock climbing as in the past. However, in 2024, a cornice at the Step collapsed, killing two people, so speed is necessary in this area, and overcrowding must be avoided. The current ‘Hillary Slope” is still a source of bottlenecks.

- Summit: 29,035’/8850m – 1 hour or less

- The last section from the Hillary Step to the summit is a moderate snow slope with several small “false summits.” While tired, the climber’s adrenaline keeps them going.

- Return to South Col: 4 -7 hours

- Care must be taken to avoid a misplaced Step down climbing the Hillary Step, the Cornice Traverse or the slabs below the South Summit. Also, diligent monitoring of oxygen levels and supply is critical to ensure the oxygen reaches the South Col.

- Return to C2: 3 hours

- Usually, climbers are pretty tired but happy to return to higher natural oxygen levels, regardless of their summit performance. It can be very hot since most climbers still wear their down suits, and on a clear day, the sun’s unfiltered rays are harsh.

- Return to base camp: 4 hours

- The packs are heavy since everything they hauled up over the preceding month must be taken back down. It is now almost June, so the temperatures are warmer, making the snow mushy and increasing the difficulty. But each Step brings them closer to base camp comforts and on to their homes and families.

Icefall Bypass?

70-year-old French alpinist Marc Batard, twice, in 2021 and 2022, with a team of four French climbers and two Sherpas, attempted to establish a route to bypass the Khumbu Icefall by climbing on the flanks of Nuptse. He’s currently raising money for another attempt in 2026. He hopes to finish the route through what he calls “the traverse” to the Western Cwm and Camp 1 this spring. Nuptse is the southern wall above the Icefall.

The Nuptse alternative was established by Russian climbers Chochia and Shamalo in 2011, and the Soviet climber Bozhukov had proposed it several years earlier. See this excellent blog post for details and images. In 2013, Russians Urubko and Bolotov attempted to repeat it, but the attempt ended with the death of Bolotov when a rope broke while he was rappelling off the ridge and into the Western Cwm. This is another great blog post with details and images.

The Benegas Brothers advocated for this for many years, but could never make it a reality due to the objective dangers and climbing difficulty. I believe the hope of climbing Nuptse’s flanks to bypass the Icefall is over, as the route is too difficult to be used commercially.

So, is an alternative route to the Icefall a good idea? Yes, while not the most dangerous section, it is dangerous and carries a constant risk of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, so your safety is somewhat out of your control. Is the Nuptse alternative the best one? Well, it may be the only viable option. Of course, climbers could climb the highly technical Lho La Pass to gain the West Ridge before attempting the harrowing Hornbein Couloir. But even then, most climbers would still return to EBC via the Khumbu Icefall. Note that no guide offers this as a commercial Everest route.

See this 2026 post I made discussing this option in detail

Northeast Ridge Route

Everest’s north side is steeped in history, with multiple attempts throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The first attempt was by a British team in 1921. British George Mallory led a small team to be the first humans to set foot on the mountain’s flanks by climbing up to the North Col (7003m). The second expedition, in 1922, reached 27,300 feet before turning back and was the first team to use supplemental oxygen. It was also on this expedition that the first deaths were reported when an avalanche killed seven Sherpas.

The 1924 British expedition with George Mallory and Andrew “Sandy” Irvine is most notable for the mystery of whether they summited or not. If they did summit, that would precede Tenzing and Hillary by 29 years. Mallory’s body was found in 1999, but there was no proof that he died going up or coming down. Irvine’s booted foot was found in 2024, but the Kodak camera, which may hold the answer to their summit, has never been found. There is speculation that the Chinese found the infamous Kodak camera and didn’t tell the world to maintain their first summit on the Tibet side. A Chinese team made the first summit from Tibet on May 25, 1960. Nawang Gombu (Tibetan) and Chinese Chu Yin-Hau and Wang Fu-zhou, who is said to have climbed the Second Step in his sock feet, claimed the honor.

In 1975, on a successful summit expedition, the Chinese installed the ladder on the Second Step, a near-vertical rock wall of 130 feet (40m) at 28,250 feet (8,610m) and replaced it with a new one in 2007. Tibet was closed to foreigners from 1950 to 1980, preventing further attempts until a Japanese team summited in 1980 via the Hornbein Couloir on the North Face. The north side began attracting more climbers in the mid-1990s, but today it sees half the traffic of the Nepal side due to China limiting permits to 300 and unpredictable mountain closures. In 2008 and 2009, obtaining a permit was difficult due to the Beijing Olympics, thus preventing many expeditions from attempting any route from Tibet. It was closed to foreign nationals from 2020 through 2023 due to COVID-19 and bureaucratic delays.

Now, let’s look at the typical north-side schedule, which shows the average time from the previous camp, plus a brief description of each section. Of course, this schedule is subject to change. Some operators running “speed” climbs will skip some of these steps. More details can be found on the Northeast Ridge route page.

- Acclimatization at home using a Hypoxic Altitude Tent

- Many climbers use altitude tents to acclimatize at heights of up to 23,000 feet in their homes before arriving in BC. This reduces the expedition to a couple of weeks and eliminates most, if not all, rotations.

- Basecamp: 17000′ – 5182m

- It is located on a highly windy gravel area near the Rongbuk Monastery. This is the end of the road. All vehicle-assisted evacuations start here. As of 2026, there are no helicopter rescues or evacuations on the north side or for any mountain in Tibet, but this may begin in 2027 or 2028, as a tourist center has been built nearby.

- Interim camp: 20300’/6187m – 5 to 6 hours (first time)

- Used on the first trek to ABC during acclimatization, this spot has a few tents. Usually, this area is lightly snow-covered or just rocks.

- Advanced base camp: 21300’/6492m – 6 hours (first time)

- Many teams use ABC as their primary camp, not base camp, during acclimatization, but it is at a high elevation. Yaks can ferry gear from BC to ABC. This area can still be snow-free but offers a stunning view directly of the North Col. It is a harsh environment and a long walk back to the relative comfort of base camp or Tibetan villages.

- North Col or C1: 23,000’/7000m – 4 to 6 hours (first time)

- Leaving Camp 1, climbers reach the East Rongbuk Glacier and put on their crampons for the first time. After a short walk, they clip into the fixed line and perhaps cross a couple of ladders over deep glacier crevasses. The climb from ABC to the North Col steadily gains altitude, with a steep 60-degree section that will feel vertical. Climbers may use their ascenders on the fixed rope. Rappelling or arm-wrap techniques are used to descend this steep section. Teams will spend several nights at the Col during the expedition.

- Camp 2: 24,750’/7500m – 5 hours

- It’s mostly a steep, snowy ridge climb that turns to rock. High winds can sometimes make the climb cold. Some teams use C2 as their highest camp for acclimatization purposes. Climbers not using supplemental oxygen will usually tag or even sleep at C2 and return to ABC or even base camp before making their summit bid. Today, there’s a lot of human feces and trash need to be removed.

- Camp 3: 27,390’/8300m – 4 to 6 hours

- Teams place Camp 3 at several spots on the steep, rocky, exposed ridge. Now, using supplemental oxygen, tents are perched on rock ledges and are often pummeled by strong winds. This altitude and weather exposure are higher than those at the South Col. It is the launch point for the summit bid. Today, a large amount of human feces and waste needs to be removed.

- Yellow Band

- Leaving C3, climbers follow the fixed rope through a snow-filled gully in the Yellow Band. They then take a small ramp to the northeast ridge proper.

- First Step: 27890’/8500m

- The first of three rock features. The route tends to cross to the right of the high point, but some climbers may rate it as steep and challenging. This one requires good footwork and steady use of the fixed rope in the final gully to the ridge.

- Mushroom Rock -28047’/8549m – 2 hours from C3

- A rock feature that spotters and climbers can use to measure their progress on summit night. Oxygen is swapped at this point. The route can be covered with loose rock here, adding to the difficulty with crampons. Climbers will use all their mountaineering skills.

- Second Step: 28140’/8577m – 1 hour or less

- This is the crux of the Chinese Ladder climb. Climbers must ascend about 10 feet of rock slab before climbing the near-vertical 30-foot ladder. This section is very exposed, with a 10,000-foot vertical drop. The descent is more challenging to navigate because you cannot see your feet on the ladder rungs while wearing an oxygen mask and goggles. This brief section is notorious for long delays, which increase the risk of frostbite or AMS.

- Third Step: 28500’/8690m – 1 to 2 hours

- It is the easiest of the three steps, being 30 feet (10m), but it requires concentration to be safe.

- Summit Pyramid – 2 to 4 hours

- At this point, climbers feel very exposed on a steep snow slope that is often windy and brutally cold. Towards the top of the Pyramid, climbers are extremely exposed again as they navigate a large outcropping and experience three more small rock steps on a ramp before the final ridge climb to the summit.

- Summit: 29,035’/8850m – 1 hour

- The final 500′ horizontal distance along the ridge to the summit is entirely exposed. Slope angles range from 30 to 60 degrees.

- Return to Camp 3: – 7 -8 hours

- The downclimb takes the identical route. Early summiteers may experience delays at the Second Step, with climbers going up or summiteers having downclimbing issues.

- Return to ABC: 3 hours

- The packs can be heavy since everything hauled up over the preceding month must be taken back down. As it is now almost June, temperatures are warmer, making the snow mushy and increasing difficulty. However, each Step brings them closer to base camp comforts and to their homes and families.

For a more detailed description and route pictures, please take a look at the Northeast Ridge route page.

Summary

I am often asked which side or route is safer, and my answer is: pick your poison. However, the standard routes are the safest. The non-standard routes are the domain of elite and highly skilled alpinists, and even with their talent, the death rates soar. The south has the Khumbu Icefall on the standard routes, while the north has the Steps and Weather. However, these numbers clearly show that the South has a higher death rate.

Despite the dangers of the Icefall, I think most operators will say that the south side is safer and slightly more straightforward. But the real answer is no one knows what each season will bring. So train hard, gain skills on lower mountains, obtain altitude experience on another 8000m mountain before Everest, and go with a team you can count on in an emergency.

Here’s to a safe season for everyone on the Big Hill.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Follow the 2026 Everest Coverage!

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2026 podcasts on Spotify, Apple, Breaker, Pocket Casts, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

Preparing for Everest is more than Training

If you dream of climbing mountains but are unsure how to start or reach your next level, from a Colorado 14er to Rainier, Everest, or even K2, we can help. Summit Coach is a consulting service that helps aspiring climbers worldwide achieve their goals through a personalized approach based on Alan Arnette’s 30 years of high-altitude mountaineering experience and 30 years as a business executive. Please see our prices and services on the Summit Coach website.

Everest Pictures and Video

© All content and images owned and copyrighted by Alan Arnette unless noted. Unauthorized use and reproduction are strictly prohibited without specific permission.

A tour of Everest Base Camp by Alan Arnette

Alan Arnette became the oldest American to summit K2 in 2014. He has also made six expeditions to Everest or Lhotse, including a summit of Everest in 2011. He climbs to raise money and awareness of Alzheimer’s disease.

3 thoughts on “Comparing the Routes of Everest – 2026 edition”

Hi Alan when people prepare the everest summit push is it possible to follow someone\’s individual experience

I’m not sure I undertand your question, David. If yu mean on the mountian, yes, everyone except for the lead rope fixer “follows” someone else or knows what they experienced. If you mean planning for a climb back home, let’s hope they do credible research and get credible advice.

An incredible resource. The new rules on the Nepal side could decrease the numbers. Your time lines on the routes are very helpful. I have given slide shows about Sherpas and Everest about 160 times. I always referred to your posts for correct elevations and times. I no longer seek doing them but have been asked to do one several times since moving to TX 4 years ago. The University of Texas request one. I now write mysteries. Both of them reference Everest.