2022 brought even more stable weather windows than during the great Everest 2018. This May, a stalled high-pressure system made for horrendous temperatures in Northern India while paradoxically creating nearly ideal climbing conditions across much, but not all, of the Himalayas. The net result was nearly 650 people summiting from Everest’s Nepal side and another 50 on the Tibet side.

Unlike previous seasons, this spring saw more experienced climbers resulting in fewer deaths, rescues, and an overall low drama environment. Despite this good news, there were periods of brutal weather and climbing conditions, and yes, there were rescues, close-calls, and, sadly, deaths.

This season, we saw the continued trend of a very high member to support ratio. A milestone reached with more Sherpas summiting than foreigners in total since Everest climbing began in the 1920s. We’ll dig into this later. All in all, it was a year like we saw a decade ago. But, unfortunately, it was not without deaths, three deaths on Everest and three more on the other 8000ers.

In the good news department, for the first time in many years, the Nepal Ministry of Tourism seemed content to stay out of the way and the headlines. But, this spring, significant changes appeared in the world of mountaineering. These changes will disrupt decades of climbing norms on the 8000-meter peaks.

Before we get going, a note on terms. I will use the same terminology used by the Himalayan Database of members and hired. The former is also known as clients or customers, and the latter is anyone who received payment to assist members climbing the mountain, i.e., a Sherpa or Guide (foreign or domestic.) Hired, in this context, does not include other critical staff like porters, cooks, teahouse owners, or yak drivers.

Big Picture

To sum up the 2022 spring Himalayan climbing season in a phrase, it is ‘low-drama, disturbing changes.‘ In 2022, a support-to-client ratio of 1:1.7 was the highest ever on Everest. And while impossible to fully quantify; anecdotally, more climbers across all six of Nepal’s 8000ers climbed this season, and used higher flow rates of supplemental oxygen starting at lower altitudes than in history.

My early estimate for Everest summits is 240 clients supported by 399 Sherpas for 640 summits for Nepal. Add in the 50 from Tibet; 690 is on par with 2016/17. I have a very rough estimate of 200 total people on the other Nepal 8000ers. As for the member success rate on Everest, it’s around 74%, with 240 of the 325 permitted making the top.

China closed Tibet to foreigners for the third year citing COVID. As so previously, they did allow one Chinese commercial team and a second scientific team to climb. Fifty people summited, and they placed seven weather stations on Everest, including what they proudly hailed as the world’s highest at 8800 meters. They live-streamed the event to further the publicity. Not to be outdone, on May 9th, a team from National Geographic installed their station 10 meters higher on the Nepal side at a point above the Hillary Slope called Bishop’s ledge.

Who Climbed?

Nepal issued 986 permits to foreigners from 74 countries for 27 mountains. These permits generated USD$4 Million in revenue.

Just looking at Everest for 2022, as expected, there were fewer permits, 325, issued to foreigners than the record-setting 408 issued in 2021. Oddly, of the 44 teams issued permits, many were one-person teams, thus accounting for a large number of teams. Usually, there are around 30 teams on Everest. Lhotse came next with 135 permits, but many of these were people who linked Everest and Lhotse together and ‘summited’ Lhotse from the South Col at 8,000-meters.

Looking at Everest’s national distribution, the US has the largest representation with 65 members, followed by India-26, the UK-34, Nepal (non-Sherpas)-21, Canada-17, Russia-17, China-14, France-13, and Austria with 11. There were 39 countries represented by one or two climbers, which resulted in many of the country firsts that I’ll discuss later. One of the reasons for fewer climbers this year was the strict travel limitations imposed by China and the lack of sponsorship for young Indian climbers. These countries had a large presence on Everest in recent years, but not in 2022.

There were six deaths across all the peaks this spring, three on Everest, and one on Lhotse, Dhaulagiri, and Kangchenjunga:

- Pioneer Adventures, Everest May 12: Dipak Mahat got AMS while at C2, died in Kathmandu

- Seven Summits Treks, Lhotse South Face May 9: Khudam Bir Tamang, a member of Hong Sung-Taek, died from an avalanche.

- Seven Summits Club, Everest May 8: Pavel Kostrikin died at Camp 1 after getting sick at C2 on Everest from AMS

- Pioneer Adventures, Kangchenjunga May 6: Narayan Iyer 51-year-old Indian, dies from “exhaustion.”

- Seven Summits Treks, Dhaulagiri, April 11: Greek climber Antonis Sykaris is reported to have died near C3 from “exhaustion” after summiting.

- IMG, Everest, April 14: Nima Tenji Sherpa died in the Khumbu Icefall from unknown reasons, no fall, avalanche, or known illness. He was carrying loads to Camp 1.

AWOL Jetstream

2022 turned out to be an unusual weather season but in a good way. On May 5, 2022, I did a podcast with three world-class meteorologists, Michael Fagin of Everest Weather, Chris Tomer of Tomer Weather Solutions, and Marc De Keyser of Weather4expeditions, about what we were seeing and could expect these last few weeks of the season. They all agreed that it was warmer than usual, drier than expected, and with less wind. The culprit was a missing Jet Stream. It was not sitting on top of Everest like it usually does for over 48 weeks a year.

Chris Tomer went as far as saying, “We could see an unprecedented period of appropriate summit days this spring.” And, oh my, was he correct. Further, Michael Fagin predicted that the typhoon hovering in the Bay of Bengal was not going to be a threat, and he was right. Finally, Marc Dekeyser suggested that all forecasts come with a caveat but later told me, “Yep, to my experience, this will be the shortest season ever! Within a few days, the weather is becoming a bit more unsettled. Hopefully, all the people will have summited by then.”

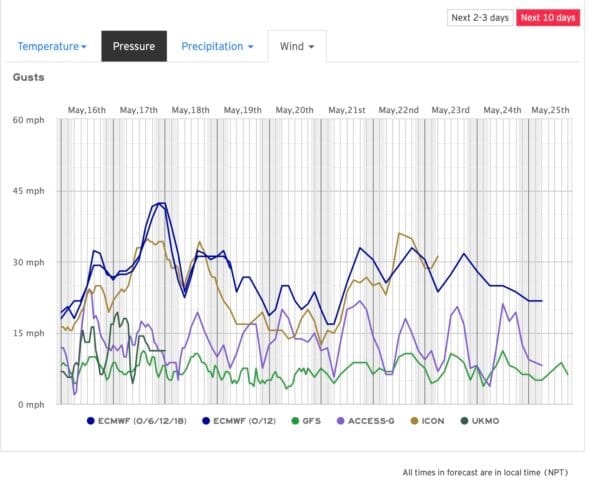

April was what we would expect, mostly clear skies, with afternoon snow showers and cold nights. However, something was different as we moved into early May, a time usually of bad weather. This wind gust model from weather.us was representative of most of May, with an occasional high period but mostly manageable winds under the 30 mph/50 kph ceiling for safety.

10 day Everest wind gust forecast courtesy of Weather.us

Summits

The Icefall Doctors got the ropes to Camp 2 right on time, but weather and logistics stalled the summit team from doing their job. Finally, the all-star Sherpa rope team got the ropes on the summit a couple of days early on May 7. Then, two days later, climbing under the public radar, Portuguese climber Pedro Queirós, 41, made the season’s first ‘member’ summit at 9:39 am on Monday, May 9, 2022, with Mingma Sherpa of 14summit. And it opened the flood gates as the winds stayed away.

For the next nine consecutive days, team after team made the trudge back to camp 2 with many members using supplemental oxygen below the traditional 7,000-meter mark. They slowly plodded up the Lhotse Face and to the South Col. One by one, they left in the dark of night, following a line of headlamps up the Triangular Face. There were a few high-wind periods, but nothing could stop the guides’ relentless pursuit of getting their clients to the summit.

- Leaving the South Col on May 11, 2022. Courtesy of Lucy Westlake and Xtreme Climbers Treks & Expeditions

2022 brought a sizeable number of summits at 690, but nowhere near the record 878 set in 2019 or close to 2016-679, 2017-692, or 2018-819. COVID and closures have taken their toll on mountaineering tourism, and that’s not all bad.

I estimate 640 from the Nepal side made up of 240 members supported by 399 Sherpas, or high-altitude workers of other ethnicities, for a support ratio of 1:1.7. As for the member success rate on Everest, its around 70%, with 240 of the 325 permitted making the top. There were 50 total summits of Chinese nationals on the Tibet side.

Stand Out Achievements

A noteworthy achievement was from the first 100% Black team, Full Circle Everest, which had all the members who attempted the summit make it with support from 10 Sherpas. They made a documentary that I’m eager to see when it comes out, probably in 2023. This is a significant accomplishment and shines a bright light on the lack of diversity in mountaineering. I explored that question with some of the team back in November when we did a Podcast.

There were a handful of individual achievements. Kami Rita Sherpa set an Everest summit record at 26 when he led the rope team on May 7. Lhakpa Sherpa, 48, set a female record with her 10th summit on May 12. Lucy Westlake, 18, set an American youngest female record on May 12. Gabby Kanizay became the youngest Australian to summit on May 14 (with her mom!). At 68 and a grandfather of five, Graham Keene became the oldest Brit.

German David Göttler, did not use supplemental oxygen and carried all of his gear – tents, sleeping bags, food, fuel, stove, etc. made the summit. He did it about as clean as one can in these modern times. He did use the ladders installed by the Icefall Doctors in the Khumbu Icefall and the Western Cwm and the fixed ropes.

Andrea Lanfri, 35, from Lucca, Italy, summited to make a point. In 2015, he contracted fulminant meningococcal septicemia that resulted in the amputation of both legs and seven fingers. Planet Mountain has a nice interview with Andrea.

There were many Lhotse summits, but most have come directly from Everest via the South Col and not from Base Camp, so I tend to notice the ones who climb in ‘style’ from a lower elevation like Camp 2 or better from base camp. Hungarian Szilárd Suhajda, who climbed independently from base camp without O’s or sherpa support and carried all his own gear made the top of Lhotse. He also has summits of K2 and Broad Peak.

A Ladies Mountain

Nepal issued 74 permits to female climbers or 22%. Female climbers represent a fast-growing segment of Everest and 8000-meter climbs. Historically, 15% of all member summits were by females. In 2019, the last ‘normal’ year, 94 summited or 23%.

This year, we saw many females not only summitting but seeking to set records for female climbers and in some cases, all-around records. A case in point is Brit, Adriana Brownlee, 21, aiming to set a record for the youngest to get all 14. She currently has four.

Canadian mountaineer Jill Wheatley summited Makalu, Kanch, and Dhaulagiri. Now she heads to Pakistan for more. Her goal is to break down the stigma associated with traumatic brain injury, vision loss, and eating disorders. She said, “Losing 70 % of my vision, I lost all depth perception. I have adapted, yet this morning as often happens, the coffee soaked my journal rather than filling my mug. There are far worse problems in our hurting world.”

A quiet Indian female climber, Baljeet Kaur, got five 8000ers this season with Peak Promotions. She summited Annapurna on April 28, Kanchenjunga on May 12, Everest then Lhotse on May 21, and Makalu on May 28, all with Mingma Sherpa.

Records

2022 may have been a record year for headlines with the word ‘record’ in it. As I said, during the season, I don’t try to follow who set what record in climbing because it’s virtually impossible to verify. Many of these are from a person who is the first from their country to the summit, and then others who have a personal story that they view as a record. Also, this year, we saw an unusual linking of multiple 8000-meter peaks. But there were a few that stand out.

Kenton Cool just got his 16th Everest summit breaking Dave Hahn’s long-standing 15. A non-Sherpa record.

An impressive and fun performance is Norwegian Kristin Harila, 36, who plans to summit all 14 peaks in six months. She already has six this season: Annapurna, Dhaulagiri, Kanchanjunga, Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu. She’ll then go for the Pakistani 8000ers after these. Pemba Sherpa, 8K Expeditions, is handling her logistics. The Sherpas supporting her, Dawa Ongju Sherpa, and Pasdawa Sherpa, have been with her on all six thus they share the same record.

Such a moment for 18-year-old American Lucy Westlake, who set an American female record. She was with Nepali outfit Xtreme Climbers’ Mingma Chhiring.

These are some of the reported but not verified, records that made headlines in the Himalayan Times:

- Sanu Sherpa makes double ascent of 13 peaks as climbers scale Makalu

- Asma Al Thani becomes first Qatari woman to scale Mt EverestAsma Al Thani becomes first Qatari woman to scale Mt Everest

- Norwegian woman, two Sherpa climbers set record scaling six 8,000ers in 29 days

- Baljeet becomes first Indian to scale 4th 8000er mountain in single season

- Himalaya Air’s Omnika Dangol becomes first Nepali cabin crew to scale Everest

- First Vietnamese woman scales Everest as Shehroze becomes youngest to climb four 8000ers

- Singer Raju Lama, Neurosurgeon Dr Ram Shrestha, among others scale Everest

- Mingma G makes it 13 with no O2 Everest summit

- South African paraglider jumps off Everest

- Kenton Cool becomes first foreigner to scale Everest 16 times

- After Annapurna, Indian climber scales Lhotse without using O2

- First Uruguayan, Emirati women among others scale Everest

- Kidney donor US army veteran sets record scaling Mt Everest

- Taiwanese woman scales Makalu completing 7 mountains above 8000m

- Indian woman scales Kanchenjunga after Annapurna

- Norwegian completes 7 summits, Quintero becomes first Honduran to scale Mt Everest

- Lucy Westlake becomes youngest American woman to scale Everest

- Black Americans create history successfully scaling Mt Everest

- Nepali woman scales Everest for record 10th time

- Norwegian woman climbs second 8,000m peak in 10 days

- Kami Rita scales Everest for 26th time as Everest summit route opens

- In historic first for Nepali Army, two personnel scale Kanchenjunga

- Raju performs solo concert on Everest

- Skalzang Rigzin becomes first Indian climber to scale Annapurna without using O2

- Taiwanese woman sets record as summit bids underway on Annapurna

And there were others:

- Manal A Rostom – 16th May (First Egyptian woman)

Seven Summits Treks touted their member’s various records:

- Nayla Nasir A. Albaloushi from the United Arab Emirates raised the flag of her country on the top of Mt. Everest 8848.86m on 14 May 2022, becoming the first-ever Emirati female to climb the world’s highest peak.

- Shehroze Kashif @thebroadboy, for your successful climb of Mt.Lhotse (4th Highest Peak) this morning 16 May 2022. With the success in Lhotse, Shehroze becomes the youngest person ever to climb four higher 8000ers (Everest, K2, Kangchenjunga, and Lhotse

- Nguyên Thi Thanh Nhā (Céline) becomes the first Vietnamese woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Céline as a member of Seven Summit Treks Everest Expedition 2022, climbs the highest mountain using the SE- Ridge (South Side) this morning at 3:30 am NPT (16 May 2022).

- Tons of congratulations to my younger brother Pasang Phurba Sherpa @pp_sherpa, who took the top of Mt. Everest 8848.86m this morning.

- ~Nayla Nasir A. Albaloushi from the United Arab Emirates stood on the top of Mt. Everest 8848.86m this morning (8 Am Nepal time – 14 May 2022) becoming the first-ever Emirati female to climb the world’s highest peak.

-

Congratulations to Antonina Samoilova -Ukraine and 14 Peaks Expedition team for your successful Mount Everest summit today morning at 6:40 am.

- Congratulations to Shehroze Kashif, for your successful climb of Mt.Lhotse this morning (16 May 2022). With the success in Lhotse, Shehroze becomes the youngest person ever to climb four higher 8000ers (Everest, K2, Kangchenjunga, and Lhotse)

Near misses

We watched several high-profile climbers this season.

Marc Batard, at age 70, wanted to make a no O’s attempt and try to validate his alternate route from the Khumbu Icefall along the flanks of Nuptse. I’ve written quite a bit about this. Once he got to Nepal, something happened to him as he started building the route. He had permit issues and some logistical snafus. But he wanted to build a Via Ferrata on the steep rock walls of Nuptse, believing it would be faster and safer, especially for the Sherpas. His vision included U-shaped metal feet and handholds that climbers would use. I can’t imagine doing this with a 50-pound load at 19,000-feet. In any event, he became disillusioned with the entire Everest scene and eventually called the whole thing off.

The South Korean Hong Sun-Taek returned for yet another attempt on the very dangerous and difficult South Face of Lhotse. He had tried in 1999, 2007, 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2019. This route is impressive as it’s reported to be the highest face of any mountain, rising 3,200-meters/10,500-feet vertically. But on May 9, a member of his support team, Khudam Bir Tamang, died from an avalanche, and the expedition ended.

Australian Ken Hutt and South African Pierre Carter wanted to paraglide off the summit, but only Pierre took flight, and it was from the South Col, not the summit.

The 8000ers

Nepal is home to eight of the highest peaks in the world. Several straddle the border with China or India. This season, In addition to Everest, five saw heavy traffic, Lhotse, Annapurna, Kangchungua, Makalu, and Dhaulagiri. Only Manaslu and Cho Oyu were quiet. Some teams made it look easy, while others made strange mistakes, and then you had cases, most unreported or called-out, of unconventional climbing techniques. However, well over 200 people will return home with claims of one, two, or more 8000-meter summits this spring.

This is a very rough estimate of the summits on Nepal’s 8000ers:

- Lhotse: 135 member permits with 13 summits supported by 14 7Sherpas (way off when the Everest-Lhotse link is counted)

- Annapurna: 26 member permits with 7 summits supported by 14 Sherpas

- Kangchungua: 69 member permits with 24 summits supported by 38 Sherpas

- Makalu: 50 member permits with 14 summits supported by 13 Sherpas

- Dhaulagiri: 27 member permits with 15 summits supported by 17 Sherpas

The 8000er season kicked off with Mingma G’ Imagine Nepal team summitting Dhaulagiri, the world’s 7th highest peak at 8,167 m (26,795 ft) on April 9, 2022, at 10:30 am by 10 members supported by 12 Sherpas. Next up was Annapurna with summits by Pemba Sherpa of 8K Expeditions of four members supported by seven Sherpas.

By far, the most active peak was Kanch. Nepal issued 68 permits to foreigners for Kanchenjunga, 8586-meters, this spring and on May 5, 2022, at least 30 stood on the summit. Multiple people summited several 8000ers. The most popular combination was Annapurna and Kanchenjunga, but Kristin Harila. got six of Nepal’s 8000ers, and Indian Baljeet Kuir linked Everest with Lhotse two weeks after summiting Annapurna and Kanch. Again, using the new formula, the ‘overwhelming’ the mountain formal proved the best way to plow the route for the members.

Over on Dhaulagiri, where 83-year-old Spaniard Carlos Soria Fontán, threw in the towel for the 13th time. His small team got a quick start after acclimatizing in the Khumbu and reached Camp 3 before the weather closed in, forcing them to retreat. They made another attempt but stopped short and eventually ended the effort. Carlos says he’ll be back for his 14th attempt having on Dhaulagiri and Shishapangma left to complete his 8000ers quest.

One of the big ones and a true record was on Makalu by Adrian Ballinger, co-founder of Alpenglow. He skied from just slightly below the summit to base camp. Others have skied Makalu, but most started at 7000 or 7500-meters on the 8495-meter peak. Adrian texted me, “I summited today with Dorji Sonam and Pasang Sona (Alpenglow Sherpa). We fixed to the summit from where rope fixing ended by French couloir. And….I skied Makalu!!!!!! I just got back to ABC. First on top for season. Alpenglow pride” Please see the Podcast interview I did with Adrian just as he got home in late May 2022.

Also notable on Makalu was Adrian Ballinger’s Alpenglow team Karl Egloff and Nico Miranda set an FNT-Fastest Known Time record reaching the summit of Makalu in 17 hours and 18 minutes, not using supplemental oxygen.

Another moment was when Tim Bogdanov, 37, narrowly avoided death o Annapurna last month. I also dia Podcast with him on his experience.

Changes

Mountaineering is changing. Supporters of the changes call it an improvement, evolution, and increasing access to more people. Critics call it crowding, cheating, disrespectful and shameful. No matter, it’s changing, and we never saw more evidence than across Nepals’ 8000-meters peaks this Spring.

Before I break down what I see as the significant changes, I want to be clear that my comments are not a huge blanket saying every climber and every team is changing equally; in fact, some are not. My good friend Phil Crampon of Altitude Junkies shows his preferences with his usual diplomacy:

We are now back in Kathmandu, flying directly from base camp, 28 days after leaving this wonderful city. We reached the summit safely without any cheesy gimmicks, such as at home hypoxic tents and we did not have a single Instagram influencer on the team. We resembled old school climbers, getting shit done without all the hype. We were the first team on top on the 12th and nobody else was near us all day until we descended and met ascending climbers later in the day. We had the summit to ourselves for the second year in a row.

Some of our climbers will depart for home tomorrow. As always, the summit would not be possible without the fantastic Sherpa staff on the hill and in the kitchen. We are already looking forward to next years expedition to the “Big E”.

Three Commercial Pillars

Commercial mountaineering has three pillars: Sherpa support, Western guide support, and oxygen use. These have always been a mainstay for Everest climbs, but the amount and roles have drastically changed over the past 30-years.

The pre-1990s expeditions, mostly National Teams, hired Sherpas primarily as load carriers, with some famous exceptions like Tenzing Norgay. The members fixed the ropes, established camps, and led the climbing team, almost always members, to the summit.

When commercialization took off in the early 1990’s companies like Adventure Consultants and Mountain Madness catered to non-professional climbers. They expanded the Sherpa role to carry the group and personal loads. Over time, the strong but relatively inexperienced Sherpas began to manage the route with fixed ropes and establish high camps. After a few years, the Sherpas escorted members from the base camp to the summit. During this period, supplemental oxygen technology improved, making higher flow rates possible, and enabling perhaps, weaker members to summit.

As we entered the early 2010s, many Sherpas had 10, 15, or even 20 Everest summits, plus experience on the other 8000ers. They saw an opportunity to cut out the western operator and guide members themselves for half of the $65,000 price usually charged. Initially, they focused on Everest catering to the Chinese and Indian emerging middle-class. They enjoyed great success. By the later 2010’s they had captured 80% of the commercial business on Everest and expanded to K2, then to all of the 8000-meter peaks across Pakistan, Tibet, and Nepal. Some swept in the Seven Summits and Polar expeditions to their menu of adventures.

As we saw in the Spring of 2022, across five 8000-meter peaks, several large Sherpa-owned companies honed their now proven technique by having a team of six to eight strong Sherpas break trail and install the fixed-line from base camp to the summit following well-known and proven routes. They established high camps with tents, fuel and stoves, and oxygen and sometimes even carried the member’s sleeping bags, pads, and food.

Once the route was set to the summit, the members would arrive. Some only a few days earlier to base camp after acclimatizing at home or elsewhere in the mountains. With all the hard work completed, the members clipped into the fixed-line and followed the Sherpas on the boot path to the top. They climbed on more efficient oxygen delivery systems at higher flow rates than in previous generations. With this formula this season, the ‘other’ 8000ers saw many summits, and the number of doubles, triples, and a few five’s and six’s take off in 2022. It was a banner year for climbers using this formula, and this will be the new commercial normal in climbing all 8000-meter peaks.

Of course, not every climber follows this program, and others climb “independently.” However, they definitely benefited from the fixed ropes and boot path and, in some cases, support from Sherpas on other teams when there was trouble.

Now, please don’t get me wrong. Even though this new formula is distasteful to many old-timers, purists, armchair climbers, and journalists, it’s the style of today’s high-altitude climbing for the vast majority of climbers. But moreover, it’s opening the market to hundreds who otherwise would not have the opportunity. So while those who summited have critics, I’m happy for them. But it is not the way mountains were climbed in the past.

Two Climber Types, Two Summits

I believe the alpine climbing community (not rock, ice or hikers, or trekkers) has split into two groups with different standards. The first category is what I’ll call ‘recreational’ climbers, and I would put myself into that group. The other group is “record-seeking” climbers. Those would include anyone purposefully attempting to set a record – speed, age, unclimbed, new route, etc.

While I believe style applies to both groups, the latter should be held to a higher standard. Those who use the recreational approach and claim a record deserve a high level of scrutiny, even though their feat might have been a fantastic display of strength, determination, and even skill.

In other words, suppose you climb one 8000er, or 14, using a standard route, following a path carved out by super-strong support, and you use supplemental oxygen at a high flow rate and summit. Then you claim you set a new record. Was your style different than the climber who set that same record ten or twenty years earlier?

Comparisons may not be equivalent, so the differences need to be pointed out to the admiring public, who may not be aware of such nuances. However, climbing is not the Olympics or even a sport with rules. It’s only a sport that depends on personal integrity to claim an accomplishment legitimately. And it takes an ugly turn when someone claims a record, compares themselves to a previous record when entirely different styles were used, and there is no acknowledgment of the difference.

As we saw last autumn on Manaslu, there has been a fraud of sorts. People like me believed they had made the true summit of Manaslu, even being told by long-time Sherpa guides that they had. However, an accidental drone video revealed the actual top was achievable, something already known but ignored for years. The reason for this eludes me a bit, but it has to do with safety and achievability in the eyes of the climbing Sherpas, I believe. However, I think reaching the true summit is well beyond the safety and risk limits of most reputable guides. But, the fact remained that for many, they had reached the fore-summit. A similar story is told for Broad Peak, Makalu, Shishapangma, Nuptse, and countless other dangerous and difficult mountains. So in a sport with no rules, it comes down to personal integrity.

On April 30, 2013, Rock & Ice magazine published my article, “Everest Deserves Respect.” My argument was that climbing Everest was hard, damn hard. That it’s not a ‘cake-walk.’ Anyone who tries it deserves respect. Also, every climber needs to respect all mountains by leaving no evidence of their climb, honoring the local people. Respect the people who help them climb—and show humility and gratitude for the opportunity. Well, some people lost these attributes in 2022.

Soul Trouble

In today’s climbing world, selfie after selfie shows mug shots of climbers on the summit, oxygen masks hidden away. They show ‘art’ at base camp with the ‘climber’ doing yoga or runway fashion-model poses. They talk about how great they did and often don’t mention the team they were on or, unforgivably, the names of the Sherpas who got them up and back down. In other words, it was all about them.

Some fail miserably to understand the deeper meaning of climbing and the significance of summiting a Mount Everest, Makalu, Kanch, or any mountain for that fact. Instead, it was about getting a trophy, in a sport where everyone gets a trophy these days, even if they don’t summit.

Sadly, some in the sport have turned it into a way of selling books, documentaries, t-shirts, and sponsors for their next climb. And their souls. A few years ago, I attended a presentation by a well-known financial advisor. He talked proudly about his Everest summit. Then he went on to say he had summited K2 when in fact, he left base camp soon after arriving due to legitimate family issues. Why did he feel the need to outright lie? This erosion is not limited to the clients. Some operators have taken center stage to enable this behavior and, in some cases, serve as role models and enablers of what not to do.

Style Matters

Again well done to those who did summit, but we need to look deeper into style. By that, I mean what most veteran climbers call “fair means.” Use of oxygen starting at what camp? Level of support to break trail? Use of helicopters to shortcut treks to base camp. Did they reach the true summit or a false one? All of these are fair questions in my mind. And, to be clear, they don’t invalidate a genuine summit but only put the achievement into perspective, especially if the climber claims a ‘record.’ Many of these claims are solid, and the individual deserves the praise they receive back home.

However, I worry about the soul of the sport with the extensive use of helicopters, oxygen, and Sherpa support. People are now buying a summit, not earning it. Yes, there are more summits, lower death rates, and faster climbs, but is this the way to play the sport?

Helicopters

Helicopters are now used the same way trails, and yaks were a decade ago. Some Nepali companies own their own chopper and offer it as part of their higher-end packages. Heli’s are not new to Nepal, Everest, or mountaineering. The U.S. National Park Service has one on stand-by for medical evacuations on Denali. Same for Aconcagua, and it also hauls away trash for the high camps. But in Nepal, they have taken this valuable tool and used it as a marketing tool, or worse, a crutch.

Once the Everest climbers finish their acclimatization rotations complete, many take a helicopter and fly to Namche, Lukla, or even Kathmandu for a ‘vacation’ from the trials of climbing Everest. As I’ve mentioned many times, the late legend Anatoli Boukreev spoke of ‘touching grass’ before the summit attempt. However, in contrast to today, Antoli meant taking a short walk to treeline and staying in a teahouse, not flying to a five-star hotel in Kathmandu.

Over the past few years, climber after climber has noted that Everest base Camp has turned into an airport with nonstop helicopter takeoffs and landings. Some are medical emergencies, but most are for ‘climbers with means’ to bypass the inconvenience of spending time at base camp. Some guides will use these flights to ferry fresh meat or delicacies from Kathmandu to nourish their clients at base camp.

The locals who live year-round in villages like Pangchboche, Periche, or Dingboche comment that the constant helicopter flights create unbearable noise pollution in an otherwise pristine environment. They note that it has become routine for the rich to hike to Kalapathar and then take a chopper from Gorak Shep or Lobuche back to Kathmandu. They complain to local authorities, but to no avail.

On the 8000ers this year, we saw many, many climbers fly from one base camp to another. For convenience? To save energy for their next climb? When the forecasts called for poor weather, some members flew back to Kathmandu rather than stick it out in base camp. Some even did this when there were delays in getting the ropes to the summit. I don’t think those who climbed these peaks before them a decade ago did this. Times are a changing. I get it, like pre-acclimatization at home or using supplemental oxygen at eight liters per minute is the way the ‘cool kids’ climb today. But come-on man, Is this really how to do it?

On Everest, there are valid reports of climbers who skipped all rotations and were flown by helicopter to and from Camp 2. They then went on to ‘summit’ using massive amounts of supplemental oxygen. One case mentioned to me said the person used 14 bottles. The Nepal Ministry of Tourism explicitly says helicopters are only used above EBC for medical evacuations and to ferry gear to fix the rope to the summit, thus reducing the number of trips through the Icefall for the sherpas. They say no member should ever be flown above base camp to minimize the climb.

I was asked if someone could summit without acclimatizing; well, I guess this is how a person could do it, but really?

As I’ve said before, helicopters have a place and time in the mountains. They’ve been used in the European Alps for decades to save lives. The Nepal Government, acting on behalf of the safety of the Sherpas, now allows helicopters to fly to Camp 2 to ferry ropes and gear to fix the line to the summit, including Italian Alpinist and helicopter pilot Simone Morro plus choppers from Seven Summits Treks. This is tremendous because it limits scores of trips through the Icefall by Sherpas and reduces their overall risks.

After dropping off the gear, trash was loaded from the area and flown back down valley for proper disposal. Unfortunately, after the 2015 earthquake hit, many teams were forced to abandon tents and gear at Camps 1 and 2. With people needing to hustle to get flown out so the helicopters could be used elsewhere in Nepal, the camps 2 became very littered. Since then, there have been multiple clean-up efforts, but we saw a more coordinated effort this year. Thanks to all.

Oxygen

There were several case studies on the use of supplemental oxygen and style. I’ve written ad nauseam about why oxygen keeps you warmer and alive and that only 3% of Everest climbers shun it. A growing trend has been for operators to ‘aid’ their climbers with higher flow rates starting at lower elevations. The historical standard was to acclimatize by sleeping at Camp 3 after a few rotations, then waiting for the weather window before returning to Camp 3 where you slept on half a liter per minute (lpm) of supplemental oxygen and continued to use it at flow rates for two to four lpm to the summit and back to the South Col.

Today, many operators skip the C3 rotation and maybe tag 7,000-meters on the Lhotse Face. Then, when the weather window appears, they return to Camp 2 and begin their summit push to C3, the South Col, and higher, all while using oxygen. In other words, their clients use oxygen at an elevation lower than Aconcagua.

Some operators like Furtenbach Adventures have modified regulators that allow 8 lpm flow rates, as Lukas says, “but only on technical sections at higher altitudes so as to avoid bottlenecks.” That said, his 17 members, supported by 27 Sherpas summited after leaving their homes only 16 days earlier. They also used hypoxic tents to ‘pre-acclimatize before leaving home. Times are a changing.

But it’s a point of style and pride for those who don’t want to use it. However, when they face death, they have a choice, use it, turn around, or push to their potential death. Carla Perez on Makalu began to feel the usual symptoms of a no Os climb with cold extremities, shivering, and generally not well. She had a choice. In her own words:

And well back from my last rotation that became the last rotation + summit attempt, because apparently May 12 was a good day to try to go to the summit.

I spent 8 days through the high altitudes moving between field and field and resting on C1, almost transformed into Yeti. I arrived very close to the top but the wind and cold went on so much before dawn, that I moved while continuing to shiver from the cold and with numb hands and feet, I saw no choice but to turn around 200 meters from the summit to avoid consequences, that is, around 8250 meters. Those who tried “without O2” put oxygen and there were still people with frostbite, my team that was going that day proposed me to do the same but it did not motivate me, I remained faithful to my plan to try without the help of O2. Carla said to myself: Why would you propose these challenges to yourself, if given the moment, you look for it easily and guaranteed? So I turned around, just like two Italian friends who were without a mask. Now days off, cure the crumbs and plan one more attempt😉😊🤫🤓🙌🏼… #liveyouradventure @eddiebauer #womenarenotsmallmen

She returned to Makalu and summited on May 25, without supplemental oxygen.

And my friend Wilco van Rooijen on Kangchenjunga faced a similar dilemma

Where to start the story? So much has happened. Cas stayed behind which made it mentally hard. Only 1 climber summited in 20 hours. Using oxygen, it takes 12 hours. But me and extra oxygen? Do I have a choice? Do I stick to my principles, or do I adapt to the new situation? Then Lolo invited me to come along with him and his Sherpa. He is using extra oxygen, so I do too. The first time in my life! I have 2 bottles of oxygen, but I don’t have a Sherpa to assist me in carrying them so the extra 6 kgs are on my back. If the weather stays, I have a chance. But then, at 8,100 meters Lolo’s Sherpa encounters a problem: pain in his feet due to his boots. Lolo decides to go back with him. Decision time again… Do I continue? Do I have enough oxygen? It’s more than 500 meters, long way up and back down again. What if my oxygen runs out? Hallucinations, black fingers? Do I really want to be dependent on this?

I see the row of 18 climbers – all with extra oxygen and Sherpas to help carry. No, this is not our way and what we believe. No summit is worth it. I quit! So, I returned with Lolo and his brave Sherpa. Supplementary oxygen was once but never again. I don’t like my life depending on a technical system. It took an adventure to realize how important it is to keep faith in your beliefs instead of going for a ‘quick’ success. And that’s why I love the mountains, the lessons you learn time and time again!

He made another attempt with the same result, saying that he chose style over a summit. And Billi Bierling on Dhaulagiri also climbing without Os, carrying her own gear, found herself in trouble as she told excellent mountaineering journalist Stefan Nestler:

“It was very strenuous because I was climbing without bottled oxygen and carried my own gear in my backpack. The Northeast Ridge is just mercilessly steep.” She arrived hours later than her team to Camp 3. “Two hours was not enough time for me to recover. If I had attempted the summit, I might have made it to the top, but might have gotten into trouble on the descent. I didn’t want to put anyone through that. I was aware that the summit was only half the way. The mountain is out of my league, but I’m very grateful to have come this far under the difficult conditions.”

Stefan sums it up nicely, “Some high-altitude climbers could take a leaf out of that kind of honesty and humility.”

Sherpa support

With 640 Nepal side summits broken down as 240 members with 399 Sherpas, high-altitude workers, aka Sherpas, and the many other ethnicities who work on Everest now surpass foreigners with the largest number of all-time summits. From 1953 to 2021, the Himalayan Database shows that 5,351 members and 5,305 Sherpas summited; now, it’s 5591 to 5704.

Some large teams had a mind-boggling member-to-support ratio, some as high as two and a half hired for every member. They had 130 members supported by 194 hired for these ten teams, a ratio of 1.5 hired for every member. A lot of this has to do with carrying extra oxygen. More on this later.

- Elite Expeditions: 16 members with 38 hired – 1:2.37

- Asian Trekking: 6 members with 17 hired – 1: 2.8

- Furtenbach Adventures: 17 members with 27 hired – 1:2.25

- Climbing the Seven Summits: 12 members with 19 hired – 1:1.6

- Imagine Nepal: 11 members with 16 hired – 1:1.45

- 8kexpeditions: 18 members with 24 hired – 1:1.3

- Madison Mountaineering: 12 members with 15 hired – 1:1.25

- 7 Summits Club: 13 members with 15 hired – 1:1.15

- Seven Summits Treks: 25 members with 25 hired – 1:1

When I asked Lukas Furtenbach about his large support to member ratio, he sharply defended his approach:

For our standard Flash clients we have 2 sherpa for each client. but not to carry them up. only one Sherpa is climbing with each client. the extra Sherpas are carrying the extra oxygen and redundant o2 systems and are there for rescues in emergency situations. in our summit night 12/13 may for example we could have climbed c4 to summit in 4-6 hours easily with out clients. but we were blocked by two very slow teams that did not let anyone pass. so it took us 11 hours up and down also delayed, and we were standing around waiting in traffic for hours. if in such a situation, you don’t have enough spare o2, you either have to turn your clients around, or they run out of o2 and die. I saw many clients and sherpas from other teams running out of o2 that night and day (and I saw sherpas carrying 25kg backpacks to c4 without o2).

He’s not the only one. While I understand this model, it does explain the long lines of headlamps we see in the pictures. So the next time an Everest climber complains about crowds, perhaps they should look at how much support they require.

Summary

First, my sincere congratulations to all who went to Everest and the other peaks this 2022 spring season. Also, well done to the Icefall Doctors, Sherpas, porters, cooks, assistants, Sherpas, guides, teahouse owners, yak herders – everyone. It takes a team to pull this off year after year.

The weather cooperated for most of this year, allowing infrequent queuing in the usual places. A few teams hit poor weather patches, but the 70% summit rate for members is the tale of the tape and says it was a pretty good season.

Also, sadly the death rate is an indicator of safety and success each year. This season the Everest summit death rate was a very low 0.42%, the second-lowest next to the 0.23% in 2008. On the rest of the 8000ers, there were one or no deaths. This is a tribute to the Sherpas, guides, and members who came prepared with the proper experience to earn the right to summit Everest. Oh, and the weather helped immensely.

The season is over, and some move to Pakistan for their summer 8000er season. I hear that K2 will be crowded. That makes me sad because it’s in an entirely different league than the Nepal 8000ers, and it’s a place you should not be taken lightly or assume you can learn the fly.

Yes, mountaineering is changing. Change is inevitable and cannot be stopped. What can be changed is how each of us approaches this sport. Every attempt, every summit is a testament to those who summited before us. We owe them respect and honor. We need to understand their methods and acknowledge their achievements.

No one climbs a mountain alone. Even Messner had a cook.

Climb On!

Alan

Memories are Everything

Here’s the video podcast version of this Season Summary:

The Podcast on alanarnette.com

You can listen to #everest2022 podcasts on Spotify, Apple Podcast, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts, RadioPublic, Anchor, and more. Just search for “alan arnette” on your favorite podcast platform.

The Himalayan Database Needs Your Help

If you climbed this spring 2022 season and hadn’t already registered with the HDB, please use this QR code to register so your climb can be counted.

Why this coverage?

I’m just one guy who loves climbing. With 35 serious climbing expeditions, including four Everest trips under my belt and a summit in 2011, I use my site to share those experiences, demystify Everest each year and bring awareness to Alzheimer’s Disease. My mom, Ida Arnette, died from this disease in 2009, as have four of my aunts. It was a heartbreaking experience that I never want anyone to go through, so I ask for donations to non-profits where 100% goes to them and nothing ever to me.![]()

- Ida Arnette 1926-2009

Previous Everest 2022 Season Coverage Posts

- Everest 2022: Welcome to Everest 2022 Coverage

- Everest 2022: Climbers Leave for Nepal

- Everest 2022: Icefall Doctors leave for EBC and Ukraine Guide Bans Russians

- Everest 2022: A look at This Spring’s 8000ers

- Everest 2022: Leaving Nothing Unsaid

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update March 27 – And We’re Off!

- Everest 2022: Climbers to Watch – Updated

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update April 3 – Trekking

- Everest 2022: The Moments I First Considered Climbing Everest, and Your’s?

- Everest 2022: Interview with Garrett Madison from Namche Bazaar

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update April 10 – First 8000er Summits

- Everest 2022: First Death on an 8000er this season – Update

- Everest 2022: Teams Arrive at Everest Base Camp

- Everest 2022: Sherpa Death on Everest

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update April 17 – First Deaths, Carlos on his Way!

- Everest 2022: A Solemn Day of Remembrance on Everest

- Everest 2022: How Fast Can You Climb Everest?

- Everest 2022: Teams in Tibet?

- Everest 2022: Climbers Begin Rotations and Into the Icefall

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update April 24 – First Rotations Begin

- Everest 2022: When Will They Summit?

- Everest 2022: Acclimatization Protocol

- Everest 2022: 8000er Summits!

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update May 1 – Summits, Rescues, and Climbing – A ‘Normal’ Season

- Everest 2022: First Everest Summits of the year – Confirmed

- Everest 2022: Chinese Weather Station

- Everest 2022: World’s Third Highest Peak, Kangchenjunga, Sees Multiple Summits

- Everest 2022: Talking Weather with Three Experts

- Everest 2022: 3rd Death of Season

- Everest 2022: Another Death on the 8000ers.

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update May 8 – Ropes to the Summit!

- Everest 2022: Alpenglow Makalu Success, Avalanche Death on Lhotse

- Rescue and Frostbite on Annapurna 2022: Tim Bogdanov

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 1 Underway

- Everest 2022: First Member Summit was Yesterday, May 9!

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 2 Recap – 100+ Summits, 1 Death

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 3 – Update 1

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 3 Recap

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 4 – Update

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 4 – Recap

- Special Podcast: Chatting With Jim Davidson about Everest Summits

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 5 – Update 3

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update May 15 – Summits, Summits, Summits in Great Weather

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 6 – Recap

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 7 – Recap

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 8 Recap

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 9

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 9 – Recap

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 10 – Recap

- Everest 2022: Weekend Update May 22 – The Season That Won’t End

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 11 – Recap

- Video Interview Adrian Ballinger, Alpenglow, on his Makalu Record Ski Descent

- Everest 2022: Summit Wave 12 – Recap

- Everest 2022 Season Summary: The Year of the Missing Jetstream

2 thoughts on “Everest 2022 Season Summary: The Year of the Missing Jetstream”

Thanks very much Alan. Your core statement is „…next time when you wonder about a jam on the hill, think about how much support you just need to try to make it to the top.“ Nothing to add in this regard.

Even if strategies progress, does it really mean it’s the right approach? The right style? The right ethics? People who climb Everest less than 20 days after having left home miss an important point: the dignity and respect the mountain deserves. They tick a box and move on to whatever their next project is.

Nothing to do with climbing, just pathetic endeavors.

Thank you so much for your coverage of the 2022 climbing spring season on Everest. I respect your honesty and candid comments. I trekked to Everest base camp in May 2011 and for me it is and always will be my trip of my lifetime!

NAMASTE

Comments are closed.